Atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO₂) concentrations reached a new record in 2024, according to the latest report from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Global average surface concentrations of major greenhouse gases reached record highs last year, with carbon dioxide at 423.9 parts per million (or ppm), methane at 1,942 parts per billion (ppb) and nitrous oxide at 338 ppb.

In the 1960s, CO₂ was accumulating in the atmosphere at a rate of 0.8 parts per million each year (that is, annual increases of 0.00008%). This growth tripled between 2011 and 2020, reaching 2.4 ppm annually. And the growth rate of carbon dioxide between 2023 and 2024 has risen to 3.5 ppm, the largest annual increase since modern measurements began in 1957.

Before letting ourselves be carried away by the tremendism, it is worth immersing ourselves in this data and diving until we understand the causes of these increases. We will encounter several pleasant surprises that will remind us that we can still mitigate climate change and combine economic growth with decarbonization.

The economy is decarbonizing

The increase in CO₂ concentrations depends on the balance between emissions and absorptions of this gas (the “sinks”). That is, concentrations can increase if emissions increase, or if the absorption or storage capacity of sinks decreases. Although it may seem difficult to believe, the truth is that the world economy is decarbonizing: we are increasingly producing with fewer CO₂ emissions.

Carbon intensity, that is, CO₂ emissions per dollar of GDP, reached its peak in 1920, and has been falling almost linearly since 1968. This tells us, on the one hand, that policies aimed at reducing emissions have failed: emissions began to decline decades before conferences such as the Rio de Janeiro (1992) and Kyoto Protocol (1997), and that decline has not accelerated despite countless climate summits. But there is also a positive reading: the decarbonization of the economy is an unstoppable reality, despite the obstacles that governments and denialist multinationals try to impose.

On the other hand, these data show that emerging countries can grow with much less emissions than a few decades ago. The United States, which has always been the main emitter, generated 1.6 kg of CO₂ for every dollar of GDP in 1917, when it reached its peak carbon intensity. However, China’s emissions record stood at 1.1 kg CO₂ per dollar in 1960, when it peaked. India, which appears to have reached its emissions growth ceiling for now, showed a peak carbon intensity of 0.73 kg per dollar in 1992.

This result is very important because it tells us that economic growth is increasingly independent of emissions, and that countries in the global south will be able to improve their living standards with fewer emissions than those required by rich states.

Why have emissions increased?

Under this reality, it is worth asking why carbon dioxide emissions have increased. Declines in carbon intensity will not impact emissions if GDP increases very quickly. That is, it is of little use if we emit less CO₂ per unit of GDP, if GDP does not stop growing. Emissions will only decrease if the decarbonization of the economy advances faster than economic growth. And although it is true that decarbonization continues at a slower pace than many of us would like, it is no less true that we have been on the unstoppable path of economic decarbonization for decades.

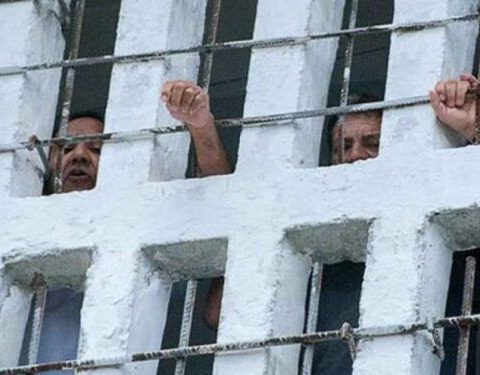

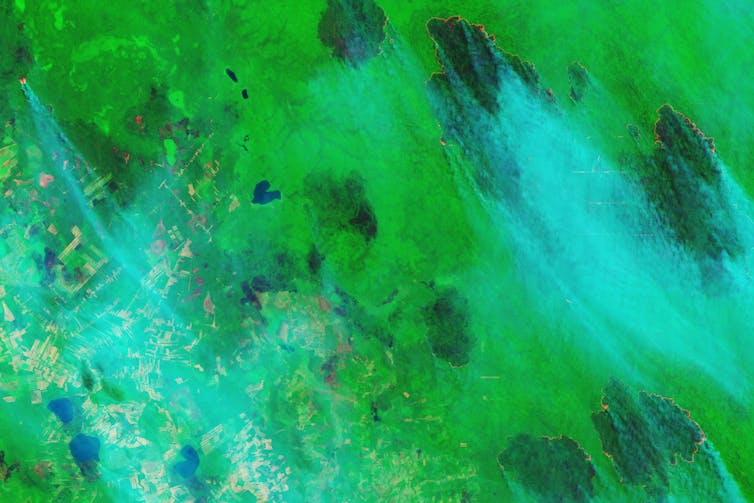

Now, the phenomenon that is shattering the emissions growth records, according to the WMO report, is not found in economic activity, but in fire activity. In 2023, Canada suffered the worst pyrus epidemic in its history, with 15 million hectares burned: the emissions associated with these fires were greater than any other country (except those of the three super-emitters: USA, China and India).

In 2024 we once again find ourselves with disproportionate emissions due to the many fires that affected tropical areas such as Brazil and Bolivia.

The fires in 2025 have also left us with record emissions in countries like Spain which, with an estimate of 19 million tons of CO₂ emittedis getting dangerously close to emissions from electricity generation (25 Mt).

Fires affect the carbon dioxide balance in different ways. The best known is the release of carbon stored in ecosystems. But the effects of megafires are felt for many years because they leave behind large areas of sparse vegetation and, consequently, areas where there is hardly any photosynthesis (the process by which plants absorb CO₂ from the atmosphere).

The conjunction between climate change and forest fires, therefore, is creating a dangerous loop: climate change favors megafires which, in turn, release colossal amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, increasing the intensity of climate change in a vicious circle.

The good news

The good news is that fires can be prevented. Years ago we warned of the advent of the age of fires that cannot be turned offdue to the increasing intensity of the fires. This phenomenon worsens year after year, but it can be avoided.

To do this, we need to manage around 5% of the forest territory. Forest science and engineering has shown us the way, which has proven its efficiency in many regions of the world.

The decarbonization of the economy is an essential step to reduce emissions, but the effort will be futile if it is not accompanied by large-scale management of the territory. Emissions induced by megafires are offsetting the improvements in carbon intensity that the global economy has developed over recent decades. Now we need to get to work based on harmony and evidence, replacing ideology with the scientific method, engineering and humanism.![]()

Victor Resco of GodProfessor of Forestry Engineering and Global Change, University of Lleida

This article was originally published in The Conversation. Read the original.