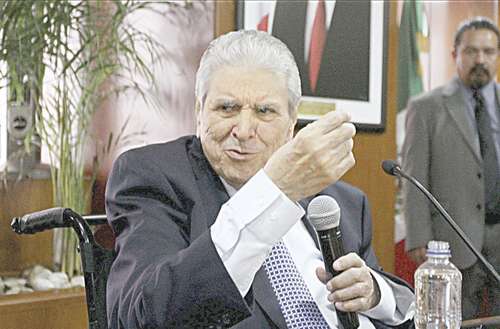

▲ The central led by Carlos Aceves del Olmo has avoided direct confrontation with the presidential power.Photo Maria Luisa Severiano

Arthur Cano

Newspaper La Jornada

Monday, June 20, 2022, p. 4

Barely uncovered, José Antonio Meade went to fulfill part of the ancient ritual and visited the headquarters of the Confederation of Workers of Mexico (CTM), an organization that in other times was in charge of blessing the anointed.

And there, in front of the first non-priista candidate of the PRI for the Presidency, the general secretary, Carlos Aceves del Olmo, summed up, from the wheelchair that he uses frequently since then, the decline of the once powerful labor sector: Before it was called opener, now we are just turning the lid

.

That day in November 2017, the cetemistas and the candidate sweated profusely in a small room, a few steps from the lobby where the statue of Joaquín Gamboa Pascoe, the leader who had 15 million dollars in a tax haven, spends time in the years in which the candidate was Secretary of the Treasury.

Meade came third in the 2018 election and (almost) retired from public life. The man in the wheelchair is still there and on June 15 he came to the rescue of the PRI’s national president, Alejandro Moreno, who is facing double fire from the federal government and his friends from the opposition alliance.

The name of the cetemist leader was the first in a display with a strong smell of mothballs: It is not the first time that the government has tried to destabilize the PRI, even in the past they used mercenaries who have already been expelled from our ranks

.

The tone of the statement contrasts with the treatment that the CTM has given to President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, not very distant from the treatment it gave to the leaders of National Action (It is not a boast, but the CTM was the first to fully recognize the victory of President Felipe Calderón

Gamboa Pascoe said in 2006).

an oscillating relationship

At least in the early days of this six-year term, the cetemist leaders preferred to navigate the waters of the 4T with expressions of disagreement directed at the Ministry of Labor, headed by Luisa María Alcalde, to avoid a direct confrontation with the presidential power.

Aceves del Olmo complained over and over again about neglect of the authority and, above all, of the competition. In the Senate (2019), he accused Pedro Haces Barba, leader of the Autonomous Confederation of Workers and Employees of Mexico (Catem), of showing off his closeness to the President and having the task of ending the CTM.

Time after time, and year after year, López Obrador has repeated what he said at the first Labor Day ceremony he led as President: that his government will not have favorite leaders nor will there be tutelage from the unions.

You can use my name, but let it be known that I represent all Mexicans. It is not true that I have a favorite union

as he said in March 2019.

Thus, the relationship has oscillated between disagreement and mutual applause.

On March 5, 2021, the President led a Mayan Train supervision event and did not stop his speech despite the fact that the horns of the huge dump trucks did not stop sounding. It was the protest of transportation organizations related to the PRI that displayed two demands on their banners: direct contracting of their services and Out Catem!

.

According to the leaders of the CTM and other organizations, the Catem, related to the 4T, has kept half of the contracts in some of the current government’s mega-projects.

The treatment, on other occasions, has been more than smooth. When the commemoration of the 86th anniversary of the CTM took place last February, another story could already be told. President López Obrador sent a congratulatory message: We have achieved many things with Don Carlos Aceves and with leaders of the CTM, for example, we managed to increase the quota for employers and thus increase pensions

.

The CTM thanked the gesture with large letters in its magazine leaders: The President recognizes the historical contribution of the CTM

.

Amparos against union democracy

The arrival of López Obrador to the Presidency set off the alerts in the old Mexican trade unionism. Some leaders believed that the time had come to retire, given that in addition to the change of winds in presidential power, a new model of labor justice came into force aimed at guaranteeing freedom of association and transparency in the always opaque world of collective bargaining.

With the exception of the early retirements of Juan Díaz de la Torre and Carlos Romero Deschamps, the scene moved very little. Both leaders (teachers and oil workers) left all their own in the union structures and the rest of the leaders remained in their positions, at the head of which, in many cases, they have accumulated decades.

In December 2018, as a preamble, the CTM and the Revolutionary Confederation of Workers and Peasants (CROC) were expelled from the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC).

These corporate organizations

the resolution read, continue to carry out actions contrary to the principles and values of the workers and consequently of the ITUC

. Both organizations were accused, at the meeting held in Copenhagen, Denmark, of promoting employer protection contracts, as well as of attacking union freedom and democracy.

The resolution of one of the most important international groups did not worry the leadership of trade unionism in the least charro.

The following year, after the approval of the labor reform, unions of the CTM promoted around 500 amparo lawsuits against different topics of the new legislation. The cetemistas challenged three dozen articles, especially those related to the personal, free, direct and secret vote in the renewal of union directives.

The word that most worried the cetemist leadership was straight

because they had already devised a way to turn around the democratic election of leaders by the indirect route, and always more manipulable, of assemblies of delegates.

In March 2021, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation issued 12 jurisprudence that put an end to the cetemist attempt to derail the labor reform with the argument that it threatened union autonomy.

Formally, the CTM opposed the ratification of Convention 98 of the International Labor Organization, regarding the right to unionize and collective bargaining. Mexican corporate unionism had managed to avoid that step since 1949.

The cetemistas did not vote against it, but Aceves del Olmo himself, on the Senate platform, said that without adapting the laws could create uncertainty in investments, increasing conflicts and putting job creation at risk

.

In a recent trinational meeting that brought together labor lawyers and experts from Mexico, the United States and Canada, researcher Graciela Bensusán stated that Mexican union leaders, both traditional and independent, have three positions regarding the new labor legislation: 1) those who they play the simple simulation, who dream that they can continue the same

2) those who they realize that they have to adapt and now try to have a relationship with the workers

and 3) “the few who think about transformation… who realize that it is not only a change of norms, but of leadership, strategies, alliances.”

The labor reform, for which the political will of the current government was key, said Bensusán, was necessary, but not sufficient for the transformation

because we are facing a hundred years of practices, inertias, cultures

.

With the CTM claiming to be the owner of workers’ representation even in these times, it can well be said with the dean of scholars of the world of work: This reform is not a passport to paradise, it is a path full of obstacles

.