Surrounded by fallen trees and limp cows, illegal rancher Chacalin surveys a clearing deep in one of Nicaragua’s largest remaining protected rainforests.

“When I came to this place, I knew that everything was reserved. (I told myself) I’m going to grab my tuco (piece) of land because I don’t buy it, I don’t pay. So that’s how we are doing it, ”he says before the camera with his head bowed. “If they take me out of here they can take my land, but I don’t lose money.”

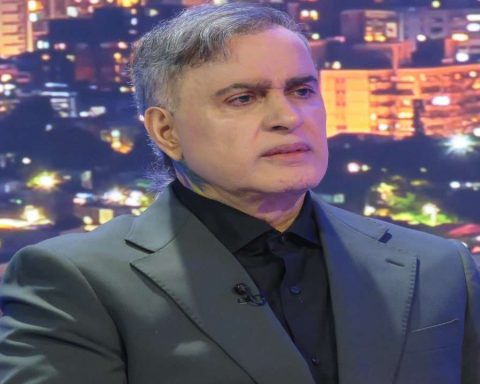

Since 2016 and for several years, the filmmakers Camilo de Castro and Brad Allgood visited the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve to make a documentary about the threats of deforestation and violations of indigenous rights.

Related news: Marena confirms cyanide contamination in the Tungkih river, in Bonanza, after a spill from the Hemco mining company

The approximately 2,600 square kilometer tropical jungle that extends into Costa Rica is a refuge of biodiversity and sacred home of the Rama indigenous people. But despite legal protections, it has seen more and more settlers arrive.

After the outbreak of the protests against the government of Daniel Ortega in 2018, which were violently repressed with a balance of more than 350 deaths, according to the UN, De Castro had to flee his country.

Since then, the situation in Indio Maíz (southeast) has only gotten worse, and the increasingly intense repression of opponents has made it too dangerous for filmmakers to return.

De Castro was one of 94 dissidents stripped of his citizenship by Nicaraguan authorities in February, along with his mother, the writer Gioconda Belli, and now lives in exile in Costa Rica.

Thanks to people inside the country sending them updates and pictures through the encrypted app Signal, the filmmakers premiered “Paw Patrol” on Friday at the Mountainfilm US documentary festival in Telluride, Colorado, hoping to bring the world’s attention to the situation.

“This is probably the last independent documentary to come out on Nicaragua in a long time,” De Castro notes.

“Basically, the government has put up a wall around the country so that people inside can’t hear anything coming from outside and can’t share information about what’s really going on in the country.”

“Colonization”

The documentary follows Rama Indians and Afro-descendant natives as they patrol their lands in canoes and on foot through the dense and treacherous jungle, dodging the fury of the rivers, dealing with ticks and jaguars.

It chronicles his encounters with ever-growing groups of recently arrived illegal settlers. Many work for wealthy ranchers who live off the reservation, paying them to cut down and clear the land before the cows arrive.

During filming, an indigenous patrol finds a large cattle ranch nestled in the middle of the reserve, and reports it to the police and Nicaraguan government officials.

Related news: Nicaragua, among the 10 “least green” countries in the world, with an accelerated advance in deforestation

The answer they receive is that they must pay if they want the police to investigate, while a meeting with a minister never comes to fruition.

Allgood believes that, unlike places like the sprawling Amazon jungle, Indio Maíz is a “small area” where “it would not be difficult to put up barriers to keep people out.”

But the government is “turning a blind eye: it’s in sight but no one is paying attention,” he says.

Meanwhile, the land conflict has escalated into violence, with settlers killing indigenous people, many of whom go unpunished.

“There is a lot of racism involved,” De Castro says. “I would say that we are filming the last stage of 500 years of colonization in Nicaragua.”

– “Respect the law” –

90% of deforestation in the region is due to illegal cattle ranching, according to Christopher Jordan, director for Latin America of the environmental organization Re:wild.

“Government corruption allows them to steal and deforest the land without consequences,” he denounces on the tape.

Beef is one of the biggest exports from impoverished Nicaragua, the United States’ sixth largest supplier.

A US law requiring beef to carry a “country of origin” label was removed in 2015, meaning consumers can rarely tell if their burgers or steaks come from animals raised on indigenous forest land.

While many importing companies claim to trace the origin of their meat back to the farm, De Castro and Allgood say this is not possible in Nicaragua, where the traceability process is too opaque.

“We talk about oil, we talk about mining… but the food industry is still not something that is getting enough attention,” says De Castro.

“What we want is for consumers to be more cautious, to ask questions when buying beef at the supermarket.”

As for the Nicaraguan government? “What we need is political will, so that they really make an example of some of these illegal ranchers and put them in jail,” he says.

“Once they put some of them in jail, people will think twice before going in. That’s what we want. We want the government to respect the law.”