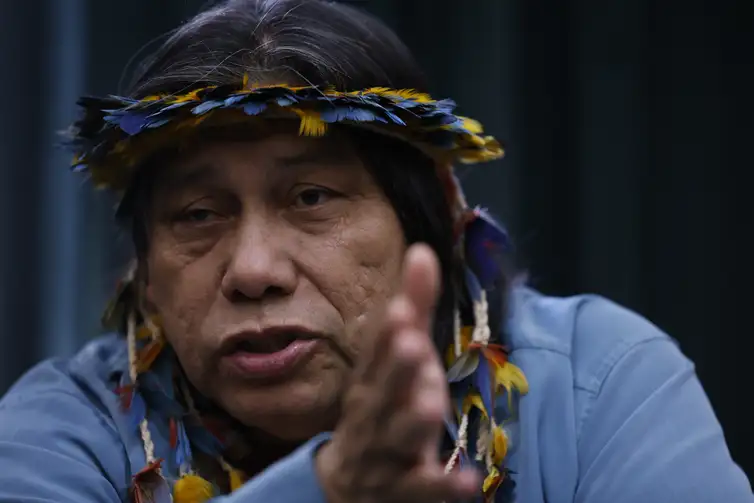

Nature comes food, housing and spirituality. Also inspiration for poems, short stories, chronicles and philosophical reflections. Indigenous writers such as Daniel Munduruku and Márcia Wayna Kambeba build a literature engaged with the forest and the values of traditional peoples.

Therefore, in addition to authorities in the art of writing, they specialize in assessing how different types of pollution have impacted ecosystems and populations living in direct tune with nature.

And when it comes to perspectives for the future, the tone is of concern and some pessimism. They understand that an effective climate policy, capable of containing global warming and deforestation, would necessarily depend on a radical transformation in consumer and production structures on the planet.

The report of Brazil agency He interviewed Munduruku and Kambeba at the headquarters of the Banco do Brasil Cultural Center (CCBB) in Rio de Janeiro. The conversation took place a few hours before their participation in the Reading Club, where they talked about the books Of the things I learned: rehearsals about the welcome (2014) and Forest Knowledge (2020).

In common, the works speak of learning and knowledge acquired from the experience with nature. Of a worldview that values integration and the collective good. Elements that writer Daniel Munduruku understands not being part of the western world. This absence is a fundamental part of the climate crisis. And the existential crisis.

“We start from two completely opposite perspectives. There is no way the western capitalist world becomes a collectivity. There are many centuries by building a society of the individual. And we value the collective, which does not speak only of humans. No being of nature lives alone,” says Munduruku.

“Western vision is based on linear time and a future on which individuals are all the time speculating. They bet on a time when they will come, where they think of living happiness. Everything is illusion. And then, one creates a paradise where they will one day come. So we are all forgiven by our sins. Amen. You can only live this one now, ”he adds.

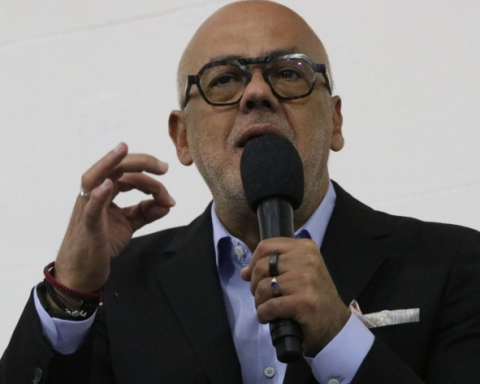

Environmental issues have received increasing attention with the proximity of the 30th United Nations Conference on Climate Change (COP30), scheduled for November, in Belém. Márcia Kambeba understands that a successful event would depend on more radical agreements.

“What do we really want with COP when we think of the climate issue? It depends on the environmental issue, the preservation and conservation of nature. On the resumption of consciousness in relation to waste and the environmental impacts we produce. People do not want to talk about it. There is no real awareness that the mode of consumption generates so many impacts,” says Kambeba.

Munduruku shares of pessimism about the gains that COP30 can bring to the environment and the people who live directly in harmony with it.

“We have come to an impasse that if we are not nature again, the tendency is not to survive. And COP30 is not a meeting to save nature. It is a meeting to save the economy of the world. That is, it is an absolutely impossible contradiction to resolve, because the economic hegemonic system will not stop,” says the writer.

“It’s no use calling [escritor indígena] David Kopenawa to make a speech. Because his speech impacts nothing on the issue of banks and money. What the indigenous defends is the maintenance of life on the planet. And what the bankers argue is to maintain their wealth, ”he adds.

Literature and Resistance

Even if projections are not so optimistic, the Indigenous writers will hope that some changes begin through literature. In the ability she has to sensitize, inspire and transform.

“Literature is a way of recording memories, narratives, oralities, truths that our ancients taught us. The memory pulsates all over our body. The voice of the river, the forest voice, the voice of birds, the enchantment to protect the established relationship between man and nature,” says Kambeba.

“And that we will turn it into the Welcome. We want to bring this writing and these teachings shared for both those who live in the village and those who live in the city,” he adds.

Munduruku argues that indigenous people have a long repertoire of resistance and this is reflected in books, in order to impact more and more people.

“It was an achievement for the indigenous movement itself to have more space for indigenous writers since the late 1980s. Our voice gains more space and autonomy. And we reinvent our insertion in society. If today we have more than 100 indigenous authors producing it is because each one is making their way, but clinging in hand in hand. And we are educating new generations to think in a more inclusive, more human way.