Faced with the climate emergency, the debate on ways to promote sustainable development in the Amazon is gaining momentum in different economic sectors, including tourism. In indigenous lands, a management model has proven to be an alternative for people who want to receive visitors and, at the same time, keep the forest standing: community-based tourism.

In the municipality of Feijó, in Acre, the people of Aldeia Shanenawa have the experience of receiving visitors interested in immersing themselves with the original people and learning about harmonious coexistence with the forest. “In the past, we had already had our own festival, when our relatives came from other regions, other ethnic groups came, and we had our cultural festival, but we still didn’t have this experience with tourism. Tourism really arrived in the village three years ago”, recalls chief Tekavainy Shanenawa.

According to the indigenous leader, in addition to the festival, Brazilian and foreign visitors began to arrive at the Katukina Kaxinawa Indigenous Land (TI) in search of ancestral knowledge of forest medicine, with the use of ayahuasca, which remained stored for 30 years during a period in which that the practice was prohibited. “The ancients kept the wisdom of medicine all this time. We were able to consecrate again when I was an adult and had children, practicing what my grandfather taught me”, he says.

Before the arrival of tourism, the Shanenawa had subsistence agriculture as their economic base, cultivating mainly bananas and cassava, hunting and fishing and the production of handicrafts. Before the arrival of tourism, the Shanenawa had subsistence agriculture as their economic base , cultivating mainly bananas and cassava, hunting and fishing and the production of handicrafts, including beans, corn and cassava”.

According to the chief, the trade in these products began to finance the purchase of animal protein and other necessary goods purchased in the city. The arrival of tourism was well-accepted by members of the village, who realized the possibility of adding value to production and also strengthening culture and teachings for future generations.

“When we consecrate medicine, it strengthens us more and more, especially the youth, who are learning. When visitors come, we have the pleasure of showing them how they live and how medicine is dedicated. And, each time we consecrate, we improve more”, says Maya Shanenawa, the chief’s eldest daughter.

Tradition

Among the Shanenawa people, whoever is born first continues the chiefdom, regardless of whether it is a male or female child. The vocation also prevails. In addition to Maya, who at 29 years old is already recognized as vice chief, the second daughter, Maspã Shanenawa, had her vocation recognized by the community and already leads the medicine consecration ritual.

For the Shanenawa, this entire tradition is strengthened by tourism: young people choose to stay in the forest and continue their culture, and the indigenous people lead their own narratives.

“I say that people always saw the book, which told a badly told story. And today I have this opportunity for every person who comes to experience tourism here in my village, has the opportunity to take this story told by us, the story that I heard from my grandfather”, says chief Teka.

Partnerships

Active participation by the village and fair sharing of benefits are basic principles for community-based tourism to happen in indigenous lands, but it does not always happen this way. One diagnosis drawn up by the Ministry of Development, Industry, Commerce and Services showed that, in many cases, the partnership offered to indigenous peoples disadvantages the community.

The Shanenawa People are aware of this issue and seek partnerships that strengthen tourism in the IT. One of the companies that works directly with indigenous people chose representatives from the community itself.

Tuwe Shanenawa, one of those who works directly with travelers, says he feels proud to show the forest and guide those arriving from abroad through ancestral knowledge. “I always say that no one gets here by chance and, in particular, I mention travelers. In some way, it is a calling on your life. Or medicine, or just for everyday life. But no one gets here by chance, no. Of course it comes with the objective of tourism, of getting to know people, but it goes much further than what people are sometimes expecting, because of the spiritual connection.”

In addition to Tuwe, everyone who works with tourism in the village strives to improve the experience of those who arrive, be it the natural food harvested and cared for in the forest, or the tour to discover the beauty of the Amazon and the majestic samaúma, a tree that it can reach up to 70 meters in height and last 120 years, or in the herb and clay baths that prepare the spirit for the consecration of medicine.

Challenges

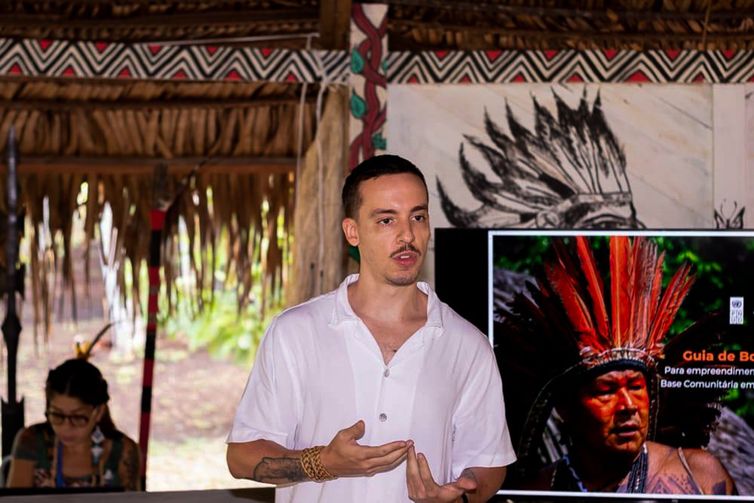

In the opinion of Pedro Gayotto, co-founder of the social tourism company that develops activities with the Shanenawa people, there is still a repressed demand from tourists who seek ethnotourism, but do not know how to get there.

“The vast majority of travelers who take trips to indigenous lands with us always arrive with: ‘I was looking for a long time to go on an indigenous trip and I didn’t know how, I didn’t know where to start, and I found you on someone’s recommendation. , I found you on Google’, anyway. So, this already demonstrates that there is demand and [que] people don’t know how to get there”, highlights Pedro Gayotto.

In addition to the challenge of getting travelers to their destinations, there are many other obstacles to overcome. The realities of each indigenous land are different, however, there are collective issues that affect most villages. An example is the waste generated by tourist activity. “We understand that burning garbage is not the best way and we also don’t want to take it somewhere else. So, we need help to find a solution”, warns Tuwe.

Task Force

The issue was one of the challenges presented during the launch of the diagnosis commissioned by the Ministry of Development, Industry, Commerce and Services and developed by the Samauma Institute, which took place in Aldeia Shanenawa under the eyes of representatives from the ministries of Culture and Tourism, the Institute of National Historical and Artistic Heritage (Iphan) and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP).

During the almost five-day task force, between December 2nd and 6th, the Shanenawa were able to present their demands and forward processes to regularize community-based tourism activities with institutions.

Guided by Normative Instruction 3/2015, from the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples, tourism in ITs is still poorly documented by federal agencies. Only 39 routes are regularized throughout the national territory and, of this total, 14 focus on sport fishing.

According to the general condemner of Sustainable and Responsible Tourism at the Ministry of Tourism, Carolina Fávero, this information deficiency has already been identified by the body, which is currently working on mapping these initiatives. With work still in progress, 150 villages with tourist activities have already registered, highlights Carolina.

“We created a project in partnership with the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, which is Brasil Turismo Responsável, focused on indigenous communities. And then he will work precisely on training in responsible tourism, in community-based tourism, supporting communities in the development of the Visitation Plan and, in addition, taking courses, training, producing materials and mapping, which is already underway”, he concludes. .

*The reporter traveled at the invitation of the Samaúma Institute and the Ministry of Development, Industry, Commerce and Services