H

a few years ago, in a conference at CIDE, the sociologist Saskia Sassen pronounced a lapidary phrase: talking about inequality is an invitation not to think

. His proposal consisted of dismantling the concept, too hackneyed, to allow a new look and reflection on the subject.

Something similar happens when we talk about structural causes

of migration, which in the end is saying everything and nothing. There are so many factors that can influence the decision to emigrate that we can list twenty: poverty, underdevelopment, inequality, unemployment, demographic pressure, economic, political, social, cultural and domestic violence, gang activity, drug trafficking, political, religious, generic persecution. , ethnic, linguistic and cultural, as well as the systematic violation of human rights, state capture, corruption at various levels, natural disasters, institutional impunity, etc.

In addition, it influences the demand for labor, recruitment, wage disparity, policies favorable to immigration and refuge, legal and informal family reunification and the so-called cumulative causality that allows the migration process to increase and perpetuate itself on a larger scale. family, generational and community with the support of social, family and peasant networks.

The structural causes of migration, which obviously exist, must be tried to rank them and specify their degree of influence at a given time. For example, in Central America, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Nicaragua are captured states

but with a very different cut, in Guatemala it is called corrupt pact

the one who controls the country; in Honduras it was the oligarchy linked to drug trafficking and there has just been a change of powers; in El Salvador he is the leader of the New Ideas party and its parliamentary majority; in Nicaragua it is the dictatorship exercised by the presidential couple. In all four cases, the political context exerts pressure to emigrate.

In Mexico, demographic pressure was a fundamental factor for emigration in the second half of the 20th century, with an average of seven children per woman in the 1960s and 1970s, which continued until the beginning of the 21st century; Likewise, the recruitment during the Bracero program and later the permissiveness for Mexican workers to work in agriculture in an undocumented manner have generated a specific labor niche.

Currently, the birth factor no longer counts, given the demographic transition process (2.1 children per woman) that led to an initial migration transition process, which manifested itself in a notable way with the decrease in undocumented emigration from 2007 to 2020. Similarly, there are sectors of the economy and certain regions where economic pressure and wage disparity do not clearly manifest themselves as push and pull factors.

On the contrary, the historical factor of Mexican migration operates in an important way in legal migration. On average, some 170,000 resident visas are granted ( green card) annually to Mexicans. The vast majority of these visas are granted for family reunification processes. On the other hand, some 110,000 Mexicans are naturalized each year. Both the residence visa and nationality grant rights to initiate new reunification procedures.

Recruitment continues to be another important factor, some 240,000 visas are granted annually for workers in agriculture (H2A) and about 60,000 for services (H2B). In addition, there are many other types of visas that Mexicans can access, for business ties, studies, the free trade agreement and others.

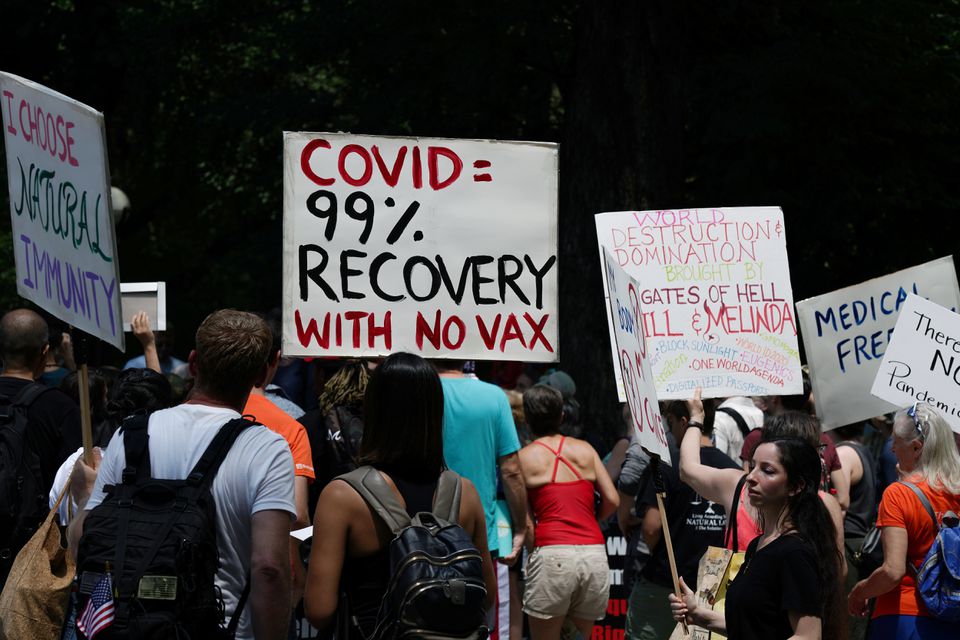

As for undocumented migration, many factors operate, according to each particular case, but currently the covid-19 pandemic is a factor that we did not have before and that has exacerbated other factors, to which are added inflation, limited economic growth and loss of purchasing power.

In the case of violence in Mexico, several studies report an important impact on internal migration, not international, it is properly speaking displaced migrants. On the contrary, in wealthy sectors, systemic violence, kidnapping and extortion have generated the emigration of families to cities in the neighboring country.

Today we can rethink the structural causes

of migration from three analytical categories adjusted to the present: neoliberal poverty, systemic violence and institutional impunity, a topic that will be developed in a second installment.