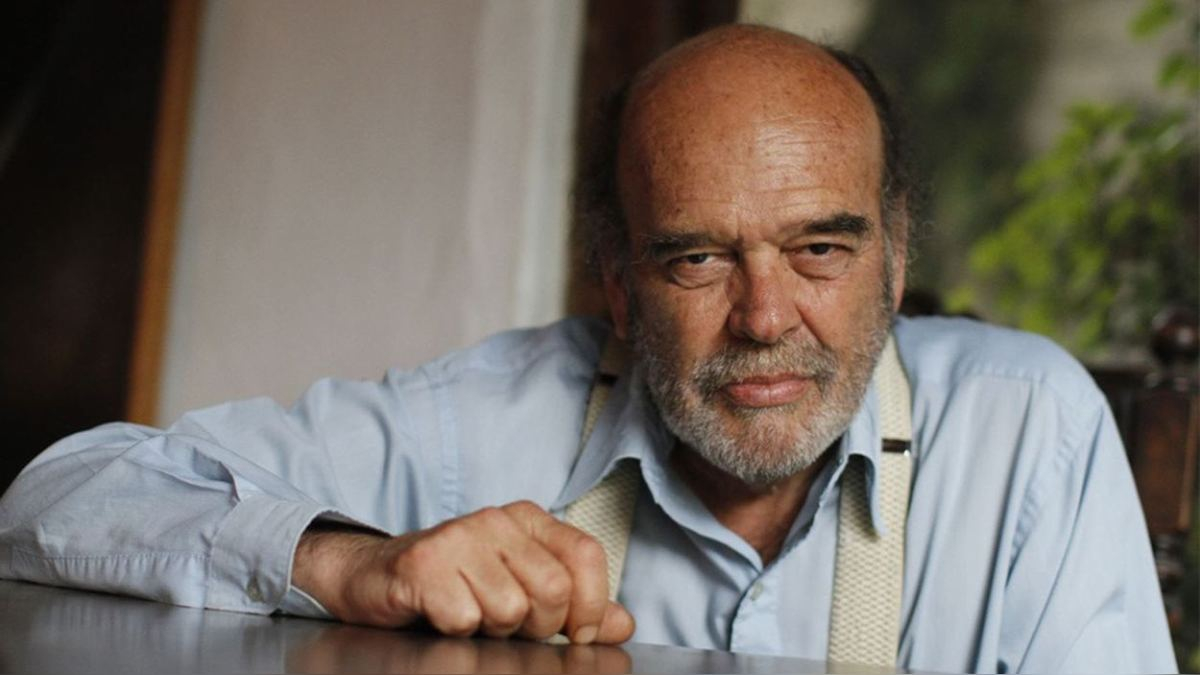

The journalist and writer Luis Jochamowitzauthor of Citizen Fujimori and Vladimiro: life and times of a corruptorabout the former dictator and his advisor, among other books, reflects on the Alberto Fujimori’s departure, the farewell from his family, followers and the current Government; the memory of his regime and political life; and what remains of Fujimorism without its founder, and of the Fujimoris.

—You shared a reflection on Alberto Fujimori and lying. How marked was this characteristic?

—I would say it was central: lies, deception or lack of informationin various ways.

—And much more serious events. However, he had a multitudinous farewell. How do you explain it?

—When Juan Velasco died, there was also a large crowd, and a dowsing journalist, Manuel D’Ornellas, said that the Peruvian people were necrophiles: they are moved by death. Maybe that is the case. And there are other reasons; we must not deny Fujimori’s importance. I was critical, but I have no difficulty in remembering some of the events of his government.

—Which ones mainly?

—Many. The main one, and perhaps the one that moves people the most, is that he personally took care of almost everything. If a blanket had to be distributed in Huánuco, he personally did it. He flew in by helicopter that morning and at noon he was there with his blanket and distributed it. These are unforgettable events for many people. Those who received that blanket will never forget it.

—Is that something he did or was it concocted by a consultancy?

—He read that. He read an author, William Deming, who talked about micromanagement, which is to say: don’t delegate, do it yourself, if you want to be remembered.

—It’s Fujimori’s harvest…

—He had very distinct characteristics. I remember a video of him with scissors and a manila envelope, cutting it up to reuse it or give it two lives, about 5 minutes. He loved to get the most out of the material.

—You have recalled something that 24 years later many have forgotten, that Fujimori had a kindred spirit: Vladimiro Montesinos. There was talk of Fujimontesinism, but now it is rarely used…

—Actually, they were Siamese twins. It’s a very long and complicated word: Fujimontesinism.

—How much was Fujimori and how much was Montesinos? Were they very similar or very different? How did this symbiosis arise?

—We would have to observe it, but neither of them has said anything. They keep quiet about their relationship because it is very compromising. They prefer not to say anything because it would be incriminating themselves. What we know is that they lived together for practically 10 years.

—When it falls, after the vladivideo For 24 years, Montesinos has been blamed for all ills.

—As a scapegoat. But there were both of them. Fujimori was the boss, I have no doubt about it. And Fujimori let him do it. He would pretend not to know, but he couldn’t ignore certain things, like the fact that there was a huge amount of money flowing to the SIN (National Intelligence Service).

—And Montesinos at first starts to push Fujimori away and even involves Keiko for the payment of her studies, but then he remains silent and time has made much of it forgotten…

—Too many years and events have passed. Of course, time always produces that

effect, that people forget.

—Now, is Fujimorism strengthened or weakened by the death of Alberto Fujimori?

——He will be strengthened in the short term: they speak wonders, they call him the best president… Afterwards he will weaken unless he has a dynasty, leaves a legacy, leaves some good administrators. Keiko has not proven to be one so far.

—He has already lost three times when he was close to winning, with the Presidency on the brink of failure…

—He is in the chapel, but in politics nothing is definitive. What seemed impossible to us can happen. And another heir appears, who is Kenji.

—At the funeral, many people shouted “Kenji, President!” Before, at the mass, Keiko was also called President, but less often…

—Keiko is the stain: she behaved badly with her brother, with everyone, even with her father. Kenji, on the other hand, was quiet, he was willing to make any concession, to come to an understanding with Pedro Pablo Kuczynski and to get rid of his father. So, that puts him in a better position.

—If Fujimorism strengthens in the short term, would Keiko rise a little in the polls?

—In the very short term. It will surely rise, but let’s wait two, three months or until the elections to see how many people remember it as they do now.

—Fujimori was pardoned, but then he said he was going to be the presidential candidate, welcomed by Keiko despite his age since they had said he was in very poor health.

—They are indestructible. I heard Keiko’s speech in Huachipa. Some things were incredible. It was a mix of politics and death. Keiko said that they went there a short time ago and he said: ‘I want to be buried here near Susana, but not together’, as if to say ‘we have come close, but not that close either’.

—The political use made of the honors to Fujimori in the National Grand Theater and in the cemetery has been questioned, as it seemed like a campaign, to the tune of ‘El ritmo del Chino’, calling for unity and with promises to build a better future…

—It was a mixture of death and politics. Quite disconcerting. I thought: what bad taste! Then I thought: there is no solution, that’s how we Peruvians are or that’s how they are.

—Do you consider this a valid use or is it already an excess of calculation on the part of Fujimorism?

—I think it’s in bad taste, horrible. One would expect the death to be closed and a personal or family mourning and nothing more. You’re not going to be making money off of it in a few years.

—Did Alberto Fujimori’s announced presidential candidacy also have something of this calculation, this exploitation?

—Whoever announced it knew that Fujimori had advanced cancer and was not going to make it to the elections in perfect health. I think his daughter knew that, but despite that, she announced it as if to say: let’s see, we’ll take a chance and see if we get it.

—The doctor said that Fujimori wanted to try the treatment. Keiko said that she did it despite the risk because she wanted to serve Peru.

—In their ambition, they are indestructible. Now they have left behind a dynasty that is another form of eternity, right? You don’t rule yourself, but your children, that is, your genes, rule. That is very oriental. In Peru, as far as I remember, there has been no dynasty.

—When the rot exploded in 2000 and Fujimorism was left with three congressmen, it seemed like the end, but it has grown, it has a school and there are young Fujimorists who have not lived in the past, but who have the discourse that he was the president who saved the country.

—It’s amazing, I find these things amazing. It must be because I lived in another era and it seems almost inconceivable to me… People who didn’t know anything about the nineties can believe everything they are told.

—Is impunity a legacy of Fujimori? He never admitted to crimes that some supporters justify by the war against subversion, and he obtained an irregular pardon, even though his sentence was seen as an example from Peru to the world. What remains?

—He never wanted to admit to his crimes. He is an enormously controversial figure. I, who have been an opponent all my life, cannot deny that Fujimori has been one of the most decisive presidents we have had in the 20th century. Perhaps he is comparable only to Leguía in the 1920s or to Velasco in the 1970s. I am not saying that he was better or worse, I am just mentioning precedents. The other presidents pass like lukewarm water compared to those who have transformed the country for better or worse.

—What did you think of the recognition that the Dina Boluarte Government gave you?

—It was so symbolic. That reveals which side you’re on, more than a vote in Congress. Giving him three days of funeral honors, flag at half-mast… At least they’re leaving hypocrisy behind and standing in line before the illustrious man they’re saying goodbye to. He’s the one who gave them everything. He’s the foundation of the current regime. We’re heirs of those years. Without him we would be incomprehensible. Peru has changed.

—What will be the most difficult thing to overcome about Fujimori’s legacy?

—Recreate good faith: of the judge, of the Peruvian republic towards its own citizens… What we owe to the Peruvian citizens. After Fujimori, it is very difficult to believe in the truth. A character who has made bending the rule… In reality, part of the responsibility lies with the Peruvians. Fujimori was like a mirror in which we saw ourselves and saw what we wanted: if we wanted to see an honest Chinese, there he was; if we wanted to see a cheater, there he was. He was like an empty mirror in which we projected ourselves endlessly. In fact, for 30 years, we have projected ourselves in him, in that mirror. Fujimori knew that. And he smiled with great skill. Before he was very dry, before I mean at the time of the University of La Molina, he was famous for being dry, never smiling, but when he began to do university politics, at first he began to smile and he realized that this was a mechanism to convince everyone, the multitudes. And in 1990, in the elections against Vargas Llosa, he won because Vargas Llosa made big mistakes, but Fujimori was remembered with a smile, saying: “I have nothing to do with it, I am new.” And it was true, he was new. Then, the rest came.

“There can be no forgetting without justice, that is the problem”

—How do you see the upcoming elections in relation to Fujimorism? Does Keiko have a chance or should it be Kenji?

—About Keiko, if I were from the interior of Peru where they said it was fraud and my vote was worthless, I would be furious with Fujimorism.

—And Kenji has a chance?

—It’s quite basic, Kenji. Maybe that’s a plus, unfortunately.

—What should the next generations do regarding the Fujimori issue?

—The ideal would be to leave him alone. When I wrote my book, I thought: “I publish it and that’s it.” No, he has pursued us. These days there is talk about his death, but if he runs for office again, we will return. Psychiatrists talk about echolalia: when they repeat a word over and over again. Peruvian politics is echolalic to a certain extent. We don’t turn the page, we keep repeating the same phenomena, the same processes…

—And so we don’t move forward

—Because we don’t solve the problem, we don’t move forward. If we were to stamp it as cancelled, it would simply be behind us. We don’t cancel it because we don’t solve it.

—The solution for them, according to Keiko’s speech and which embodies Fujimorism well, is ‘stop with irrational hatred’. It is the seal they want.

—It’s not bad to stop hating. Cancel it, forget it, end it, but solve it.

—Is justice necessary or can it be ignored?

—There can be no forgetting without justice, that is the problem. That is why we are not closing the page, because there is no justice. If there were justice, people would, on their own initiative, forget about Fujimori and go and see what our future holds. It would be good for us to discuss that, what we have to do in the future.

—Was it feasible for Fujimori to accept responsibility, repent and ask for forgiveness?

—The facts have shown that this is not the case.

—Out of cowardice or to maintain a myth?

—You would have to get into his mind. Maybe he told his children: I regret this and that. For example: I regret having associated myself with Montesinos, I should have looked for the best people. He didn’t say that. He looked for the worst. Why? Because it suited him. The same with human rights. Besides, there were financial reparations there. He didn’t want to pay a cent. And he didn’t pay.