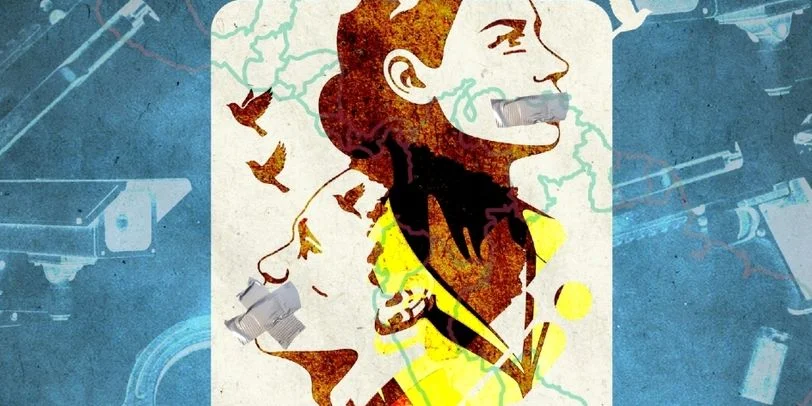

The University of Costa Rica alerts in a report that Cuba is among the three most repressive countries for the press in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Miami, United States. – Cuba is among the most hostile countries for the exercise of journalism in Latin America and the Caribbean, according to the report Displaced voices: perspectives of forced displacement of journalists and human rights defenders in Latin America and the Caribbeanpublished by the University of Costa Rica this month.

According to the document, the island concentrates together with Venezuela and Nicaragua “92.31% of the total cases of displaced journalists documented between 2018 and 2024”. In that period, 477 cases were recorded in Venezuela, 268 in Nicaragua and 98 in Cuba.

The research was coordinated by the program of freedom of expression and right to information (PROTE) of the University of Costa Rica, and analyzes the factors that promote the displacement of journalists and human rights defenders in 15 countries of the region.

One of the central findings of the report is that in countries such as Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela “persecution and stigmatization is led by the Executive Power.” According to the researchers, “the heads of state openly attack the independent press, which facilitates the use of state institutions to harass and criminalize the press.”

The report emphasizes that the forced displacement in these contexts responds to patterns different from those of countries such as Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras or Colombia, where the violence of non -state actors – such as organized crime – is usually the main cause. In contrast, in Cuba, repression is eminently state.

On the methods used to suppress journalists in Cuba, the document details that on the island “the visits of public officials who directly ask the journalist to leave the country under the threat that, if he does not, will be investigated and eventually imprisoned.”

This type of forced exile, highlights the report, occurs frequently abruptly: “In the case of Cuban, Nicaraguan and Venezuelan journalists, there are no longer even a prior exit planning; this occurs immediately and without minimal security conditions.”

The chapter dedicated to the profile of displaced persons also indicates that, although the reasons for exile may vary, in authoritarian contexts such as Cuban, “the main reason is direct harassment by public officials.”

One of the most serious consequences identified by the authors is the loss of generational relay in independent journalism: “Forced migration is generating a kind of extinction of institutional journalism.” In many cases, the media lose their most experienced journalists and, with them, their networks from sources, their local contacts and their ability to analyze.

Likewise, the report warns about the impact that the displacement has on the informative ecosystem of the countries of origin: “most fail to continue exercising their work and this has resulted in areas of silence and informative deserts.”

The document also describes the challenges that journalists face in exile, including “the difficulty in sustaining the media, to obtain financing, to achieve statements, to receive and verify information, to validate their contents on new platforms and to adapt to new legal frameworks.”

In its conclusions, the University of Costa Rica warns that “it is urgent to recognize forced displacement as a serious violation of human rights and adopt mechanisms for protection, attention and repair.”

The receiving states are also urged to facilitate “access to safe migratory status” and “the creation of psychosocial and economic accompaniment programs for displaced persons.”

Finally, the document closes with a call to action: “We hope that this work will contribute to the debate on journalists forced to displacement in our region” and that serves “as an input to continue defending the rights to freedom of expression and press, as well as the fundamental principles of democracy and human rights.”