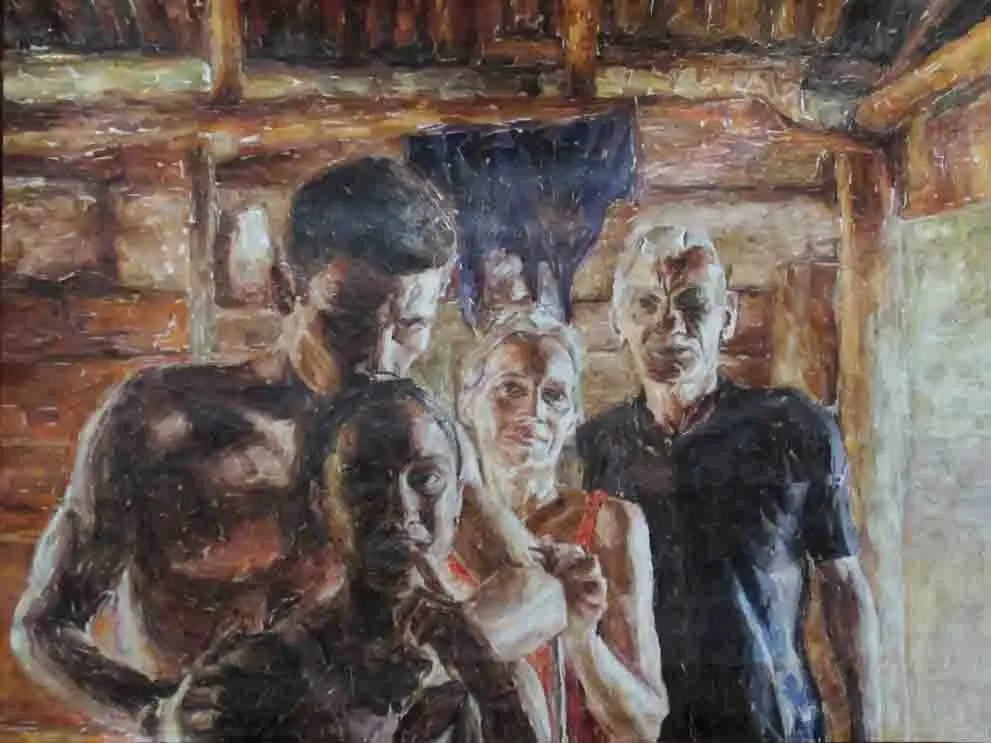

Daymara Orasma puts the finishing touches on her next personal exhibition, 15 collages of various formats and on three supports – fabric, paper and wood – with which she continues to explore the theme that has made her known in the panorama of the visual arts of our country: the Cuban countryside, its rugged solitude, the visceral and dignified elementality of the workers of the land.

It is not about customs, nor about works of bucolic exaltation. The course he has chosen is that of the anthropological record of his own family at this very moment, the 21st century of virtuality and artificial intelligence, a crazy century of rearrangement of the vectors of force of international politics. Theirs is a kind of social realism that draws from diverse sources, from Honoré Daumier to Gustave Courbet, passing through Jean François Millet, an artist for whom he feels a real devotion.

While the great powers compete for the world’s natural wealth and areas of strategic value, these men and women from a small hamlet of Mane Güira They bow every day before the earth, listen to it, caress it, plant it to obtain essential foods, oblivious to everything other than the forecasts that the cabañuelas paint every year.

It is a parallel world that exists a few kilometers from Havana, time capsules where life seems stagnant, almost without any of the benefits of modernity.

The artist comes from there, and she assumes it—she assumes—with the naturalness of someone who exhibits a way of life, a material culture and customs that have shaped her as a being. Its purpose is not social denunciation, although there would be much to denounce in an environment so precarious that it would seem left to the hand of God? She records, through her empathetic gaze, the day-to-day life of a human group that insists on existing against any design, beyond slogans and denying narratives.

When I ask him about his artist’s cuisine, about the creative process that takes shape in the work, he answers:

“The process begins with trips to the countryside where my family lives. I spend a few days there, and I take photographs of the daily life of the rural residents. At dawn, I go with my father to the farm where he works. See the dawn, the farmers preparing for a very hard work day that becomes critical after ten in the morning, when the sun dehydrates even the stones. I go as a reporter, but I end up helping my father and my brother; it is inevitable when I see them work. I experience the work that they do. I finish my visit and return to El Vedado, where I currently live. On the trip, I feel like I am leaving behind a simple life, a humble life that belongs to me, but I must continue exploring other horizons and begin to prepare the images that move me. “The right color. When I say the color, I also mean the brushstroke, because for me gluing a piece of paper is like applying a brushstroke. I have to search a million times in magazines to find all the colors, shades, the right range for each job. The process and the result are the same as painting with pigment and a brush;

Come in and forgive yourselfis the title of a collection of poems by Indio Naborí that Daymara borrows. In turn, the decimist had picked up the phrase from the peasant speaker, a way of providing hospitality to the visitor, as well as an excuse for the poverty of his surroundings.

I find a great conceptual density in Daymara’s operation. Her virtuoso works are made up of magazine rips that exalt glamor and banality, exactly a field of references diametrically opposed to what she intends to reference. This obvious irony is reinforced by the title of some pieces such as “The Taste of Hunger” and “Country Lunch.” The latter, far from alluding to a recreational excursion, presents us with two messy beings who eat their food at the workplace.

Come in and forgive yourself, Daymara tells us, generously, so that we can take a look at her world. At the beginning of March, the artist will be waiting for us with open arms. We might even get a little cup of coffee.

That: Come in and forgive yourself, exhibition of collages by Daymara Orasma.

Where: Oswaldo Guayasamín House Museum. Obrapía 111, e/ Oficios y Mercaderes, Old Havana.

When: From March 6 to April 6. Tuesday to Friday, between 9:30 am and 3:00 pm. Saturdays, from 9:30 am to 1:00 pm.

How much: Free entry.