In an official response from the Ministry of the Interior, the practice of collecting personal data from open sources for the prevention and investigation of crimes was confirmed, which falls within the concept of “cyber-patrolling” for police purposes. This statement was one of the responses given following a ruling by the 4th Court of Civil Appeals following a lawsuit filed by Datysoc, a project belonging to the civil association Data Uruguay, dedicated to the analysis of the impact of information technologies on human rights.

The Ministry of the Interior also responded affirmatively to the query about whether studies, regulations, proposed regulations or documents with data obtained from open sources had been carried out or approved. The document, signed on June 17 by José Manuel Azambuya, director of the National Police, was obtained by the weekly Search.

Datysoc’s initiative to go to the Judiciary was motivated by the lack of response to a request for access to public information submitted in 2022, within the framework of a regional investigation published the following year without official responses.

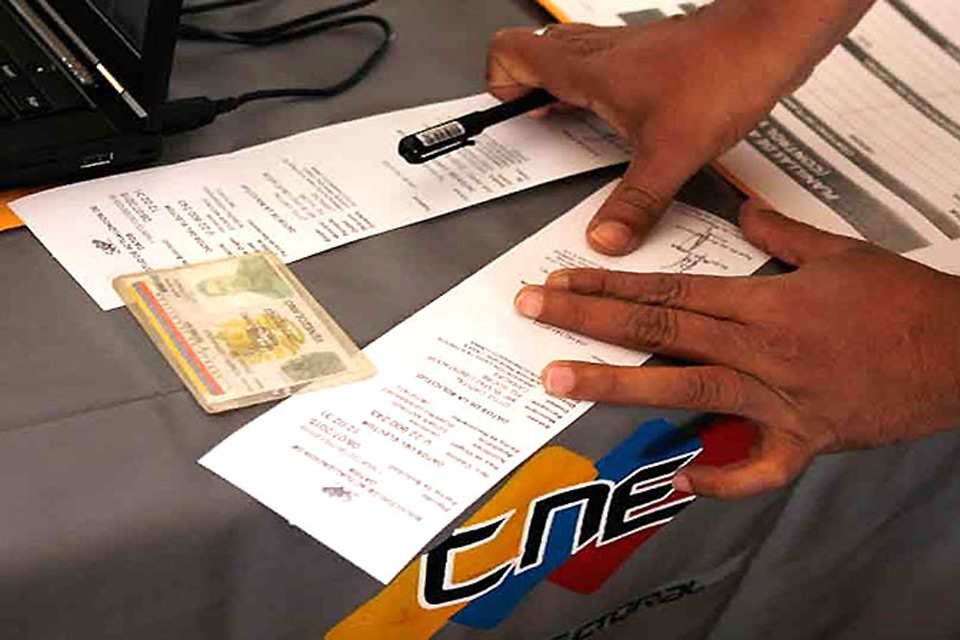

With the information recently received by the Ministry, Datysoc, composed mostly of lawyers, prepared a report concluding that the lawsuit allowed it to verify that the Ministry of the Interior effectively carries out cyber patrols without a regulatory framework that guarantees the rights of the people whose data is at stake. This cyber patrol, distinguished from street patrols, has as its main objective the analysis of information from open sources, is carried out by unidentified agents, and is commonly applied to specific people in intelligence targets.

Open sources are freely accessible and, in the case of the Internet, include social networks, media outlets, blogs and data found on the deep web.

Cyberpolicing: Practices and concerns

The Datysoc report stresses that “the new findings confirm concerns” and that “it is urgent to establish rules to regulate these practices, as well as transparency obligations” to ensure that police procedures respect due process and international standards of legality, necessity and proportionality, avoiding mass and indiscriminate surveillance.

A paradigmatic incident that occurred on April 28 highlighted the problems of cyber patrols. That Sunday, a confrontation between teenagers near the Nuevo Centro shopping center, announced via social networks, led the director of the National Police to declare that the networks were being monitored to prevent future fights. This surveillance resulted in the arrest of a teenager identified as Dante, who was wrongly identified as the instigator of the confrontations. Prosecutor Mirna Busich based her request on an intelligence report, but it was the wrong Dante, an episode that the Justice Department later confirmed.

This case illustrates, according to Datysoc, “the crucial importance of having clear limits, rules and protocols for the police use of open source intelligence techniques.”

Datysoc considers that the validity of the second point of its request – on the conduct or approval of studies based on open source data – shows that these surveillance practices go beyond prevention and investigation to encompass the management of internal issues. It also regrets that the ruling prevented it from obtaining more relevant details about the rules, regulations and related studies.

Errors and demands for regulation in digital surveillance

During the process, the Ministry of the Interior defended the idea of not disclosing police methods and mechanisms for security reasons, to which Datysoc replied that such reasoning could lead to total opacity, leaving society unprotected from possible abuses of authority and human rights violations. The civil association maintains that the ministry’s statement is based on the erroneous assumption that disclosing details about police practices would put the population at risk.

The Judiciary, in first and second instances, partially upheld Datysoc’s position, forcing the Executive to respond affirmatively to certain questions, although it allowed the omission of other details, such as the agencies involved in cyber patrolling and the regulations that support these activities.

Datysoc argues that the requested information is of high public interest because it involves the use of technologies and techniques that are potentially detrimental to civil guarantees, increasing the State’s surveillance capacity and therefore requiring transparency in its use and application.

The Ministry also denied having signed contracts with private companies for data collection and analysis, which surprised Datysoc given the purchase in 2020 of a social media analysis software, suggesting the need for some kind of contract with the private company Analythic Technologies. This situation, for Datysoc, “would merit an explanation.”

In its report, Datysoc recommends that legislators consider the use of social media intelligence (Socmint) as a “special procedure” within Law No. 18,331 on Personal Data Protection, requiring prior judicial authorization and justification based on proportionality and necessity. It also proposes expressly prohibiting the indiscriminate monitoring of citizens and requires judicial authorization to appoint undercover agents.