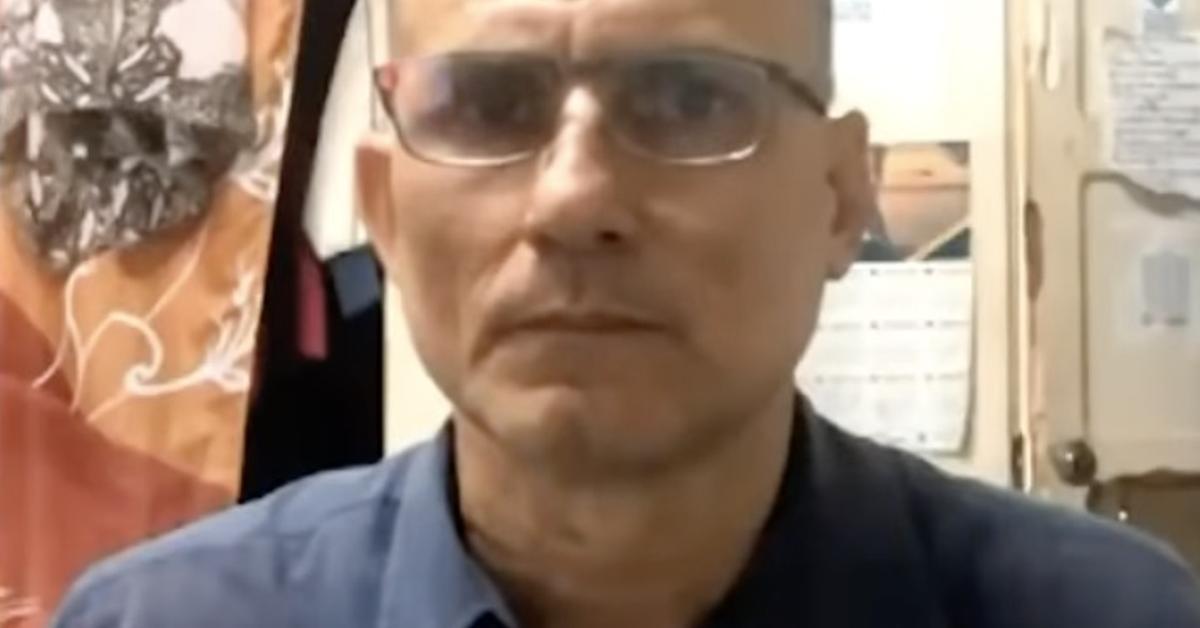

Havana/The phone has been busy all afternoon. Since this Thursday the opponent Jose Daniel Ferrer He was released from the Mar Verde prison in Santiago de Cuba and has not stopped giving interviews. Finally, I hear his voice on the other side. He has the same firm, kind tone I remembered. The dungeons and abuse do not seem to have taken away either his energy or his sanity. We started talking as if yesterday we had paused this conversation that I share with you.

“What I feel right now is a little sad for not having been able to answer everyone who wanted to talk to me,” he admits, overwhelmed by the many calls. Leaving prison is an overwhelming experience, the sounds stop being just the squeaks of the bars and begin to also be familiar voices; The light changes and they are no longer shadows, but blinding flashes, and the body itself still does not know how to move, even though the space is as close as the house itself. The veteran opponent has experienced these sensations many times, but they do not stop shaking him.

Ferrer has been welcomed not only by his family and neighbors but also by the blackout. “Now I am with a rechargeable lamp because shortly after I arrived the power went out.” The Cuba that he has found on this side of the walls of the penitentiary center is a much more economically deteriorated country and also with fewer hours of electricity supply. “Even so, despite everything, I have already been able to give a hug to some brothers in the struggle, physical and virtual, through the Internet,” warns the tireless leader of Unpacu.

Although the days in captivity were full of bad moments, Ferrer also tells how humor helped him unsettle the jailers.

Although the days in captivity were full of bad moments, Ferrer also tells how humor helped him unsettle the jailers. “I once heard at the Round Table that the Minister of Agriculture wanted to improve egg production with more political and ideological work on the workers in the sector.” When the guards approached him that day, the dissident’s incisive irony could not be missed: “You have already heard that chickens have to understand that even if there is no feed, they must lay eggs.” The long face of the military was the only response.

Every so often during this conversation you can hear the voice of a little child on the other end of the phone. Ferrer’s son, Daniel José, demands the attention of a father with whom he has spent very little time due to the rigors of prison and the isolation to which the political prisoner was subjected. “Now I’m coming,” the father warns him and continues interspersing phrases about his time behind bars while he attends to the little boy’s demands. You can imagine him with his cell phone in one hand and a toy car in the other, trying to distract the little one.

His daughter Fátima, 20 years old, has also traveled from the community of Palmarito to welcome her father. He has been able to speak only partially with the part of the family exiled in the United States. He already spoke with his sister Ana Belkis Ferrer, who kept an updated report on what Ferrer experienced in prisondenied family visits and deteriorating health. “I still need to talk to my brother, my mother and my other children, but I will do it, I will do it,” he says.

“When I got home I got such a rush of adrenaline that I thought I was 18 years old.”

“When I got home I got such a rush of adrenaline that I thought I was 18 years old,” he admits, although he also remembers that he should avoid those bursts of enthusiasm because he has problems with blood pressure and needs to take Enalapril to control the spikes. depression. “The adrenaline has returned to its place and I am 54 years old again,” he warns. His body, battered by confinement, poor diet and lack of sunlight, now sets the tone, sets the pace.

In the book that Commander Huber Matos wrote after leaving prison, where he spent 20 years for denouncing the communist drift of Fidel Castro’s regime, he recounted a scene in which he got up to go to the bathroom and found himself, for the first time in two decades, with a mirror that showed him his entire body. On the pages of How the night camethe former political prisoner described the surprise of seeing a graying and aging man looking him in the eyes. Ferrer is also now discovering his image, specifying the contours that the dungeon blurred, visually recomposing his anatomy.

Despite the mistreatment, on his last day in prison he had words full of future projections for his jailers. “The democratization of Cuba is also convenient for you,” he told them before leaving and added a knowing wink full of irony that the guards did not expect: “Vote for me for the presidency because I know that your salary is not enough.” and they are going through a lot of difficulties.

“I know that you have to work on the left to survive,” the opponent continued explaining to them.

“I know that you have to work on the left to survive,” the opponent continued explaining to them, while making with his hand the gesture that is used in Cuban streets for the act of stealing and diverting State resources. In a prison, from the boss, through the jailers and even the workers further down the scale, they steal food and other resources intended for the inmates to support their daily lives. That truth, as big and solid as the walls of a prison, cannot be denied, so silence spread after Ferrer’s words.

“Just go home,” the officers almost begged him in response to the dissident’s tirade. An uncomfortable prisoner must be worse than a stone in the shoe for soldiers who are not used to being contradicted or warned that the regime they support with their weapons and uniforms can fall like a fragile house of cards in any time. The henchmen must believe that their impunity is eternal because imagining a future in which they are held accountable puts them before another mirror, that of responsibility.

“On the days when they were going to beat me, they took the highest-ranking officer of Mar Verde out of the environment, so that later I couldn’t say that he was aware of this mistreatment,” he recalls. “Yesterday he told me to finish leaving with my wife and my son, not to continue protesting.” But Ferrer took it calmly and wanted to make it clear that he did not accept any blackmail linked to the release of political prisoners after the talks between the Cuban regime and the Vatican, in parallel with the announcement made by the Joe Biden Administration in the United States. to exclude Cuba from the list of countries sponsoring terrorism.

“I want my things, my books, my writings, my verses,” the prisoner claimed. “I was writing quatrains, a few days ago I finished the first part of one that was about braggarts, those people who claim to have courage that they don’t have, I said: ‘Juan, in a bar in Havana/ under the influence of rum/ without gun, kill a lion / in the African savannah.'” Just the night before his release, Ferrer had finished the last stanza: “Juan, now without the drunkenness/just seeing a mouse/his heart shakes/and all of Havana runs.”

“Yesterday he told me to finish leaving with my wife and my son, not to continue protesting”

“When I got up this Thursday, one of my sources inside the prison warned me that Mar Verde was full of bosses from all over Santiago de Cuba, ‘there are also those from State Security and it is being said that you are going free, They are in those preparations.'” Shortly afterward they informed him that it was a “conditional release”, to which Ferrer refused: “I do not accept conditions, they can give me all the warnings they want but I do not comply with them.”

The prisoner sent them a defiant message: “You are going to be prosecuted in the future and you will be condemned for all this, but I can assure you that you will not have to face the hunger, the bedbugs or the tuberculosis that we have to suffer.” political prisoners in Cuba”. Finally “they kicked me out of there, they didn’t let me pick up my toothbrush, my family photos, my books, nothing.”

Outside, his wife Nelva Ortega Tamayo and his little son were waiting for him. For her he only has words of gratitude. “He went through very difficult times while I was in prison: he lost his mother and recently his grandmother also died,” adds Ferrer. “It is one of the most difficult things about being imprisoned, that helplessness of not being able to be next to your loved ones in the most complicated moments they live to encourage and support them.”

Now, Ferrer plans a visit to Havana, where he has a daughter he has not seen since before the arrival of the pandemic. The last part of the conversation is to remember our time together as friends. A pizza eaten in company, a hurried hug, some laughter among personal testimonies. “See you, my brother,” he closes the talk, as if we had left it on pause a few hours before and this Thursday we were only resuming it to catch up with the latest details: the news to which anecdotes, future projects are always added and even verses.