Delfin Prats Pupo He turned 80 on December 14 and, although he is not a man of stridency, that anniversary should not pass him by. They told me that he celebrated it in his little house in the dusty neighborhood of Pueblo Nuevo, in Holguín, where he has lived for more than two decades. Friends, poets, faithful affections arrived there who have sustained his work and, above all, his life in the harshest stretches: those of silence, scarcity and adversity. There was no solemnity or protocol. It was, like almost everything in Delfín, an intimate encounter, woven with conversations, ancient loyalties and that form of memory that is not imposed, but accompanies.

I met him in January 2006. I went to his house with the poet and journalist Leandro Estupiñán Zaldívarwho was going to interview him. I was just starting out in photography and knew little about the man Leo spoke of with almost reverential admiration. I remember the door, the neighborhood, the light; and I also remember the immediate feeling of being in front of someone who needed no introduction.

Delfin did not pose: he offered himself. It allowed the camera to enter a zone of trust where the poet, in reality, takes a self-portrait and the photographer barely accompanies him. We came out transformed from that meeting. Leo published a memorable interview weeks later in The Gazette of Cuba. I was left with a series of portraits that I still consider unrepeatable today and with a certainty that grew over the years: each return to Holguín had to include, for simple emotional coherence, a visit to Delfín.

On this birthday, rather than insisting on the literary dimension—indisputable inside and outside the island—I want to emphasize its human stature. Delfín belongs to a rare breed: that of those who live as they write, without duplicity. He has immediate gestures, frank hugs, a hospitality that defies precariousness. In a country where sometimes scarcity also narrows the spirit, he opens the door, the time and the conversation with a generosity that does not seem calculated.

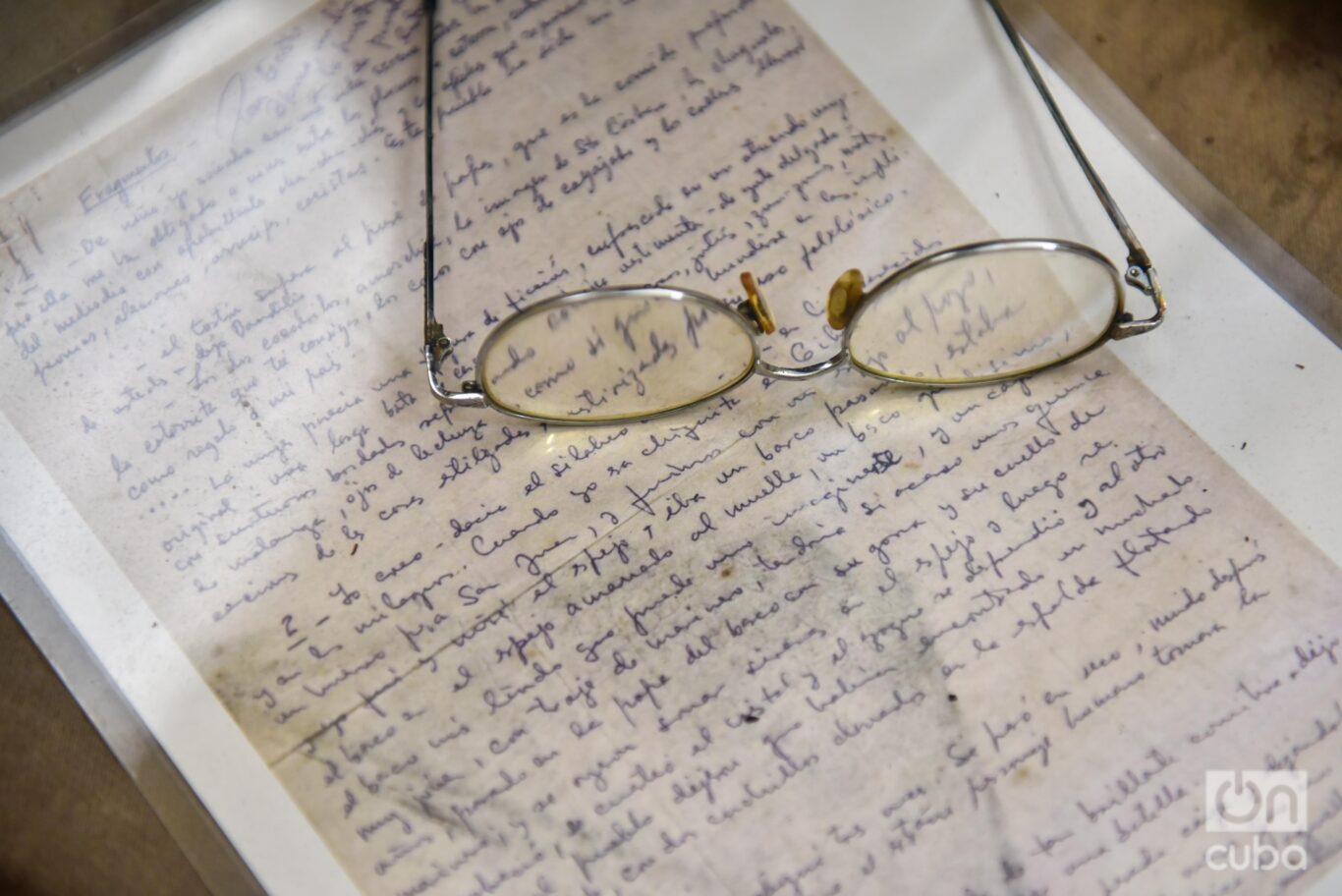

At our last meeting, a couple of years ago, he insisted on giving me the only photo of him as a young literacy teacher. On another occasion he gave me his only copy of Open the constellationsa book that came out riddled with typos and that he corrected for me, verse by verse, with blue ink, as if each rectification were a form of care. This generosity is not a decorative gesture: it is an ethic. And that ethic, at Delfín, has been a silent — but firm — way of resisting.

His biography also tells a bigger story. Born in 1945 in La Cuaba, on the outskirts of Holguín, he studied Philology and Russian Language at the Lomonosov University in Moscow and worked for years as a translator. In 1968 he won the UNEAC David Prize with language of the mutea precocious and dazzling book that was censored and destroyed shortly after. That act of symbolic violence pushed him into a long editorial silence in Cuba.

He did not publish again on the island until 1987, when To celebrate the rise of IcarusNational Critics Award. Since then, his work has established itself as one of the most unique in contemporary Cuban poetry: brief in quantity, inexhaustible in density.

Perhaps that is why – because he never negotiated with stridency or with the most accommodating circuits – it took so long to give him the National Prize for Literature, the most important of Cuban literature, which he finally received in 2022. It is not a settling of scores, but rather evidence: Delfín has remained outside the most visible legitimation machines, faithful to an idea of poetry as a rigorous craft, not as a showcase.

To get a little closer to your native universe, on the occasion of your birthday, I return to language of the mutethat “cursed” and foundational book, and I share the poem “Favorite Site.”

There childhood is neither a postcard nor a refuge: it is a harsh, sensory, sometimes disturbing territory, where desire, play, violence and death coexist. Memory appears as a sediment that returns in fragments and not as an ordered story. That is why his verses do not seek to explain or console, but rather to expose. And, when exposing, they make people uncomfortable with beauty. In that discomfort lies a good part of its validity: Delfín is not a figure frozen in homage, but a living poet, with a work that continues to dialogue with the most complex of human experience and with a life that sustains, without noise, the weight of his words.

favorite place

On this site we have been growing

under the protection of the beasts

we made love between their females

We suck the milk of the snails from their udders

and the rituals

in the white segments river

They are stuck in the ground: children’s bodies

and insolently naked laughter

my brother making fun of black girls

asking them for the bun

those years troubled like the pond

of the pigs

“I have made my rifle

with a stalk that I plucked from the coconut bush

a bracelet with a red rag

from mom who was behind the closet

Tomorrow I’m leaving with the rebels.”

the women laugh and spin

wrapped in a drowsiness of camphors

and concentric circles of milk

I have sat on my brother’s head

the women wear their green suits

And you like my aunt’s blonde thighs

They leave in a red wagon that creaks

and they already cross the bridge that you make

of the arch of your body over the river

when I say goodbye they are smoke

They distribute chocolate and saltine crackers

the dead visit me this afternoon