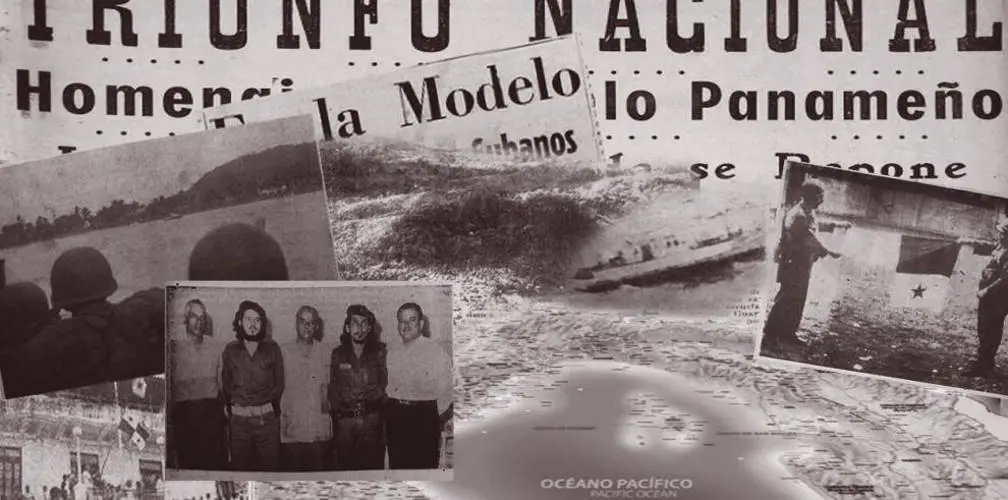

MIAMI, United States. — On April 15, 1959, the government of Panama denounced before the International Community an invasion plan by the recently installed government of Fidel Castro. Days before, a group of young people who belonged to the Revolutionary Action Movement (MAR) had assaulted an armory to immediately go into the mountains, calling for insurrection.

During the following six days, the National Guard deployed an operation that put an end to the uprising, with the death and capture of several guerrillas. Thus it was learned that two hundred men were being trained in the Cuban province of Pinar del Río, under the orders of the commander of the Revolution, Dermidio Escalona. The military action was being promoted by Roberto Arias, nephew of the former president of Panama, Arnulfo Arias Madrid.

On April 19, a ship with 85 crew members and heavy weapons left the Cuban coasts. Two Panamanians, including Enrique Morales —invasion leader—, and an American were part of the expedition. The rest were Cubans.

The National Guard of Panama tried to prevent the landing, but the invaders, imitating the modus operandi of Fidel Castro, they divided into several groups to establish the bases of the uprising in different locations. However, in the following days, three guerrillas were captured and presented to the International Community as proof of the military operation organized from Cuba.

At the end of April, a commission from the Organization of American States (OAS) appeared in Panama. By then, the National Guard had surrounded the insurgents, who proposed to surrender in exchange for being returned to Cuba, to which the Panamanian authorities refused. On May 1, by express order of Fidel Castro, the rebels surrendered.

The attempt caused an international scandal that damaged the image of the Cuban Revolution and its leader. Justifications immediately rained down from Ernesto Guevara, who claimed that the Revolution “exported revolutionary ideas, but not the Revolution itself.”

Fidel Castro, who was in the United States, washed his hands of it and described the invasion as shameful, untimely and unjustified. The Cuban government had to offer guarantees to Panama that a similar event would not be repeated.

The failed invasion was the first step in the diplomatic cooling between Havana and Washington. From then on, the media and power groups in the United States and Latin America changed their perception of the intentions of Fidel Castro, whose interest was always to export the Cuban Revolution to other countries on the continent.

The actions in Panama were the starting point for the spread of guerrilla and terrorist groups in several Latin American countries, with the purpose of exporting the Cuban revolution and destabilizing the region.