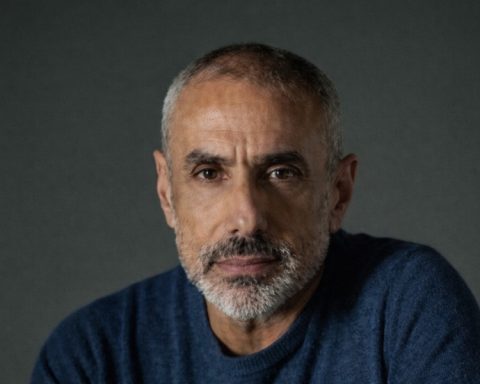

At the recent convention of National Partyheld last Saturday, the candidate for the Presidency of Uruguay, Alvaro Delgadopresented a series of proposals aimed at a hypothetical future government.

Among the proposed measures, one of the most striking was the initiative to award a “financial prize” to young people from the lowest socioeconomic levels who manage to complete their education in high school.

In his speech, Delgado stressed his intention to focus on “the two poorest quintiles of Uruguay,” focusing on the persistent problem of school dropouts in secondary education.

“It is a problem and it is a big problem. We cannot think of being a developed country and the most developed in Latin America if we do not change that paradigm and that figure,” Delgado said, reiterating his long-term goal of positioning Uruguay as the most developed country in the region, an ambition he has mentioned on previous occasions.

The former Secretary of the Presidency of the current government of Luis Lacalle Pou stated that this solution “has no precedents in Uruguay, but it does in some countries around the world.” The idea is to generate a system of economic incentives for young people belonging to the most disadvantaged sectors, specifically those in the first and second poorest quintiles.The purpose is to financially reward those who manage to finish high school, thus creating a strong incentive not to drop out of school.

Delgado did not hide the economic implications of his proposal, acknowledging that “it takes money, yes. Of course it takes money.” However, he firmly defended the idea, saying that “it is the best money invested of all.”

In his own words, it would never be seen as an expense, but rather as a significant investment and an opportunity to ensure that “there is not a single child in Uruguay who has not finished high school.”

During the convention, Delgado’s candidacy was also formalized along with Valeria Ripoll as a formula – approved with 441 votes out of 442 – and the government program for the period 2025-2030 was ratified unanimously. In his presentation, Delgado detailed several strategic axes for what he calls a “second floor of transformations.”

One of the axes of the speech focused on society and families, including the proposal to economically encourage young people from the poorest sectors. This approach also seeks to “Trying to halve child poverty in Uruguay in five yearsTo strengthen this objective, Delgado plans to invest US$200 million in early childhood education by the end of the next five years.

In addition, Delgado said he is committed to giving “priority” and “universalizing” access to full-time schools. His intention is to provide “opportunities from the start,” ensuring that quality education is not only distributed, but that it is accessible from the first years of education.

Orsi crossed Delgado: “Let them do it now that they are in government”

During a recent press conference, the candidate of the left-wing coalition Frente Amplio, Yamandú Orsiwas consulted about the proposal launched by Álvaro Delgado, representative of the National Party.

Orsi was quick to criticise the feasibility and timing of the proposal, given Delgado’s current position in the government. “Let them do it now that they are the government,” Orsi responded sharply, suggesting that the ruling parties have the capacity to implement these measures without waiting for a change of administration.

Orsi questioned the sincerity and timing of Delgado’s proposal. He stressed: “If he proposes it, it is because he knows the numbers and the costs involved. Someone who was in the Secretariat of the Presidency knows, so he should do it tomorrow, he should propose it to the president so that he can start now.” This strong statement points to a perception that promises made during election campaigns may not materialize if not addressed immediately.

In addition to criticism of the educational proposals, Orsi also expressed his discontent with the security policy suggested by the ruling party, specifically night raids. He described this measure as an “isolated solution” that, in his opinion, has a more electoral than effective purpose. “They smell more like marketing than anything else”he concluded, suggesting that these measures are used more as a campaign strategy than as concrete and effective solutions to persistent problems such as drug trafficking.

On the other hand, Carolina Cosse, vice-presidential candidate for the same coalition, focused on housing needs, highlighting that addressing this issue can also generate new employment opportunities. Cosse sees the problem of access to housing as an opportunity for economic development, suggesting that investment in construction can simultaneously provide housing and employment. “There we bring together a problem with an opportunity,” she said, suggesting a comprehensive approach to the development of the sector.

Cosse also stressed the importance of tourism in the north of the country, seeing in departments such as Artigas and Salto a potential that could be harnessed and promoted as part of regional economic growth.

In response to questions about policies to eradicate settlements, Cosse referred to the Frente Amplio program, which “marks a budgetary effort,” and called for further research into “tools such as cooperative housing,” which have proven effective in the past. Orsi complemented this reasoning by suggesting that budget reduction could limit progress in effective housing policies: “There is something that is on the cover of the book, if one cuts the budget, it is most likely that one will do less,” she said, criticizing what she considers a lack of concrete action regarding the promises made to citizens.

Delgado’s ideas are, according to him, innovative in Uruguay, but they have already been tested in other countries with mixed results and, in some cases, inconclusive results as to whether these projects are positive or negative.

The idea of providing financial incentives to students to complete their secondary education is not new and has been implemented in several countries with varying results. This type of programme, known as “conditional transfers”, has been tested with the aim of reducing school dropouts and improving access to education, especially among the most disadvantaged sectors.

1. Mexico – Opportunities/Prospera Program: One of the most notable programs is the one implemented in Mexico, which began as “Progresa” and was later renamed “Oportunidades” and recently “Prospera.” This program provided conditional cash transfers to low-income families, but on the condition that children regularly attended school and received medical care.

The most important problem that this program has encountered in Mexico, a country with almost 35 million students, is reaching the most remote places, as well as sustainability over time, which requires political transversality, in the sense that, from one government to another, the program must survive ideological differences.

In Brazil, the Bolsa Familia program phenomenon, established in 2003 by then-President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, has also had mixed results, with an increase in the school retention rate and a decrease in poverty. But when Jair Bolsonaro reformed it in 2021, renaming it “Auxilio Brasil,” he sought to expand benefits and update eligibility criteria amid the coronavirus pandemic. However, the scope did not grow and it continues to face some structural challenges that go beyond the mere intention of keeping students in school.

Maintaining the funding necessary to support the scope of the program has been a constant challenge, especially in contexts of budgetary constraints and economic fluctuations.

There have been cases of people taking advantage of the system by submitting false information to receive benefits, which requires strong control and monitoring mechanisms to prevent corruption among officials and beneficiaries.