Theft and vandalism in the hermitage of the Potosí of Guanabacoa leave material damage, desecration of tombs and the discontent of the community in the absence of the authorities.

Havana, Cuba.- In recent days a new act of vandalism and robbery was confirmed in the emblematic hermitage of Potosí, located in Guanabacoa, Havana. As reported by the parish priest of the Miraculous of Guanabacoa on September 21, through a message loaded with regret and frustration, this would be the seventh attack on the chapel.

The ravages this time are numerous. They destroyed a window whose wood was already in a deplorable state due to lack of maintenance, they found garbage at the entrance and dispersed through the temple, dead animals, including chickens and a turtle. Tombs and a commemorative tarja linked to a pronouncement against slavery happened on the site more than three hundred years were also desecrated.

As if that were not enough, they defined inside, which aggravated the sorrow and humiliation of the jealous community of that sacred place.

In addition to the material and symbolic damage, the theft of religious objects and essential use was confirmed: the altar candelabra and the water pumping system engine were taken.

The incident has deeply shaken the local clergy and the faithful, who today express their outrage at the lack of protection and response of the authorities.

According to the parish priest, the police would have dismissed a similar complaint the previous week, after a visit of the Fermín deacon and another representative of the parish due to the successive robberies and acts vandalism in Potosí and in other religious real estate and of patrimonial interest of Guanabacoa.

“The police referred us: ‘The dead man was removed,” he said. Therefore, on this occasion, members of the community went to the Heritage and Religious Affairs offices, seeking that the authorities pronounce and act firmly. However, they also did not obtain a convincing response beyond the routine notification that they will open an investigation.

The situation in the Hermitage of Potosí not only reflects the physical abandonment of the place, but also the institutional carelessness that affects so many religious real estate in the country. While the community tries to preserve the spiritual and historical legacy, insecurity, vandalism and neglect threaten to erase centuries of memory.

The hermitage of Potosí and its architectural, religious and cultural value

Located at the angle of the streets of Potosí and Calzada de Guanabacoa, and protected by the gates of the old Guanabacoense cemetery, the hermitage of the Immaculate Conception and the Holy Christ of the Potosí, or simply hermitage of the Potosí, is the oldest Catholic building of the well -known Villa de Pepe Antonio.

According to the historian Guanabacoense Pedro Herrera, the first news of his existence dates back to 1641 when Doña Juana Recio, fourth possessor of the first mayorazgo founded in Cuba in 1570 by Antón Recio, and wife of Don Martín Salcedo de Oquendo, obtains the authorization to build in the Estancia El Potosí, in the town of Guanabacoa, a hermit Virgin Mary.

Originally of Table and Guano, it was inaugurated in 1644. According to some records, after repairs and remodeling with masonry, mammount and a Mudejar alfarje roof, covered with clay tiles, in 1675 it acquired the form that it maintains until today, as can be read in a Latin inscription on the door of the temple. Therefore, this building is remarkable. Among the contemporary ecclesial temples and constructions, Consider the only one that with greater cleaning retains the codes of religious architecture of the seventeenth century; It is also the only one built and consolidated in that same century, since the rest, although they are from the seventeenth, consolidated in the 18th.

The famous cycle of October 1846 caused considerable damage to the building, so it was subjected to a general repair that included the construction of an altarpiece with brick and plaster columns and two side rooms: one for sacristy and one for housing of the chaplain.

For that date, in a land adjacent to the hermitage the cemetery that since then covers it and that is known as the old cemetery of Guanabacoa was established. Although the first burial dates from the second decade of the nineteenth century, the tombs inside and the patio of the hermitage are much older.

Survivor three centuries and after having passed through a few restorations, the Hermitage of Potosí crossed the threshold of the new millennium in an alarming state of deterioration that prevented the realization of the cult, despite having been declared a national monument in 1997. Fortuna, however, came from outside.

Thanks to the work of the Cuban Catholic Church and the economic contribution of a German Catholic organization and not to official Cuban organizations – as emphasized This note of Cubanet-, the hermitage was saved from being in the ruins and in oblivion. After a great general repair, he reopened the public on December 12, 2004.

Beyond its material value, the hermitage represents the living memory of the religious and cultural traditions of the community. It is a spiritual symbol for the inhabitants of Guanabacoa, associated with devotional practices, local legends and the sense of belonging. Its permanence in the same place since the seventeenth century reinforces the connection between generations and the historical identity of the territory.

As is often the case with many places of worship, the Potosí hermitage is also associated with a founding myth that has gone from generation to generation until it becomes a legend.

Since its foundation in 1554, Guanabacoa had been designated as “people of Indians”, to concentrate there the natives and their descendants who survived the colonial extermination and that wandered by Havana in bad conditions. They were going to allow them, then, to exist, live, build their houses, cultivate their lands.

According to the tradition, in a hill near the hermitage, known today as Loma de la Cruz, lived an “Indian” called José Bicat. This “Indian” around 1660 would have donated to the hermitage a picture of Jesus Nazareno with the cross, in oil on Cedro, which he had acquired on a trip to Havana. A short time later, the painting reached as much fame that the hermitage ended up being popularly identified as the Holy Christ of Potosí.

Years later, the image would be claimed and transferred to another temple of subsequent construction, in the same Guanabacoa, but of greater relevance. Given this fact, Bichat was made of a copy of the original painting and placed it again in his beloved hermitage, which guarded with Christian suspicion and fervor. Both pictures, both the original and the copy that remains in the hermitage, are currently preserved.

In Guanabacoa, conceived to house natives, the Afro -descendant presence would gain strength very soon. This may explain why it was one of the first places of the Cuban nation where there was an anti -slavist pronouncement.

Precisely in the Hermitage of Potosí, the Capuchin priests Francisco José de Jaca (1645-1686) and Epifanio Morains (1644-1686) spoke against slavery in 1681, as a tarja of the National Committee “Route of the Slave” of the MONuments of Guanabacoa, which appears on this site. This tarja was outraged on September 21, when, for the seventh time, they broke into the hermitage.

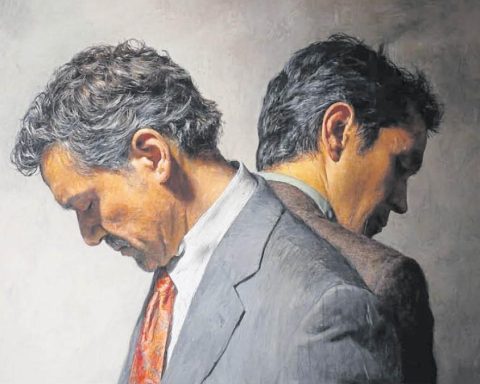

“It is a disrespect, but even more on the part of the government and the heritage people,” says Gloria, a Guanabacoense parishioner who, during the years in which the hermitage did not offer cult and remained under repair, housed in her home the images of saints, paintings and other objects of the temple. “It is very sad what is happening with the hermitage; it is again at risk of forgetting the abandonment and indifference of the authorities that must ensure this, the same ones that have designated the place as a monument. But if they are not interested in the people, what will care about a small church and old? What happens is that this is not any church, and they know it.”

For the Guanabacoan archivist A. Menéndez, the misery and the crisis of values have made people forget their customs and traditions and do not feel respect for anything. “People are concentrated in material needs, in their survival, because they have nothing … and see that the same institutions that should preserve and promote the care of these properties arehed their hands when acts like these happen; it is quite discouraging.”