May 17, 2024, 8:53 AM

May 17, 2024, 8:53 AM

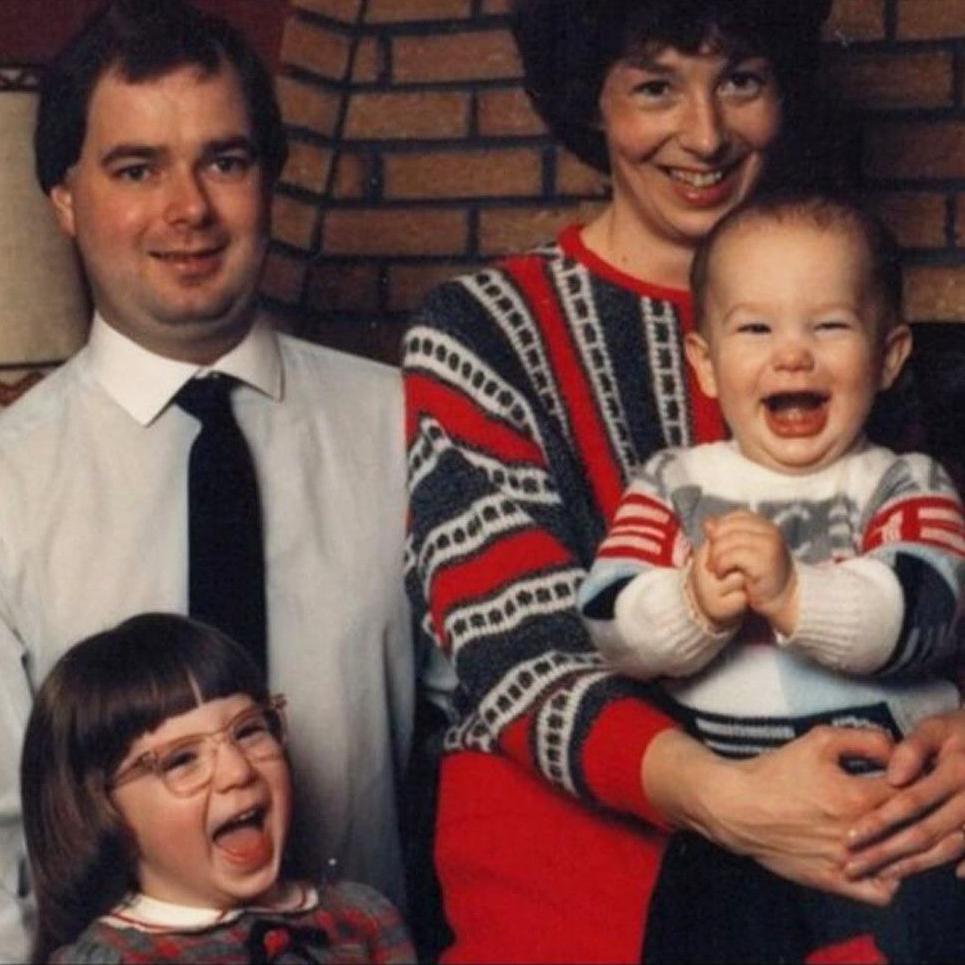

When John Jennings’ mother began showing signs of Alzheimer’s at age 50, he and his sister Emily knew they, too, would have a 50% chance of developing the condition that causes dementia.

But a letter his mother wrote almost 40 years ago could be the key to changing the future of his family and thousands of others.

“You often find older people who buy a pair of shoes and say, ‘Those are going to be with me forever.’ Basically, I’ve always had that attitude,” says John Jennings, 39.

“I ask myself, ‘Should I buy a new laptop?’, because I’ve had Macs that have lasted me 10 years in the past.”

John, who lives in Edinburgh with his husband Matt, is not concerned about material possessions because he does not know if he has inherited a defective gene from his mother that could cause early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

“I just discovered that what makes me happiest is being surrounded by people who love me,” he says. “So we spend a lot of time building relationships and that seems to be the most satisfying part of life.”

But these social connections are the things John most fears losing if he has the genetic mutation and develops the disease at age 50, like his mother Carol did.

“I’m trying to learn a lot of languages and I exercise obsessively, and I know that for most people that would dramatically reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer’s,” John says.

“But the thing is, to me, it doesn’t make any difference.”

For most people, advanced age is the biggest risk factor for Alzheimer’s. Of every 100 people with this disease, less than 1% will have the hereditary form.

Genetic mutation

In the 1980s, Alzheimer’s disease was thought to have no family link, but when John’s grandfather, Carol’s father, and her four siblings were diagnosed with the disease in their 50s, Carol knew this could not be true. be a coincidence.

A new BBC documentary tells the story of how Carol, a teacher from Coventry, a city in the south-central United Kingdom, helped change the course of research into Alzheimer’s disease with a handwritten letter.

She had always tried to find solutions to problems, John says, it was “her way of getting some control of the situation.”

In 1986, Carol wrote to a team at University College London (UCL) who were studying the disease. By analyzing the genetics of her family, the team identified a gene in 1991 that was shared by all of her relatives affected by this condition.

A mutation in the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene for its acronym in English) made it accumulate too much amyloid protein in the brainwhich clumps together to form plaques and causes brain cell death.

Carol passed on to John and his older sister Emily, 42, a 50% chance of inheriting the mutation genetics that trigger early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

“If someone has the gene, they will develop the disease at around the same time as their relatives,” says neurologist Cath Mummery, head of clinical trials at the UCLH Dementia Research Center (University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust). ).

“So they are aware of the time bombespecially when they get closer to that age.”

“It’s tempting to think that if I find out I have it, Emily won’t, and vice versa,” John says. “But it could be that we both have it. It could be that neither of us has it.”

To know or not to know?

For those at risk for genetic Alzheimer’s, a blood testto see if the genetic abnormality that causes the disease is present.

John’s mother Carol decided not to get tested because she believed there was no point in worrying, John explains, but while he respects his mother’s choice, it is not the path he wants to follow.

“We could have planned better if we had known she had it,” he maintains.

He was 21 years old when his mother first began showing symptoms in the mid-2000s. Her condition slowly deteriorated until she became bedridden and unable to speak.

Each stage of her mother’s decline was “like a new ton of bricks to deal with,” she says.

Carol passed away in March of this year. She asked that her brain be donated for scientific research.

John says he will definitely get the blood test done at some point and will decide when with his sister. Now it’s not the moment.

“I think if one of us got tested, the other would probably quickly do the same,” John says.

“So it almost seems like it’s a decision we must make together“.

The only thing that could speed up John’s decision to get tested would be if he needs this information to begin medical treatment.

Treatments

John is optimistic about new Alzheimer’s drugs that could be approved this year. These were designed for help the immune system remove amyloid from the brain and delay progress of the illness.

It has potentially serious side effects and its effectiveness depends on early diagnosis, so it is still early to know what impact they will have.

While hereditary Alzheimer’s disease is rare, it is similar in many ways to the more typical Alzheimer’s disease that develops in other people later in life, Mummery says, and can be used as a model for finding new therapies.

“If we can find a treatment that works for this genetic form, then we could extrapolate it to a treatment for the more common non-genetic form of Alzheimer’s disease,” he says.

This all grew out of the work Carol started with the UCL team, Mummery recalls.

While work continues to develop treatments, John’s coping mechanism is to stay strong and have a positive attitude.

She also recommends sharing experiences with other people in support groups.

He continues his mother’s legacy and helps change the course of the future by participating in Alzheimer’s research and receiving regular brain scans.

John says he feels we are “on the verge of seeing treatments that can help stop the disease in its tracks.”

“I’d really like to live long enough to see that, and I think I could.”

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and activate them.