The taxation of 50% on Brazilian products entering the United States (USA) was the theme of the Measures of the Trump administration and the effects for Brazil, organized by the International Relations Council and the Superior Council of Economics, Sociology and Politics, Fecomerciosp.

The meeting, onlinewas held this Friday (1st), in São Paulo. For Fecomércio-SP, the measure is contrary to the basic assumptions of global trade, penalizing companies, job creation and economic growth in Brazil.

“The weakening of trade relations between the two countries compromises the willingness of business to invest, add value and expand their presence in the international market, and shake confidence between two nations, whose relationship is marked by the long tradition of commercial cooperation,” says the entity.

For Senior Economist and researcher at the Policy Center for the New South, Otaviano Canuto, with the measure, and already calculating the exceptions, Brazil should record reduced Gross Domestic Product (GDP) around 0.9% over a year. “In absolute terms, the impact is less than what would be with the 50% for everything. The impact is negative, but at the same time is not disastrous, except from the point of view of specific sectors such as meat and fruits.”

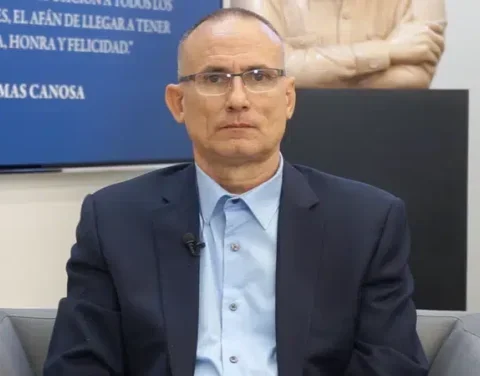

The sociologist and strategy director of the consultancy Arko Advice, Thiago de Aragão, noted that numerous companies are struggling to enter the exemption list. According to Aragon, negotiations actually start when the US publishes the list of exempt. “What is happening now is that we have industries trying to adapt to reality within the exemption list or an attempt to enter this exemption list.”

For the sociologist, sectors that have been out of the list can be included if negotiations are well conducted in the next 30 or 45 days. If this does not occur, the third alternative is to look for other markets. “At worst, there will be a decrease in investments if it is not possible to redirect production to the market that pay a similar amount.”

Aragon also said that the permanence of taxation for some sectors and products is strategic and that if the list comes out too perfect, the momentum of negotiation and the sense of urgency of Brazil decrease. He stressed that the way Trump establishes negotiations is not new and that there is always a political issue involved to press the other party.

“We can identify this pattern in several other negotiations. If in Brazil it is Bolsonaro and the Supreme; in Mexico, it is Fentanyl; in Canada, it is the issue of the 51st European Union, it is the attachment of Greenland; in South Africa, it is the opposite apartheid against white Africans; in Panama, the Panama channel. This political trigger is focused on generating anxiety. ”

According to the sociologist, in the letter sent to Brazil, this strategy is very clear, since the American points two types of dissatisfaction and an exit to solve them. “If the trade agreement is satisfactory, the other issues will be diluted, they will stop being structural themes in the relationship or negotiation. Trump likes to close deals, and his way of closing business is a zero sum.

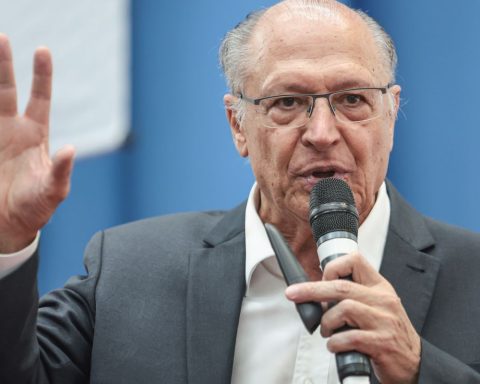

The president and founder of the Institute of International Relations and Foreign Trade (Irice), Rubens Barbosa, who was Brazilian Ambassador in the United Kingdom and the United States, stressed that, to resolve the current impasse without giving up sovereignty and preserving the 200 years of bilateral relations with the US, there is no alternative but to separate the political-diplomatic issue of commercial negotiation. For Barbosa, this is not happening.

“There is a contamination on commercial negotiation for the influence of US political measures. And I am referring to sanctions to the Supreme Court Minister Alexandre de Moraes. But, with the decision’s decision to ask the government not to make their defense abroad, it is easier for the government to focus its attention on trade negotiations.”

Barbosa points out that Brazil negotiates very well. According to him, Brazilian companies went to the US to talk to their American counterparts to press the local government due to their own interests. “And that was successful because it affected directly and positively close to half of exports, generating a partial relief of negative impact on the industrial and agricultural sector.”

About political-diplomatic climbing, Rubens Barbosa states that the government ‘needs to do something’. “It is not possible to spend eight months with the Boconist opposition in Washington, alone, talking to the US government all the time, without any participation of the Brazilian government to show that what was being said did not correspond to the truth, that the judiciary is independent, and all that we know.”