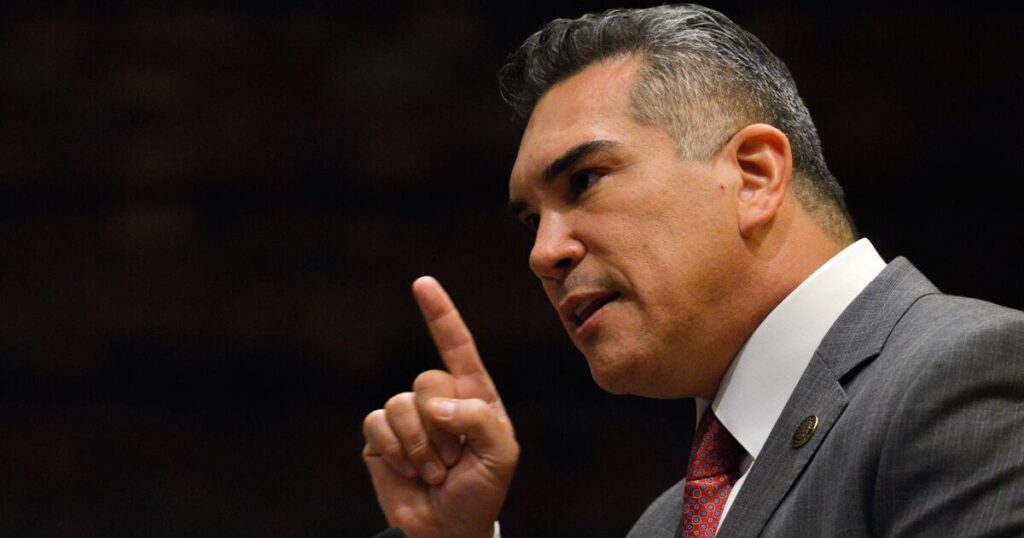

At the gates of a meeting this Wednesday of the Permanent Council of the Organization of American States (OAS), in which diplomatic sources assure that Secretary General Luis Almagro will finally present his report on the failed efforts on the crisis in Nicaragua, former Mexican Foreign Minister Jorge Castañeda said on Sunday in the program This week that there are not many expectations about the possibility of the Daniel Ortega regime being suspended.

Although the former minister believes that the votes do exist for the approval of a critical report, he does not think the same will happen if the decision is to suspend the OAS regime, invoking Article 21 of the Democratic Charter.

On November 12, the OAS decided with 25 votes of 34 members on a resolution that declared illegitimate voting in Nicaragua, with whom Ortega achieved a fourth continuous presidential term—since 2007—demanded the release of political prisoners, the restitution of their democratic rights, and an electoral reform to call new elections.

Ortega has shown a rejection of any diplomatic negotiation, based on the argument that he is the object of interference in internal politics. Almagro’s report should have been presented on December 17. However, the OAS Secretary General extended it until mid-January, after he reported that there was no “one definitive answer in particular” from Ortega.

Castañeda lamented that Argentina and Mexico have aligned themselves with the position of recognizing Ortega as a “legitimate president”, after the spurious votes last November, because if they “voted in favor, for example, of invoking the Inter-American Democratic Charter and suspending Nicaragua, that would have a very important impact”, he said in the interview with This week.

How do you read the absence of delegations from the majority of democratic governments in Latin America in Ortega’s self-proclamation on January 10?

It is a reflection of the attitude that many governments had of ignoring the results, not considering that they were fair, competitive, free, open, and transparent elections, and therefore not de facto recognizing Ortega as president of Nicaragua.

What is remarkable, more than not sending delegations—something other times seen in dictatorships—is that countries that maintain diplomatic relations with Managua, that have ambassadors and their business managers in Managua, did not attend the ceremony. That is a very powerful, important signal that countries do maintain their position of condemnation and ignorance of these fraudulent, spurious, farce elections.

Is the position of Mexico and Argentina to maintain this complacency with the Ortega dictatorship invariable in the medium term?

I get the impression yes. After many comings and goings, of somewhat erratic changes by the Argentine Foreign Ministry, with different votes in Geneva or in the OAS, finally I believe that they have aligned themselves with the position of Mexico, Cuba, Venezuela, Bolivia, of considering that Ortega is simply the legitimate president of Nicaraguans and to establish a completely normal relationship with him.

In the same way, there were certain attempts by the Mexican Foreign Ministry to be a little critical, at some point they called the ambassador for consultations, but at the end of the day both in the OAS, Geneva, and now in Managua, they have remained in an identical position —I insist— to that of Cuba, Venezuela, Bolivia, of course it was not a high-ranking Mexican official, neither the foreign minister nor the president as Maduro and Díaz-Canel did.

This is something that is going to last and it is unfortunate because in the OAS, in particular, if Mexico and Argentina voted in favor, for example, of invoking the Inter-American Democratic Charter and suspending Nicaragua, that would have a very important impact. Regardless of whether Ortega has said that Nicaragua is withdrawing from the OAS, it is a process that lasts two years, while invoking the Charter could be done immediately.

In Latin America there has recently been a resurgence of some leftist governments, Boric in Chile, Xiomara Castro in Honduras, while Petro in Colombia, Lula in Brazil are also favorites to win elections in their countries, what impact can this trend in the democratic agenda of the continent?

Much will depend on the position adopted by these new presidents. In the case of Boric and Pedro Castillo in Peru, and Xiomara Castro in Honduras, Lula and Petro in Brazil and Colombia in the face of the situation in Nicaragua and Venezuela. Boric made very strong, critical, democratic statements during the campaign. Therefore, I do not believe that it will align itself with the Bolivarian axis of defense of the three dictatorships. Pedro Castillo in a vote at the OAS commanded a critical stance and did not send a high-level delegation, much less to Managua.

Lula unfortunately seems to me that, although he will undoubtedly follow a much more centrist course in Brazilian internal politics, than Vilma Rousseff did before and what the PT would like now, he will follow the same (path) in terms of politics exterior that he followed during his two periods at the beginning of the century. That is to say, a path of certain unconditionality against Cuba, Chávez at that time and now against Ortega. I’m sorry.

In Honduras, not much changes. For his own reasons, Juan Orlando Hernández has become a very close ally of Ortega. He was present at the ceremony in Managua. In that sense, the change will not be noticed, although the reasons may be very different in the case of Hernández and Castro.

Next Wednesday the OAS Permanent Council meets, and the Secretary General is expected to present his report on the negotiations with Ortega. What options would Almagro have?

Very few. In the previous vote, 25 countries out of 34 voted in favor of a damning draft resolution. Those votes are there and they still are, because in any case the Chilean government that will vote will be the government of Piñera, the Colombian that of Duque, the Brazilian that of Bolsonaro. Almagro has the votes to approve a critical report, but I don’t think he has enough votes—two thirds that are needed, that would be 24—to invoke (article 21 of) the Democratic Charter. I don’t expect much.

Does the US, the international community, have a medium-term strategy in the face of the crisis of the Ortega regime in Nicaragua, which has no immediate solution?

Nobody has it because it is not so easy to have it. Beyond the enormous sympathy they may have for the political prisoners, who find themselves in an abominable situation; Beyond the desire that we can all have for a return to democratic normality in Nicaragua, the dilemmas are real for the United States, the European Union, for any country, what to do? Sanctions?

Those that are personal have the advantage that they only affect people, but they also have the disadvantage that they don’t really bite. Removing someone’s visa or freezing someone’s account assuming they had it in the United States, is not something that represents the end of the world for Daniel Ortega or Rosario Murillo.

On the other hand, more powerful sanctions such as the exclusion of Nicaragua from CAFTA (Central American Free Trade Agreement with the US), or the expulsion of Nicaragua from the OAS, IDB, WB, IMF can be ineffective and at the same time hurt much to the people of Nicaragua, but not the personal economy of Ortega or Murillo. My inclination is in favor of sanctions, I don’t like the idea of doing nothing. But I cannot ignore this negative impact.

Can a conditionality be established between sanctions and the restoration of democratic freedoms and the release of political prisoners?

Of course yes, because there are instruments. The option of Nicaragua’s suspension from CAFTA does not necessarily have to be used. What is not clear is that this will help restore freedoms, release prisoners, suspend the emergency regime, it is very difficult to know what to do.

Since the approval of NAFTA (the free trade agreement between Mexico, the United States and Canada in 1994), I have been in favor of linking free trade agreements to respect for human rights, defense of representative democracy, individual guarantees, but America doesn’t like it. To the European Union, yes.

What repercussions would the prolongation of Ortega’s dictatorship in Nicaragua have for Latin America?

These are unfortunate consequences, very critical because it would be for the rest of Latin America to accept a dictatorial normality in one of the countries, without having the pretext that this existed before, let’s say the case of Cuba. It would be simply by resignation. An important juncture will be the Summit of the Americas to be held at the invitation of President Biden in July.

There will be a very complicated moment. Is Biden going to invite Díaz-Canel, Maduro, Ortega and Bukele, by the way, who is in a very similar situation, not as serious, but similar to Ortega’s? Are you going to invite them and what are the Latin Americans going to do? Will they greet them like ordinary colleagues or will they treat them like dictators?

If the final solution to the crisis lies in Managua, and not in Washington, can the international community get some other form of support for the political opposition in Nicaragua?

I do not know the details of what is already being done, but I suppose that much more can always be done, both the United States and Canada and the European Union, and now England, have many mechanisms to support civil society, to respect human rights human beings, to a full representative democracy.

In Nicaragua there is enormous frustration over López Obrador’s position in this crisis. Does he have support in Mexican society?

What there is in Mexico against Nicaragua is indifference. There is not the kind of commitment that there was against the Somoza dictatorship. López Obrador is aware that he can maintain this position without any external political cost.