Holguin/The morning advances along the Valley road with an unforgiving rattle. Every pothole forces us to slow down, every puddle – thick, greenish – reminds us that last night’s rain found no drain or official rush. Electric tricycles, motorcycles, bicycles and private cars arrive here with the same destination: the Lucía Iñiguez Landín Clinical Surgical Hospital. People get off with fever, with joint pain, with the fatigue of someone who has been waiting for days for the body to relax.

“This feels like a test before you get to the doctor,” says a woman holding her sweaty son while dodging the pooled water. Arboviruses have once again put this road at the center of Holguín’s daily map: patients from Velasco, Gibara, Calixto García, Cacocum and the city itself cross this stretch punished by laziness and lack of investment to seek diagnosis and relief.

A few kilometers away, the scene changes color and texture. On the extension of Frexes Street, in front of the Provincial Assembly of People’s Power, the asphalt looks almost impeccable. There are no puddles, the cracks have been sealed, the curb is freshly combed. “Around here there are always cars of officials who come to meet every day; they don’t resolve anything, but they don’t stop holding meetings,” complains the driver of an electric tricycle while comparing, without raising his voice, the smooth pavement with the one he has just left behind. The illusion lasts just about 200 meters, from Bim Bom to a guarapera: just the stretch visible from the windows of the official building and the most traveled by those entering and leaving the offices of power. Beyond, the city returns to what it always was.

/ 14ymedio

The contrast is not just aesthetic; It is functional and symbolic. On the hospital road, puddles become traps for tires and ankles; The dust rises when the sun shines and the rain is absent, and when the downpour falls the mud gains ground. A cyclist brakes hard to avoid falling into a makeshift ditch; A driver of an old Lada calculates where to pass without leaving half a suspension in the attempt. “They don’t come here to look,” summarizes a neighbor who sells coffee on the corner and sees the caravan of sick people passing by every day. “If they came, this would already be fixed.”

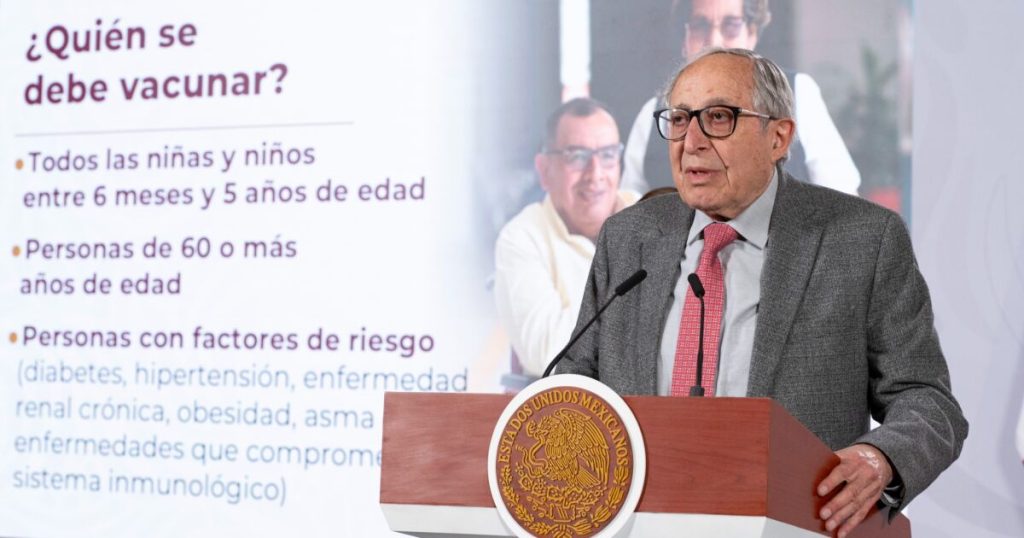

The photos tell what custom normalizes: in front of the Government, a continuous, clean floor, with fluid traffic; heading to the hospital, chained potholes, puddles that reflect tired facades, crumbling containers. On peak days due to dengue or chuukunguña, the road becomes an emergency funnel. The noise of the engines mixes with coughing, with the rubbing of wet sandals, with the hurried scolding of someone who is late for a consultation or the Guard Corps.

In Holguín, as in so many parts of the Island, the pavement also votes. Where there is power, there is paint and splash; where there is pain, there is waiting and damage. The Valley Highway does not ask for speeches or inaugural ribbons: it asks for drainage, asphalt, maintenance. Meanwhile, the way to the hospital will continue to be an uncomfortable anteroom to the disease, and the front of the Government, a polished postcard for those watching from above.