To be a painter with a military father at the end of the 19th century was more than a daring act, in the case of Munch (monk) it was an act of heroism. The illusionist Воронин (Varonin) would have given him his medal for a joking and eccentric magician.

It was crucial for Edvard that one of his sisters, Karen, pushed him into the world of art, more than his grandfather, who was also a painter.

To understand his work, it is not important to interview him to tell us his motivations, philosophy and other nonsense that “critics” invent because they don’t know what to talk about in the face of a work of vast creativity. It is as if they needed the script.

What does the interview with Oviedo tell us when he declared that he used red in his paintings because it was the color that sold the most? How does the interview with the sculptor Giacometti, who declared that he was not a sculptor, that he was experimenting with forms, help us? Because the work of art is a magic of human creativity that does not need an explanation, not even from its author… it is a language.

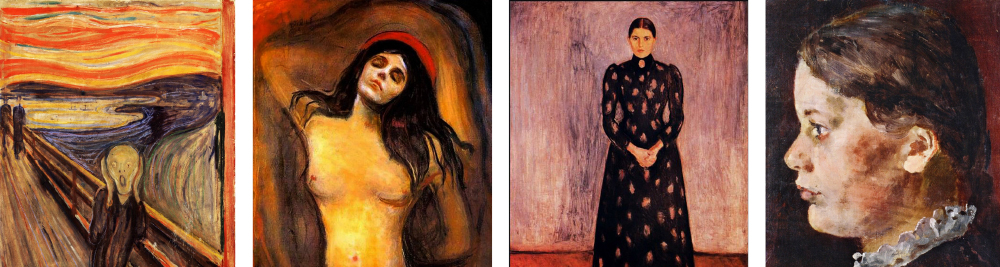

The only problem is that they want to force us to understand it and since that is impossible, everyone is left looking like ignorant idiots and they are the wise ones. Either we like it, or it touches us, or we are indifferent. And when faced with Munch’s “scream” no one can be ignorant, no matter how “ignorant” they are. The spectator simply captures what the artist transmits to them, and that’s it. If it is anguish, relief, denunciation, desperation… the public will judge it.

But there are others who are too wise and invent nonsense that has nothing to do with the artist and his visual production. How many imbeciles have not written that “the scream” represents an alien? And how many have not written about it without investigating, without ever having seen it, or knowing the life and work of the artist? Worse, they publish a “scream” that they grab from Google made by someone.

There are four versions of “The Scream”: two pastels from 1893, 1895, and two paintings from 1893 and 1910. The pastel drawing from 1895 was sold at public auction in 2012 for $119,922,500.

In 1892 Edvard Munch, aged 29, wrote in his notes:

“…I was walking down the street with two friends when the sun set. Suddenly the sky turned blood red and I felt a shudder of sadness. A wrenching pain in my chest. I stopped; I leaned on the railing, overcome with mortal fatigue. Tongues of fire like blood covered the black and blue fjord and the city. My friends walked on and I stood there, trembling with fear. And I heard an endless scream piercing the wilderness…

Those who write about art cannot understand any work more than what it reflects, and connecting it to movements does not solve anything since these are nothing more than periods of evolution to better study it.

Why does a “critic” need to know the emotions of an artist, since that does not contribute to unraveling the meaning of the work or anything else? If Da Vinci was drunk, widowed, bored, hungry, or a bird… what difference does it make to the outcome of his Mona Lisa?

The “critic” is not a painter, he is a writer and he should be writing. If he is inspired by the work of an artist, fine, but a critic of what? Is an artist going to listen to and follow his criticisms? A critic told me, fresh of course, that my signature was very big. What does it matter to him or anyone else how I make my signature?

Anyone would think that Edvard Munch painted only “the scream”, which, like “Gernika”, “The Mona Lisa”, or “The Thinker”, stand out in the production of their respective artists.

Norway, which together with Sweden form a peninsula that seems to be going to swallow Denmark, Germany and all of Europe, stumbled and made mistakes, like Berlin, which invited him to exhibit and which closed the show a week later for being “strange, repulsive… because his paintings were evil, ugly, full of obscenity and meanness, as Anton Von Werner declared.

Munch persevered and despite being classified as a degenerate artist by the Nazis, who also removed 82 works from their museums, he managed to establish himself like other “degenerates” such as Gauguin, Matisse, Klee and so many masters of universal plastic art.

And Oslo finally got it right. The Munch Museum, with its unusual architecture, presents all of his work: more than a thousand paintings, 4,500 drawings and watercolors and six sculptures.

There are many indicators to know if a town is cultured, civilized, advanced. It is not only the garbage, the bad management, the unbearable noise. And recognizing and valuing its artists is, without a doubt, one of them.

Why don’t we have a Yoryi Morel museum or a Tomás Hernández Franco museum like Jack London’s has in Sonoma, California?

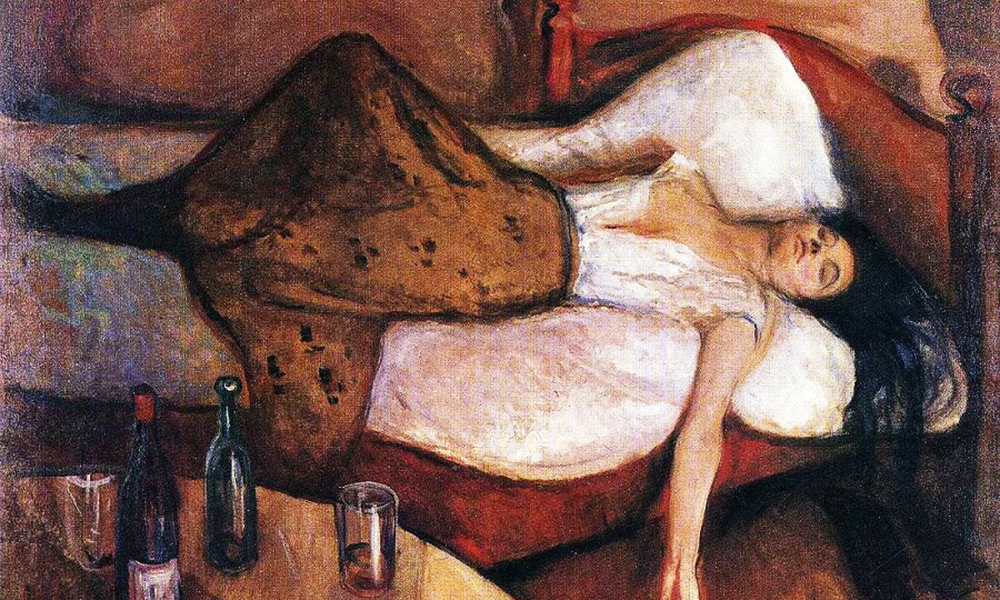

Living among his dead loved ones, his mother, his two sisters, a grandfather, his father, created part of Munch’s artistic mark. Many of his unique figures seem as if he himself had given them life, not only because he painted them, but because he brought them back from the grave.

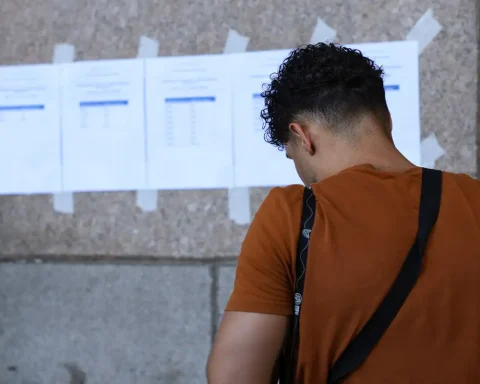

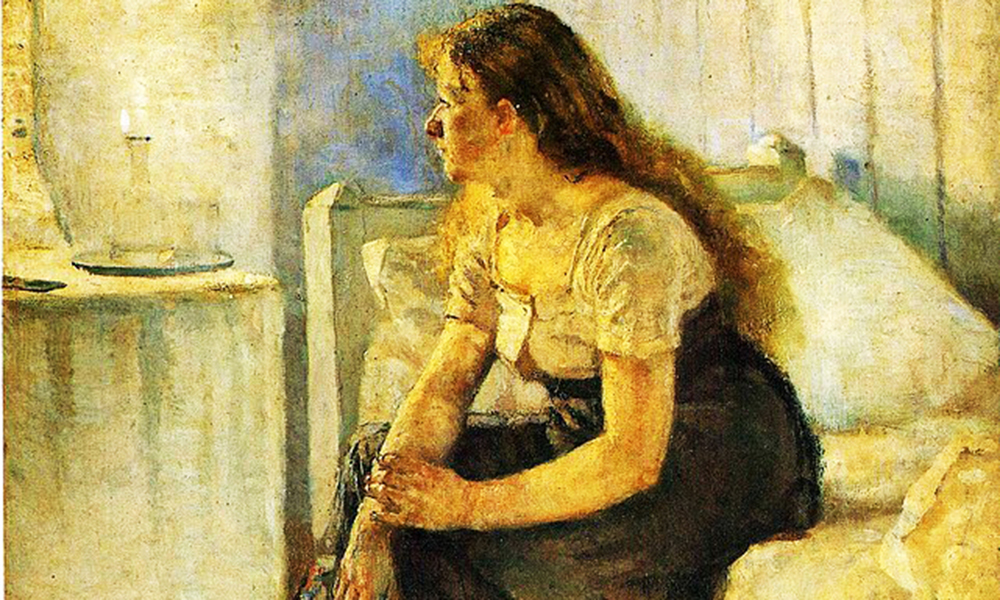

All his work was left in the shadow of “the scream”, his madonna, Inger, Laura, “morning”, the drunk or hungover woman from the day after, as if now his lovers and models and bohemian companions met, even if it was in Alan Poe’s Rue Morgue with crows, like mange, fluttering over the Museum.