HAVANA, Cuba.- Back in 2017, Contreras (the pitcher of Major Leagues) met in Pinar del Río with Contreras (the one who writes this text). They merged into a hug where they exchanged three or four compliments. Then, laughing, the pitcher alluded to the famous inheritance that, supposedly, fell to everyone who bore the surname.

—And then, relative, when are they going to distribute the money from the Contreras inheritance? -asked.

—They already did it, buddy. You took it all by signing for 32 million with the Yankees.

From his almost two meters tall, the star burst into thunderous laughter. Then we had a few drinks and talked at length about baseball. Pedro Luis Lazo He was with us and also the now deceased Jesús Guerra, his mentor, who discovered the dark-skinned man’s talent and saved him from growing old at the foot of the furrow in Las Martinas.

The minutes that fit into two hours were enough for me to be eternally impressed with the simplicity of that millionaire peasant. He dressed without stridency. He spoke as if he were whispering. I was gesticulating, I said one day, with the slowness of a bandoneon.

He told me that when he arrived at the Yankees clubhouse he had a bag with his glove and some spikes stained with red dirt. That they gave him a box office—wow!—between Mariano Rivera and Roger Clemens. That Derek Jeter was an incredible teammate. “The best I’ve ever had after my dog,” he emphasized, pointing his index finger at Lazo.

Lazo and Contreras are brothers. They grew up together on national grounds, they shone side by side, and they call each other “my dog” with the naturalness that others call each other “tank”, “asere” or “bro”. At the time they became the Twin Towers of Vegueros and Team Cuba, they combined to give away scones of ‘ponchaos’ and oxygenated the legend of a ball that, at that time, was venerable.

The dynasty of the yunt lasted a decade, and it would have extended much longer had it not been for Contreras changing course. Lazo remained on the Island and ended up becoming the top winner of domestic championship games; more daring, he deserted in Mexico, jumped to the United States, collected the money that corresponded to the surname and crowned with a World Series ring. All this in a period of three years.

It’s a shame he landed in the MLB when he was over thirty years old. However, he had time to shine: overall, he threw ninety-odd sustained miles, he had a good slider, a brutal fork, and he could throw each of those pitches in all counts. Radically put, a crack.

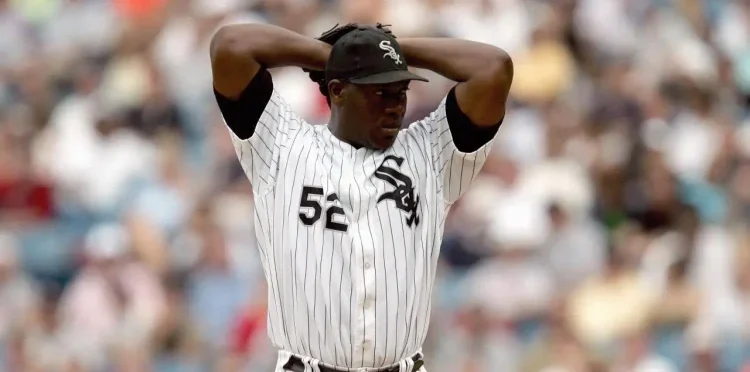

Thus he became immortal. Almost always with the ’52’ in the middle of his back, wherever he performed he carried those arts with him to inspire respect from the most spontaneous sobriety. He didn’t scream, he didn’t assume forgiving poses or try serial killer looks. He lacked the inner fire of his “dog,” but he imposed discipline with the whip that God placed in his throwing arm.

When you say José Ariel Contreras, there are those who think of a sweaty guy who dominated his opponents one after another. There are those who point out that he could not succeed in the Yankees, and those who see the positive side by adding that he won three games in the 2005 postseason, including the victory over the legendary Clemens.

In my case, the first thing I manage to do is remember that once, at number 268 Martí Street, I sat down to enjoy a talk with the simplest guy in this world. That day, as I say all the time, I collected (and with a tip) the Contreras inheritance.