He has just turned 70 and is celebrating it in the best way he can: exposing the result of the last few months of work, which, in many ways, have been feverish. The title of the show recycled papers, speaks clearly of the purpose of restoring utility —which is like saying life— to matter that, after having served us, we throw away without further consideration.

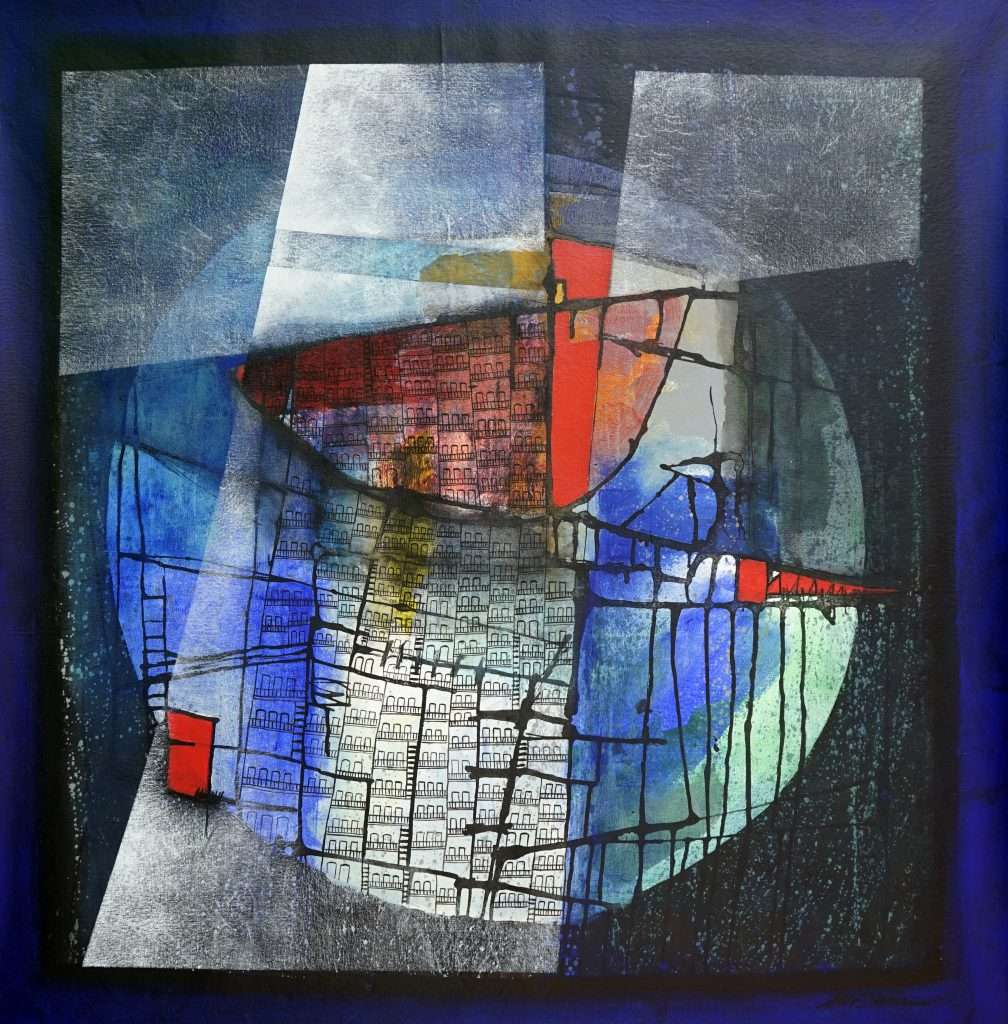

They are pictorial works on recycled paper through a complex craft process. In two words, José Omar has manufactured the support for these new pieces, which continue to express the real and dreamed city, from the angles that the creative emotion dictates to the laborious hand.

He has behind him more than thirty-five personal exhibitions held in Cuba, Mexico, Colombia, Honduras, the United States, Panama and Sweden; and about three hundred collectives. He has taught engraving, drawing and painting at different levels of education. More than all that, he is an active creator with fifty years of professional work in the field of art.

Let’s go to the dialogue.

Tell us about your origins.

I had the privilege of being born in the province of Matanzas, on February 1, 1953. We were two children of a love marriage: my brother —a journalist, who died in 2017— and I, who turned out to be an artist.

I heard that your father was also an artist.

His name was Daniel Torres Font. He studied at the San Alejandro Academy of Fine Arts. He was a fellow student of Carmelo González, Servando Cabrera and other important figures of the national plastic arts. When he graduated, he went to his home province, but found no steady job. He made drawings for the press, advertisements and everything possible to support the family. In 1956 he applied to CMQ TV and achieved the position of set painter in the department headed by Luis Márquez, a prominent set designer. That is why the family moves to Havana.

My father abandons painting. The scenery was not like now; He would go to studios in the morning, rehearse at 1 in the afternoon and stand guard at night in case something happened with the work done, which sometimes happened. His world became television. There he gained great professional prestige. Andy, the painter, can attest to that, as can Nieves Laferté, the brilliant costume designer.

It was in the 80’s that he resumed painting. He had great technical mastery and an extraordinary drawing; Furthermore, he was a voracious reader. I think I inherited his sense of color and passion for poetry.

He died in October 1989. In 1991 I organized a show for him at Galería 23 y 12. When my brother decided to live outside of Cuba, he chose a group of his pieces, which are still family heritage. I keep others.

Do you plan to promote a retrospective with that?

I don’t think it’s enough for a retrospective of his work; but it is possible to think of an exhibition with the two sets that will update the knowledge of their artistic work a little among the youngest.

Where did you study?

In 1968 I took the tests at the National School of Art (ENA). My father prepared me a few days before in drawing from life. In the end they pass me and I graduate in 1973.

It was a wonderful group. Among my classmates were Flavio Garciandía, Rogelio López Marín (Gory) and Cosme Proenza.

At the ENA I discovered engraving, which has been my passion ever since. The link is given through Luis Miguel Valdés, my teacher, who instilled in me a love for that discipline or genre. It was the only subject in which I got 100 points in my entire student life.

Luis Miguel took me to the Experimental Graphics Workshop in Havana (TEGH) when he was still a senior. There I printed my first pieces; among them the series Revolution is to build, which was mentioned in the Salón 26 de julio de las FAR. On that occasion, José Gómez Fresquet (Frémez) was awarded.

Days before, I married Vivian, my wife of a lifetime. The prize consisted of a month in a tourist center with a companion and expenses paid. I couldn’t miss the opportunity: our honeymoon was free… I’m talking about December 1973.

Tell us about your relationship with the TEGH.

The workshop was my home from 1972 until recently.

I really graduated from painting, but I didn’t have space to paint, and the workshop was the solution for many. There I was lucky enough to meet artists like Umberto Peña, Sosabravo, Posada, Contino and Frémez, who were already established, and young masters like Luis Miguel, Nelson Domínguez, Fabelo and Roger Aguilar, among others.

In 1990 he was part of the Technical Advisory Council of the TEGH. Paneca, director at the time, was leaving for Venezuela; other artists also left the country. It was Special Period. In a meeting they asked who would stay in Cuba, and they all looked at me. My stage as director of the workshop began, which lasted twelve years, until 2002.

In the midst of the great limitations of that time, I created the National Collection stamp. It allowed me to commission artists for a 50/50 edition. I’m talking about Fabelo, Kcho, Pedro Pablo Oliva…; Of the 50% that was owned by the workshop, he sold half in foreign currency, and already paid for the edition; the other half was sold in pesos, to promote collecting in the country, which had plummeted.

I also made a commercial gallery inside the workshop. The works were sold in pesos, at affordable prices. And it promoted the sale to the population on designated dates such as Father’s Day, Valentine’s Day, Mother’s Day…

I remember. Around that time I acquired some valuable pieces.

I was always interested in the multiple original reaching the population. It was a personal concern that I took to a Uneac Congress, in which I received support. But in our battered economy everything goes wrong. When, due to illness and work exhaustion, I decided to seclude myself at home to paint, my succeeding colleagues did little to consolidate and advance those ideas.

Are there recurring themes in your work?

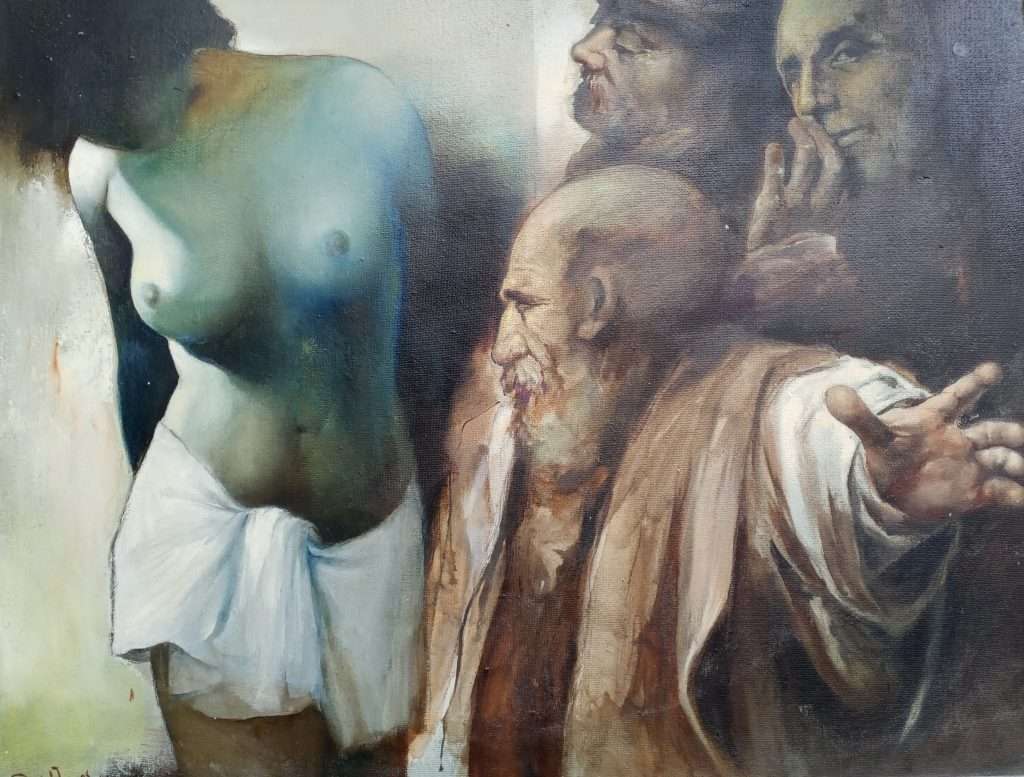

The city, its architecture, the texture and color of the houses and walls. Through the contemplation of the city my vision of the world, of society, is expressed. It is a hedonistic work, I do not deny it. I am a lover of poetry, and I have had and still have several poet friends: César López, Pablo Armando Fernández, Pausides and Waldo Leyva, who is like my brother. My work has always had to do with poetry.

What has been your most important personal sample?

I don’t think I can point to just one. In 2005 I made Variations in sepia, at the Rum Museum. In 2014 I exhibited paintings in Collage Havana. from 2017 is recycled versions, intervened engravings, in the Graphics Workshop. And from 2022 it is memory of a time, exhibited in the Villa Manuela Gallery.

These samples mark different chores, guidelines in my work, and through them you can follow the development of a personal poetics. The first was cured by David Mateo; the others, by Marilyn Sampera and Virginia Alberdi, all excellent professionals.

Lately you make your own paper, which gives added value to the work. Is it due to material shortages or the need to prolong the artisan aspect that distinguishes engraving, without undermining its artistic value?

Manufactured paper has an antecedent in the Craft Paper Workshop, which was designed by Paneca. Eusebio Leal later assumed the property as one of the many institutions of the Office of the City Historian. I was in Mercaderes, in front of the La Torre de Marfil restaurant. I don’t know if it still works in that place.

Several Cuban engravers have made their own paper. However, I had not been interested in that practice to do my work. At the end of my graphic period in 2019, I visited Oaxaca. There I saw a marvelous craft paper workshop founded by Francisco Toledo, that great figure of Mexican art.

When I returned to Havana, the painting fever seized me. I had been painting on canvas and, really, I never stopped doing it; but I wanted to experience something else.

At that time I received a visit from Lesbia Vent Dumois. I showed him the work on paper; she loved it and motivated me to follow that path. She suggested that she request space to exhibit at the Villa Manuela Gallery; but I kept painting on canvas. When Virginia Alberdi saw everything, she told me: “We are going to reach an agreement with Lesbia. We expose paint and finish with paper, to show the new path”. So we did. Later I stopped painting on canvas and began to make those papers that I have been publishing on Facebook. I do not stop. Every day I like them more, and the reception has been very good.

Now, in February, I will exhibit them in Uneac’s Sala Villena, to celebrate my 70th birthday and half a century of work. But, I repeat, they are not engravings, but acrylic on manufactured paper. Engraving was left behind, like a long period that gave me great joy.

If you were given to collect Cuban art, which artists would you choose?

Those of the first vanguard and the later: Mariano, Portocarrero, Lam, Amelia, Oraá, Antonia Eiriz…; I would add Tomás Sánchez, Nelson Domínguez, Fabelo, Pedro Pablo Oliva, Villa Soberón, Sergio Martínez, and the entire Cuban poster linked to the cinema of the 60s, 70s and part of the 80s.

How do you reach 70 years?

Sick, but full of desire to continue working, with achievements in the last two years, such as the inclusion in the Cuban art collection of the National Council of Plastic Arts, the incorporation into the Uneac collection and, the greatest joy of all , the acquisition of a pictorial piece of mine by the National Museum of Fine Arts. Maybe for others it doesn’t mean much. For me they are the greatest prizes that life has given me on an artistic level: the recognition of specialists.

I have to add that if I have achieved anything in life, it has been because of the understanding and love of my family: Vivian, my daughters Adnaloy and Ana María, and my grandson Pepe. Without them it would have been impossible.

Before, I worked around ten hours a day. I can’t do it anymore; Now I stick between four and six hours. The forces do not give me for more. But if I manage to get out of this, you can be sure that I’ll go back to painting like before.

you will go out

Thank you. For that I fight.