J

air Messias Bolsonaro was born on 21 March 1955. He presented himself as a (retired) army captain and throughout his time as a national deputy he incessantly praised his military training and his links with colleagues in uniform. He was elected president in 2018, defeating Fernando Haddad, the candidate for the Workers’ Party.

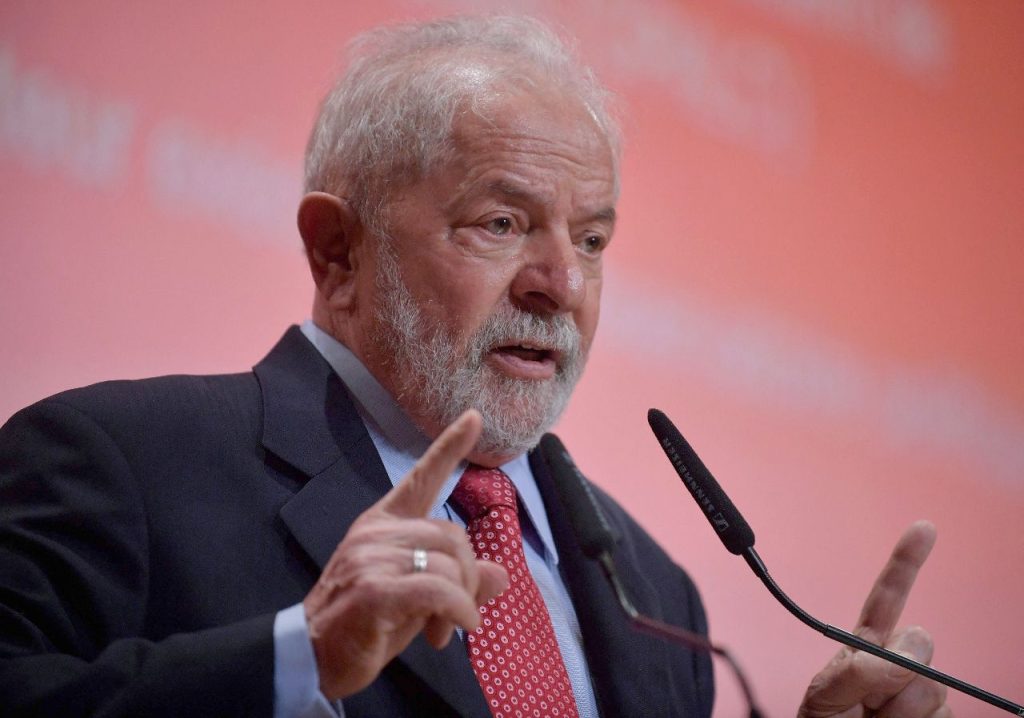

Haddad replaced Lula da Silva as candidate. The former president was detained as a result of the sentence imposed by the venal and manipulative judge Sergio Moro.

It was a landslide victory in the second round, with 55 percent of the valid votes against 45 percent for Haddad. And it was also the consequence of the intense process of demonization of traditional politics, initiated by Judge Moro himself, who would become Minister of Justice of the president he helped elect by arresting Lula, with the full support of the media, the business community and counting on the complicit omission of the Federal Supreme Court.

Bolsonaro, it is worth reiterating, insists on mentioning his military training and insinuating his ties with the army. He forgets an essential detail: he did spend 11 years in the army, but between his election as a councilman in Rio de Janeiro and his successive re-elections as a national deputy, it has been no less than 27 years. Almost three times as long as a professional politician than as an undisciplined military man, he served prison sentences in the army.

Throughout all his years as a national deputy he presented 169 bills. One –and only one– was approved. If today he is in his ninth political party, when he was a deputy he went through eight. Although this transit between parties is one of the absurdities allowed by Brazilian legislation, there are very few who transited as much as Bolsonaro.

Considered a very low level congressman, he became known among his colleagues for his aggressiveness, his misogyny and his rudeness. A brief selection of phrases said by him, in his Chamber times, reveal a lot about his personality and his way of seeing life.

Asked on one occasion how he would react if one of his four children fell in love with a black woman, he replied: There is no such danger, my children were well educated

.

When asked how he would react if one of his children were homosexual, he said: I prefer a dead son to a fagot son

.

In a discussion with the then deputy and former minister María do Rosario, of the Workers’ Party, he fired the phrase I don’t rape you because you don’t deserve it

.

At a press conference, when they wanted to know the reason for collecting housing assistance from the Chamber, despite owning a flat in Brasilia, he explained: I use the money to catch people

. The phrase, in addition to admitting diversion of public resources, was a frontal clash with the man who declares himself ultra-Catholic and conservative. The great defender of the family has such appreciation for the family institution that he was married three times.

In his time as a deputy he specialized – and later trained his children in this practice – in hiring ghost officials with resources from the Chamber. They were generally relatives of his second wife or militiamen

as hit men are called in Brazil, who kept at most 10 percent of their salaries and gave the remaining 90 percent to Bolsonaro.

He also used the rostrum of the Chamber to incessantly praise the military dictatorship that covered the country with darkness and victims of the colossal brutality of the regime between 1964 and 1985.

A tireless defender of the figure of Colonel Brilhante Ustra, a notorious torturer and rapist, he once admitted that the torture had been a mistake. And he clarified: Instead of having tortured a few, the government should have shot some 30,000, starting with Fernando Henrique Cardoso

.

Cardoso, exiled in times of dictatorship, was the president at the time.

There is a long, very long list of extremely absurd and abject acts and attitudes on the part of Bolsonaro. Once installed in the presidency, he made the worst government in the history of the Republic, harshly affecting or destroying all – absolutely all – sectors of Brazilian life.

That he has reached this October 2 showing, in his bid for reelection, around 34 percent of voting intentions according to the polls, only reinforces a doubt: what country is this?

To what extent does traditional ignorance, greatly promoted by the dictatorship, prevent a substantial part of the voters from seeing clearly the absurd aberration that is the figure that is trying to remain in power by way of the popular vote?