The art of Afro-descendant Cubans stars in the exhibition “El Pasado Mío/ My Own Past: Afrodescendant Contributions to Cuban Art”, which opens its doors this Friday at the Cooper Gallery of the prestigious US Harvard University.

The exhibition, which will remain on display until December 21, proposes, according to its organizers, “a new approach to Cuban art through a historical reconstruction built from and through the production of artists of African descent” . It aims to “highlight the racialized biases that have informed the traditional canon” and, as its title suggests, highlight the artistic contributions of a group insufficiently recognized and studied.

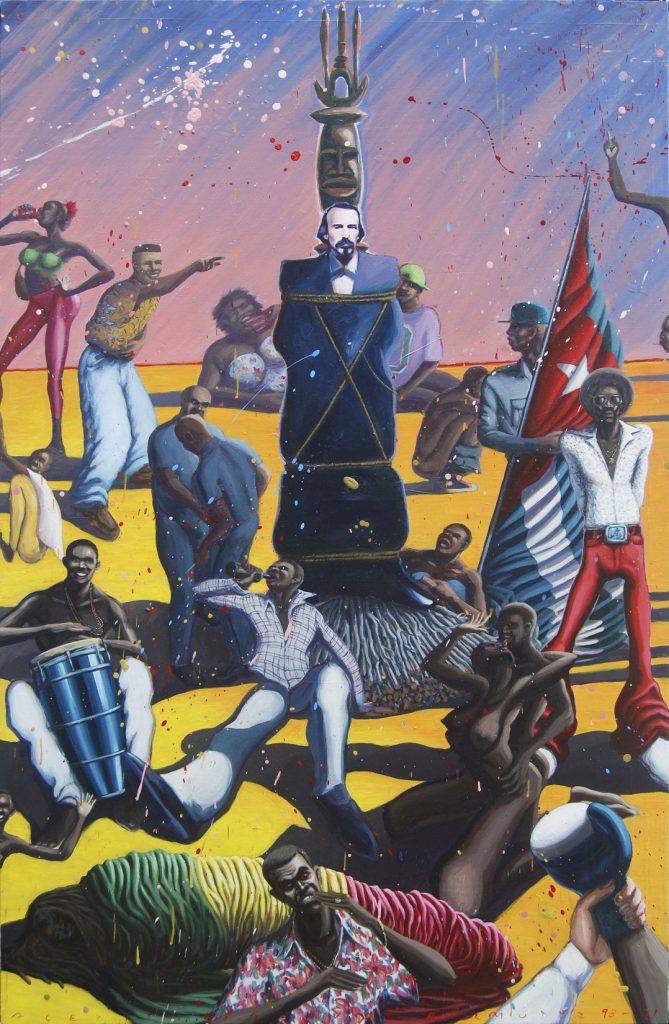

“El Pasado Mío / My Own Past”, according to the cover note from the Afro-Latin American Research Institute at Harvard University, shows “a group of artists who have never been presented together, including artists who have received little attention from art historians, critics and collectors.” The exhibition brings together more than 40 Afro-descendant Cuban creators from the colonial period to the present, from the pioneer Vicente Escobar to young people such as Susana Pilar Delahante and Carlos Martiel, passing through prominent figures such as Wifredo Lam, Agustín Cárdenas, Ruperto Jay Matamoros and Belkis Ayón, and others with much less recognition and visibility in academic and commercial settings.

Co-sponsored by Cernuda Arte and the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, it is “an unprecedented exhibition in Cuban culture,” according to Alejandro de la Fuente, Director of the Afro-Latin American Research Institute, a member of the team. curatorial of the exhibition together with Bárbaro Martínez Ruiz, from the University of Indiana; Cary A. García Yero, of the Free University of Berlin and the Leibniz University of Hannover; and Sebastián Pérez, from the Trinity School, New York. According to this prestigious Cuban professor and researcher based in the United States, “what ‘El Pasado Mío’ proposes is a new look at the history of Cuban art from the production of Afro-descendant artists.”

“In 1761, Martín Félix de Arrate, in his pioneering history of Havana, speaks of the ‘exquisite works’ created by ‘black and brown’ artists. Where are those works? Who are their authors? Why don’t we know them? And how is it possible that, after Vicente Escobar (1762-1834), we don’t have a single Afro-descendant painter in the entire 19th century?” asks De la Fuente in dialogue with OnCuba about the exhibition that opens this Friday at Harvard.

“When we focus on the production of artists of African descent, we glimpse a very different chronology of Cuban art. Traditionally, the history of Cuban art is linked to the creation of the San Alejandro Academy in 1818, which is presented as a before and after. The before is Afro and popular, the after is white and elitist. The Academy claims artistic production as a space for refinement, good taste and academic training, that is, as a white space. And it does so by eliminating, erasing, silencing the artistic production of Africans and their descendants”, he adds.

“And another thing, when one exhibits these artists together one realizes that it is impossible to pigeonhole them into one theme, style, or school. Their visual languages and contributions are multiple and diverse”, the specialist abounds, who did not want to fail to thank “those who in many ways have made this exhibition possible, especially private collectors who have given us access to their works. And especially to Cernuda Arte, without whose collaboration this project would not have been possible”.

What relevance do you give to the exhibition within Cuban culture, and in the vindication of the cultural legacy of Africa on this side of the ocean?

Efforts like this are not unique to Cuban culture. In the United States, museums and institutions of higher learning have come a long way in the process of rethinking art from African-American contributions. There are specialized courses, textbooks, collections, exhibitions. There have also been efforts in Latin America. In some way, our curatorial proposal is inspired by the pioneering exhibition that Emanoel Araujo did on Afro-Brazilian art in 1988. And of course, African contributions create continental spaces for dialogue and understanding. Africa is common to all the inhabitants of the hemisphere. Africa unites us.

What distinguishes, in your opinion, this exhibition from other exhibitions on the subject?

Unlike other exhibitions, which have focused on artists, groups, or specific themes, “El Pasado Mío” is conceived from questions of authorship. In that sense, it is an unprecedented exhibition in Cuban culture.

What paths or approaches to the subject could be opened from its exhibition?

One of our objectives is to highlight the need to carry out serious research based on new epistemological and theoretical assumptions about Cuban art. This exhibition allows us to highlight, first, how important the production of Afro-descendant artists is, their enormous weight in the art of the island, from the colonial period to the present. Second, it makes it possible to highlight the existence of numerous artists who are today forgotten, ignored, excluded. The official Cuban culture of the last sixty years has been a factory of forgetfulness that we need to dismantle. We want to draw the attention of young specialists, curators, museums and collections.

In the context of the exhibition, a panel with some participating artists is scheduled to take place on the 20th. What is the idea of it and how does it complement the show itself?

The round table with the participation of several artists from “El Pasado Mío” (Gertrudis Rivalta, Juana Valdés, Elio Rodríguez and Alberto Lescay), which will be moderated by me and by Bárbaro Martínez Ruiz, is an opportunity to listen to their perceptions, find out how they see the exhibition and its importance. In the exhibition there are artists from very different trajectories and stages; some very famous, like Wifredo Lam, and others barely known, like María Ariza. So, what does it mean for those who will participate in the panel to be part of a proposal of this type? How do you perceive your own work in that context? These are some of the questions we are interested in exploring.

Keep in mind that Cooper Gallery is an academic exhibition space, which means that numerous activities (conferences, workshops, debates) are always carried out around our exhibitions. But, the most important thing is the students, who write papers about it and are interested in these topics. An exhibition like this seeks to sow. They are seeds for the production of future knowledge. I wish we could do it in Cuba.