Achieving the global commitment to end the AIDS pandemic by 2030 involves combating the inequalities and stigmas that have accompanied this public health emergency since its emergence 41 years ago, highlights the Dangerous Inequalities report, released this week by the United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) to mark World AIDS Day, celebrated today (1st). Experts and activists reinforce that, even with the advancement of available drugs, discrimination against vulnerable groups and people living with HIV reduces access to health, prevents early diagnosis and causes deaths from AIDS that could be avoided with treatment.

In a message released to mark the date of combating the disease, the secretary general of the United Nations, António Guterres, warned that the world is still far from eliminating AIDS by 2030 and said that inequalities perpetuate the disease pandemic.

“Better legislation and the implementation of policies and practices are needed to eliminate the stigma and discrimination that affect people living with HIV, especially those in vulnerable situations. All people have the right to be respected and included,” he said. .

According to Unaids, 38.4 million people were living with HIV worldwide in 2021. This number is greater than the population of Canada or the sum of all inhabitants of the states of Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais. In Brazil, the number of people living with HIV surpassed 900,000 last year, according to the Ministry of Health, and, of that total, about 77% treated the infection with antiretrovirals. The effectiveness of the treatment available free of charge in the country is reiterated by the percentage of 94% of people with an undetectable viral load among those who use drugs against HIV. When the patient undergoing treatment reaches this level of viral load, he stops transmitting HIV through sexual intercourse.

Since the beginning of the AIDS pandemic, in 1980, until December 2020, Brazil has had more than 1 million cases of the disease, which caused 360,000 deaths. The detection rate has been falling in Brazil since 2012, when there were 22 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. In 2020, this proportion had reached 14.1 per 100,000, which may also be related to underreporting caused by the covid-19 pandemic.

HIV or AIDS?

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is an infectious agent that can enter the human body through vaginal, oral, and anal sex without a condom; through the use of contaminated syringes and other sharp or perforating objects; by the transfusion of contaminated blood; and from an infected mother to her child during pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding, if preventive treatment is not carried out. When it settles in the human body, this virus has a prolonged incubation time, which can last several years, and its activity attacks the immune system, responsible for defending the organism. If this infection is not detected and controlled in time with the use of antiretrovirals, HIV can weaken the human body’s defenses to the point of causing Human Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS). Therefore, the acronym HIV refers to the virus, and the acronym Aids, to the disease caused by the worsening of the HIV infection.

The use of male and female condoms and lubricating gel are among the main preventive actions against HIV. Also available are Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP), which consists of using antiretroviral drugs to prevent infection if the person is exposed to the virus, and Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP), which can prevent infection if it is administered within 72 hours of exposure. Even in the case of using these prophylaxis, the condom remains important, as it also prevents other sexually transmitted infections, such as syphilis and viral hepatitis.

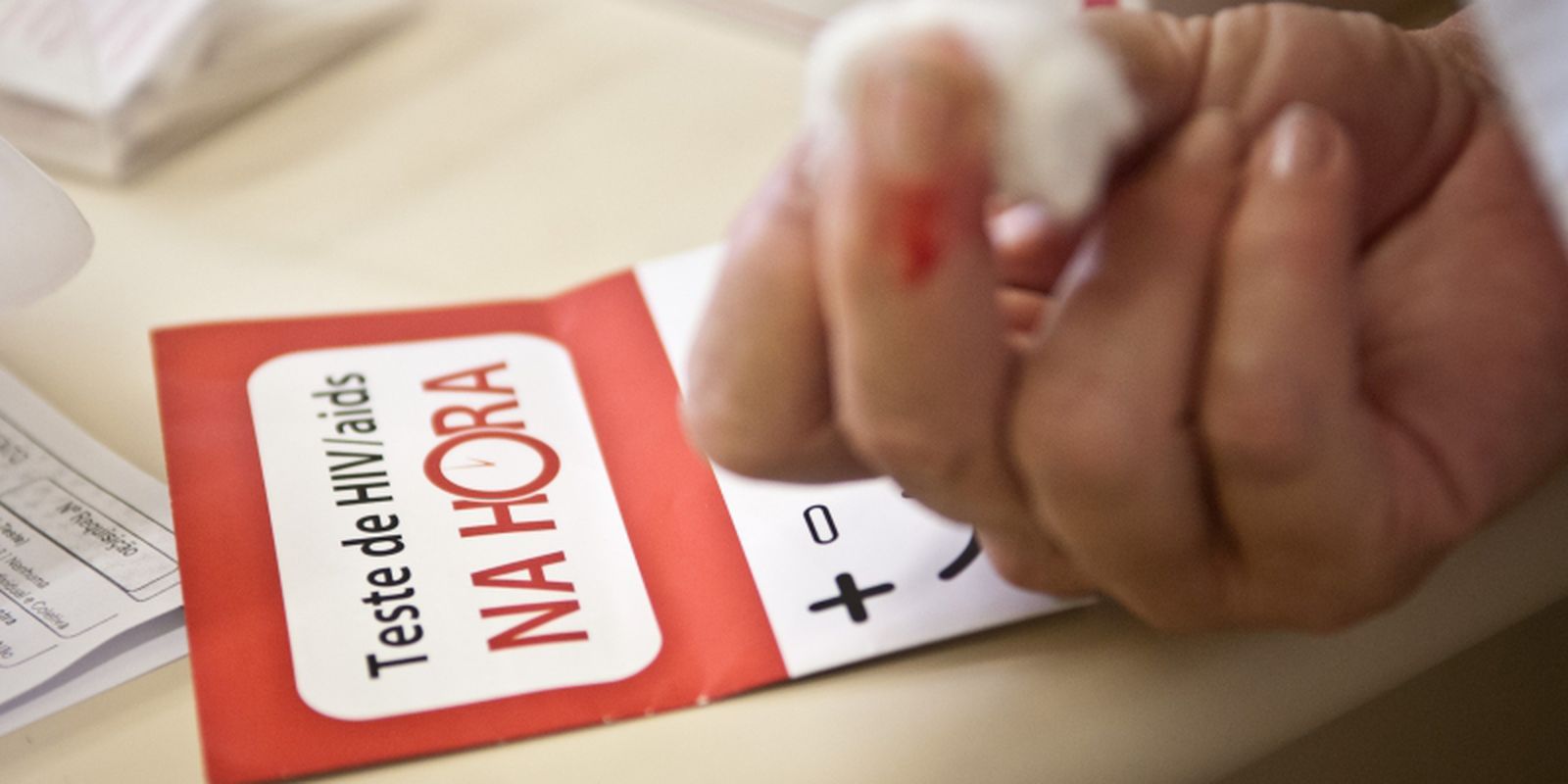

At least 30 days after a possible exposure to HIV, it is essential to take a test for the detection of the virus, an examination that can be carried out in public network units and in Testing and Counseling centers (CTA). Early diagnosis of infection and rapid initiation of treatment protect the infected person’s immune system, as this will be the target of HIV when the viral load increases.

Associate medical director of HIV at GSK/ViiV Healthcare, Rodrigo Zili explains that the antiretrovirals used today for the treatment of people living with HIV are less toxic to the human body, cause fewer side effects and are administered in much smaller quantities of pills. The pharmaceutical is the supplier of Dolutegravir and other drugs used in the Unified Health System (SUS) to fight the virus. Since 1996, Brazil has distributed antiretroviral drugs free of charge to all people living with HIV and in need of treatment, currently having 22 drugs in 38 different pharmaceutical presentations.

“The treatment today is much less toxic. We don’t even use the word cocktail anymore, because it’s not a huge set of medicines like we used to have. And, if the person discovers HIV in time to not have developed immunodeficiency, he or she has a very high chance of having a totally normal life taking daily medication”, says the infectologist. He reinforces that the person with HIV can have an even greater life expectancy than people who have not been infected by the virus. “This person who is undergoing treatment is following practically all diseases. So she does checkups periodic exams, receive advice to maintain a healthy lifestyle, and end up being able to have a healthier life than someone who does not have HIV and does not undergo medical follow-up”.

Even with these advances in HIV treatment and the free availability of drugs, access to health is still marked by inequalities, ponders Zili. “As much as you have a 100% public program, access to information and services is not completely equal”, recalls the infectologist.

Social questions

The coordinator of the Pela Vidda-RJ Group, Márcio Villard, believes that the therapeutic fight against AIDS has advanced more than overcoming the prejudices that affect people living with HIV. Even with less toxic drugs and a longer life expectancy, social issues keep people with HIV away from a fulfilling life.

“When we talk about quality of life, we cannot only understand the therapeutic and biomedical issue. It is also necessary to understand the social issues that involve the person with HIV, because we still face many problems related to stigmas, prejudices and social exclusion that interfere with the quality of life”, he says. “What happens is that HIV always brings condemnation. Somehow, society will condemn you, either because of your lifestyle, or because of your sexual orientation, or because you belong to a certain group in society. escapes, even a child who is born with HIV will be stigmatized for it. Unfortunately, this scenario has not changed”.

The activist explains that the stigmatization of people with HIV has roots linked to LGBTphobia, since the first outbreaks of HIV occurred in the homosexual, bisexual and transgender population in the United States, and the press in the 1980s reinforced the association between the LGBTI population and HIV, calling AIDS even cancer gay??

“It started in the United States, spread around the world and ended up becoming a label. Here in Brazil, until last year, homosexuals could not donate blood, regardless of whether or not they had the virus”.

Pela Vidda-RJ was founded in 1989 by sociologist and activist Hebert Daniel and has been active ever since in the fight for the rights of people living with HIV. At 11 am today, the group will promote a public event at Praça Mauá, in downtown Rio de Janeiro, with the theme Living with HIV is possible. With prejudice, no. Among the main current demands of the population living with HIV, Villard says that there is legal assistance to guarantee social security and labor rights. Problems include selection processes that eliminate candidates who test positive for HIV, while such testing is prohibited by law in any admission, periodic or dismissal examination. In addition to these rights, people with HIV also seek non-governmental organizations to receive affectionate care.

“The biggest difficulty is still the issue of stigma. When the person has this diagnosis, he has difficulty dealing with it. And when you stand up for your family, work, and friends, you will face discrimination. There are rare cases in which the person manages to live peacefully, regardless of their serology”.

distress and healing

The difficulty of finding information and acceptance after the diagnosis was what moved the influencer João Geraldo Netto to share his experience on the internet since 2008.

“Initially, I spoke in a more hidden way, I didn’t specifically say that I was living with the virus. But then I felt the need to talk about it more openly. I found that, speaking, I cured myself in a way. I felt something very positive when he talked about the dramas, the fears I had of undergoing treatment, of dying, of getting sick. And I saw that it was very well received. This gave me strength”, he says.

The journalist adds that most people who come into contact on social networks are distressed, either because they believe they have exposed themselves to the risk of infection or because they have already received the diagnosis and are trying to deal with it. João Geraldo believes that the social weight of HIV distances people from testing and early diagnosis, because many do not see themselves as part of a supposed social group that could be infected and others prefer not to know the result of the test out of fear.

“The issue of prejudice is something so strong that it hinders taking the test, seeking help and treatment and prevents the person from taking the medicine every day. So the big problem with HIV today is no longer a clinical problem, it’s a societal problem,” she says. “The people who come to my channel the most distressed are those who have gone through a situation that they consider morally wrong and believe that it is a punishment for them. And the worst punishment they can think of is a disease like AIDS. So this is very painful, you know? Because you see that you are talking to a person who thinks that the worst thing that can happen in life is what you have”.

In his posts on social networks, the influencer comments on HIV and everyday topics and his personal life, such as travel photos, meetings with friends and declarations of love to his boyfriend. On one of his profiles, called Superundetectable, he leaves the following message: “Take a deep breath! There’s still a lot of world ahead. Now it may not be, but everything can be fine.”