Self-defense. Lack of evidence. Homicide without intent to kill. Common expressions in trials of police officers accused of murdering favela residents. In the end, the sentences are similar: the defendants are acquitted or the case is transferred to courts more favorable to the police, such as the Military Court. In 2024, in Rio de Janeiro, at least five high-profile cases had this type of outcome.

The most recent trial was that of teenager João Pedro Mattos Pinto. On the afternoon of May 18, 2020, the Federal Police and Civil Police of Rio de Janeiro carried out an operation in the Salgueiro community, in São Gonçalo, in the metropolitan region. João Pedro, then 14 years old, was at his uncle’s house and was shot in the back by a rifle. The house was left with more than 70 bullet holes.

The investigation found that the shot that killed the boy came from a police officer’s gun. The officers’ defense claimed that they entered the house to chase criminals during a confrontation. However, a witness said that he did not see any drug dealers at the scene. The Public Prosecutor’s Office stated that the crime scene was altered by the officers to simulate a confrontation.

In February 2022, agents Mauro José Gonçalves, Maxwell Gomes Pereira and Fernando de Brito Meister were charged with double-qualified homicide, for a vile and futile motive, and were responding at liberty. Until, on July 10, judge Juliana Bessa Ferraz Krykhtine decided to acquit the three, claiming that they acted in “self-defense”.

The sentence outraged João Pedro’s family, who sought out the Public Defender’s Office and the Public Prosecutor’s Office to appeal.

“The judge’s decision was absurd and disastrous. There’s no way a sentence like that could be handed down, which speaks of self-defense. Only the police fired shots. The police thought they had the right to invade a family home, where there were only teenagers playing, and they fired more than 70 shots,” said Neilton Pinto, João Pedro’s father.

“Going to a jury trial was the least that could have happened. But unfortunately, the judge only looked at the police officers’ testimony, which was all forged and concocted. There was no truth in it. Financial compensation is part of the process, but first the police officers must be held accountable for their actions. They took the life of a 14-year-old boy who was inside his home. They must answer, be arrested and expelled from the institution where they work. It’s the least they can do,” added Neilton.

Johnatah Case

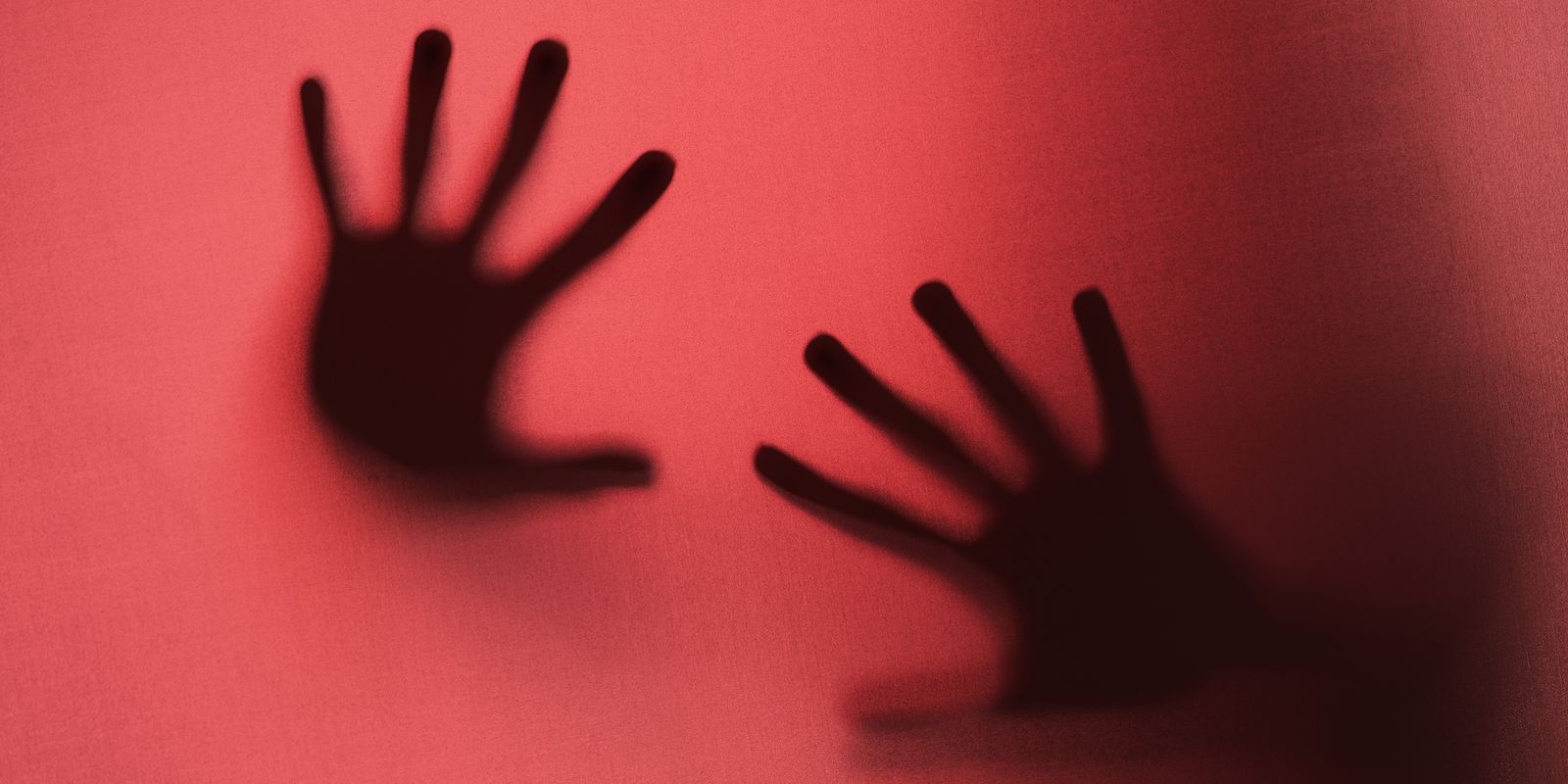

For the victims’ families, decisions in favor of the police trigger new forms of pain. When the crime occurs, they are struck by grief. After the trial, they feel discouraged and doubtful: “Was my struggle all this time in vain? The justice system also has its hands dirty with the blood of our children, spilled daily by the police in the favelas,” says Ana Paula Oliveira, mother of Johnatha, who was killed in 2014 by a police officer in Manguinhos, in the North Zone of Rio.

On March 6, the 3rd Jury Court of the Capital ruled that the murder of Johnatha de Oliveira Lima, in 2014, in the Manguinhos favela, in the North Zone, should be classified as manslaughter, when there is no intention to kill. The decision represents a lower classification than that requested by the prosecution, for which the crime committed by military police officer Alessandro Marcelino de Souza was a willful homicide (with the intention to kill).

The decision resulted in a decline in jurisdiction and the case was transferred to the Military Court for trial. The trial and investigations will resume and the sentence will be decided by military judges. The Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Public Defender’s Office appealed the decision.

Johnatha was 19 years old on May 14, 2014, when he came across a disturbance between police officers and residents of the Manguinhos favela. A shot fired by the Pacification Police Unit (UPP) officer, Alessandro Marcelino, hit the young man in the back. He was taken to the Emergency Care Unit (UPA) and died.

“We had witness evidence, expert evidence, and even a 3D video of a forensic examination was made, which disproved the police version of events. There was a lot of evidence. And even after 10 years, the witnesses were still willing to talk,” says Ana Paula.

And he adds: “the justice system mocks the pain of mothers who have their children murdered by state agents. I was in despair when I received this result. The police have the approval of the justice system. And the Public Prosecutor’s Office does not fulfill its role of externally monitoring police activities. I was in despair when I thought that other mothers would be in my place.”

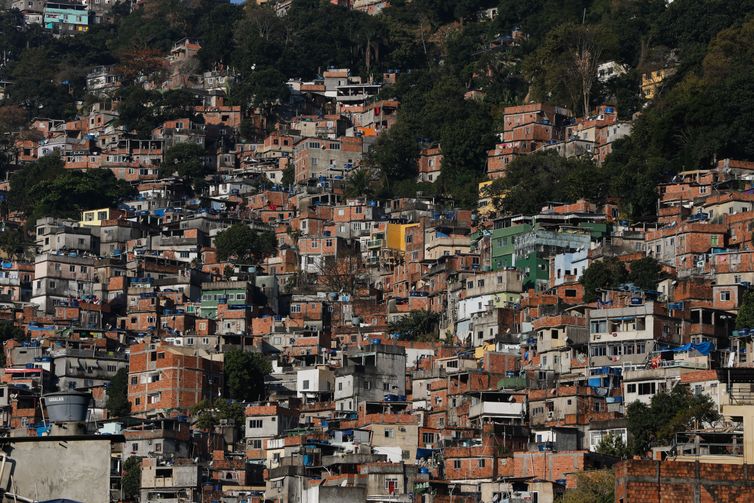

She continues by stating that “I do my job, but the Judiciary does not do its job. The justice system in Brazil is not equal for everyone. It is a racist system that only sees us when it is time to condemn us. Most of the people who sit in those chairs, as judges or prosecutors, are white, who have never lived the reality of a favela, who have never had a loved one murdered by the State. So, they cannot put themselves in our shoes. And what we see is the constant criminalization of the favelas and the people who live in them,” adds Ana Paula.

Dysfunctional system

Experts consulted by Brazil Agency argue that the recurring acquittal of police officers is part of a structural problem that involves different actors and instances of power that tend to privilege State agents.

“What normally happens is that the police kill, the police do not investigate and the Public Prosecutor’s Office does not carry out its constitutional duty to monitor police work. The few cases that reach the courts end up resulting in the acquittal of the defendants, because the investigations were not conducted efficiently,” says Carolina Grillo, sociologist and coordinator of the Study Group on New Illegalisms (Geni-UFF).

“Most of the time, the investigation ends up being carried out in a merely formal manner, with the purpose of gathering the necessary pieces of evidence for archiving. So, the medical report, the autopsy report, the family’s identification document and the victim’s criminal record are gathered. These cases are not investigated. The rare cases that reach the Jury Court are those in which the family members are able to gather evidence and there is greater repercussion in the press,” adds Grillo.

Poliana Ferreira, PhD in Law from Fundação Getúlio Vargas (FGV), with a research internship at Harvard Kennedy School, agrees that the issue of producing evidence and monitoring police work are fundamental.

“It is the police officers themselves who produce the evidence. We need to think of new institutional mechanisms that balance this process. We need to make sure that the narratives of victims’ families have a better impact in court. We need to rethink protocols and improve police oversight. One example is recording images on body cameras, but we also need to make it possible for these images to be accessed more widely and not just by the police themselves,” argues Poliana.

Even when cases are able to move forward and go to the Jury Court, the result can be unsatisfactory. This shows that the problem is even more complex.

“It is worth remembering the profile of the jurors. They are laypeople, who do not have technical or legal training, and generally corroborate the views of public opinion, of common sense, which tends to be lenient in relation to lethal police activity”, argues Carolina Grillo.

“The jury is not accountable for its decisions, unlike the model in the United States. In Brazil, jurors are asked to judge according to their conscience, but they do not record their arguments. There is no reason why any of them decided in such a way. And, at the end of the day, judges, lawyers and prosecutors participate in the selection of jurors. As a civil society, we cannot even make inferences about that jury,” explains Poliana.

Acquittals

Other cases that ended with the acquittal of police officers in 2024, in the State of Rio, were the deaths of Lucas Albino, Claudia Ferreira and Mães de Acari.

On March 11, the 4th Criminal Court of the Rio de Janeiro Court of Justice (TJRJ) acquitted four military police officers who were charged with the murder of Lucas Azevedo Albino, 18 years old. He was killed at an entrance to the Pedreira Complex, in Costa Barros, in the North Zone, on December 30, 2018.

Police officers Sérgio Lopes Sobrinho, Bruno Rego Pereira dos Santos, Wilson da Silva Ribeiro and Luiz Henrique Ribeiro Silva were charged in July 2021. Three years later, they were reinstated and returned to their police duties. In his decision, Judge Gustavo Gomes Kalil stated that they fired in “self-defense” and alleged a lack of evidence to incriminate them for the shot that hit Lucas in the head. The Public Defender’s Office appealed the decision.

Lucas’ mother, Laura Ramos de Azevedo, investigated the crime on her own. Among the evidence collected, she found a witness and a photo that reinforced the argument that Lucas was placed in the police car without any head injuries. This led to the accusation that the police officers executed him. But Laura did not live to witness the trial. She died of cancer in 2023.

On March 18, the Rio de Janeiro Jury Court acquitted six military police officers involved in the death of general services assistant Claudia Silva Ferreira. She was killed in 2014, near the house where she lived in Morro da Congonha, Madureira, in the North Zone. A video captured Claudia’s body being dragged for about 300 meters by a Military Police vehicle during an alleged rescue attempt.

In his decision, Judge Alexandre Abrahão Dias Teixeira stated that there was self-defense and a lack of evidence regarding the authorship of the shots that hit Claudia. Officers Rodrigo Medeiros Boaventura and Zaqueu de Jesus Pereira Bueno were acquitted of the crime of homicide. Adir Serrano Machado, Alex Sandro da Silva Alves, Rodney Miguel Archanjo and Gustavo Ribeiro Meirelles were acquitted of the charge of procedural fraud, for having removed the victim’s body from the place where she was shot.

On April 5, 2024, the Sentencing Council of the 1st Jury Court acquitted due to insufficient evidence the four defendants accused of involvement in the deaths of Edmea da Silva Euzébio and her niece, Sheila da Conceição.

Edmea and Sheila were shot and killed on January 19, 1993, in the parking lot of the Praça XI subway station, in downtown Rio. Those accused of the crime were Eduardo José Rocha Creazola, Arlindo Maginário Filho, Adilson Saraiva Hora and Luis Claudio de Souza.

Edmea was one of the leaders of the movement that became known as Mães de Acari, formed by mothers of 11 young people from the Acari Favela, who were kidnapped on a farm in Suruí, a neighborhood of Magé, in the metropolitan region, in July 1990. They were never found.