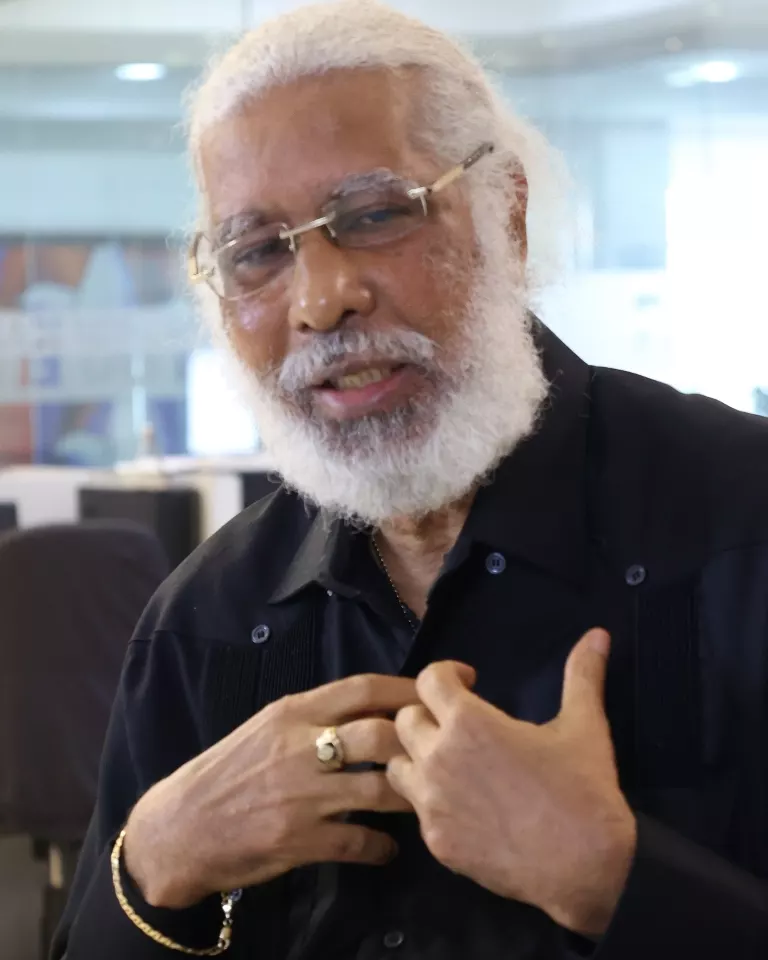

HOLY SUNDAY.-The life story of Juan Hubieres is a mixture that is difficult to imagine with just a look at the profile of today’s politician, businessman and union leader.

In his early years, Hubieres worked in agriculture, was a salesman, was a wrestler, a chess player, and a newspaper seller.

His connections with transportation came after renting a bus with his family that, initially, did nothing but give him problems; and he combined all of this with social movements and the rebellion typical of an era that, for Juan, came with the factory.

The beginnings

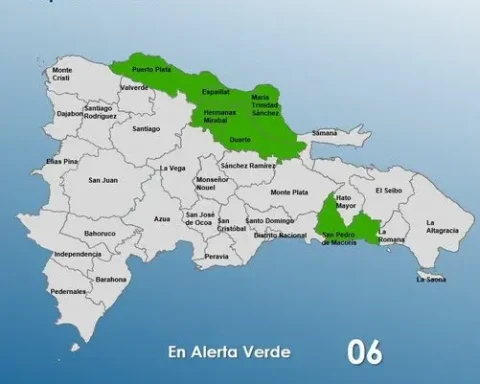

He was born in 1955 in Bayaguana, Monte Plata—then under the jurisdiction of San Cristóbal—into a peasant family marked by hard work and self-sufficiency.

His mother, Catalina de Rosario, and his father, the farmer Juan Antonio Hubieres, saw him leave very soon into the arms of his grandparents.

“That belly is male, and it’s mine,” she remembers her grandfather, Rafael Hubieres, saying when he found out about the pregnancy. But it was María Aquino Mejía, his grandmother, who ended up raising him: “My grandmother… didn’t give me away, but rather took charge.”

At three years old, after a strong wind that the family read as a “sign,” the grandmother moved with the child to the town.

There, amid precariousness, she set up a subsistence venture: she exchanged bunches of bananas for money or groceries, roasted coffee, made gofio and survived with the ingenuity of someone who knows scarcity. From her, Hubieres learned the economy of necessity and barter, as well as a practical sense that would mark his entire life.

From the age of seven, Juan knew the street as a work space.

He traveled on foot, by donkey or bus, and turned any opportunity into a small business.

He collected cashews, his grandmother made the candy, and he sold it on the busiest dates in Bayaguana—the “first Fridays” and the Sundays of pilgrimage to Santo Cristo.

He also washed and refilled bottles to sell “bottle for holy water, at a lot,” meeting a devotional demand that turned faith into cash flow. He became a shoeshine boy: “Brown and black, for five shillings you can get a new one,” he shouted, before assembling his own bench and toolbox.

Later he was a paletero. The pattern was always the same: look at the context, detect the need, solve it.

He planted cassava, sweet potato and rice; He learned to cut down mountains, to set fire to the brush, to plow with a hoe and to open furrows on impossible hills. From his father he inherited the discipline of the countryside – “working on the land is from dawn to dusk” – and respect for the harshness of the peasant’s day. Over the years, those scenes of machete and callo coexist in his memory with the domestic epic of his grandmother’s ventorrillo.

rebel connection

At the age of fourteen he came across an improvised ring in the town. The wrestling fever—“vampire, chaos, puma”—had caught on in the youth of the time and a neighbor set up a ring for the neighborhood challengers. Social groups linked to the Dominican Popular Movement saw him fight and recruited him with a phrase that he reproduces with a smile: “Do you want to fight? Come fight for real.”

He became a voracious reader. He helped found the Flavio Suero Student Front (FEFLAS) under the umbrella of the MPD, setting up neighborhood committees and coordinating strikes in Bayaguana, which became — he says — “the second San Francisco de Macorís” due to the intensity of its protests.

His university journey took him to the UASD. First he enrolled in Pedagogy; Then, seduced by a poster and a talk, he switched to Cinema at the School of Arts.

With that base, he began to produce and sell posters in Bayaguana: he designed, framed and framed; a small creative and commercial circuit that supported his studies. Afterwards, his academic career continued at the UCE, where he taught Sociology and History for years.

Before establishing himself as a teacher, he managed three nightclubs: “I got into that world, a world upside down,” he remembers. He then made a decision that is seen as a turning point: he sold everything and returned to focusing on studying.

Intimately, he defines himself as a believer (“I go to mass when I can and when I want”) and claims an original rebellion: “I was born a rebel.” He does not display it as a romantic gesture, but as a method of life: breaking the scab, like a seed that sprouts.

Self-perception

— Support to sectors

Hubieres places himself on the side of the informal jobs, the unrewarded workers, the people who support the city at dawn. Maybe because he also did it: sell clothes and shoes at the flea market.