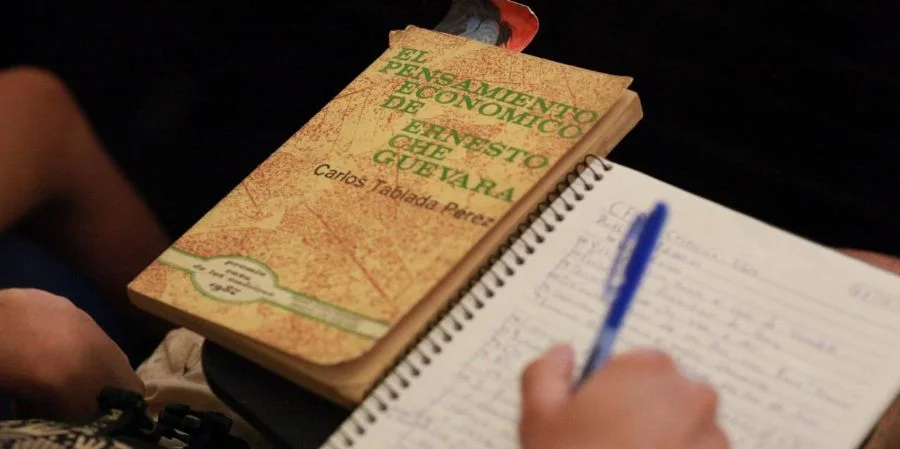

HAVANA, Cuba. – This October 8, coinciding with the 57th anniversary of the physical disappearance of the Cuban-Argentine guerrilla Ernesto Che Guevara, was presented in it Fidel Castro Ruz Center a new edition of the book The economic thought of Che Guevaraauthored by the Cuban academic Carlos Tablada. It is a text that already has more than 40 editions, and that has represented for almost four decades a kind of catechism for the most radical left internationally.

Anyone would think, especially taking into account the author’s total identification with the Cuban regime, that the book would always have had an obstacle-free path to publication. And, in truth, it didn’t happen that way.

Tablada began writing the book in 1969 and concluded it in 1984. But in this last year the Island was still going through the period of Sovietization that had begun in 1975 with the celebration of the First Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba, and for this reason the Che, who had strongly criticized the system of Economic Calculation prevailing in the Soviet Union ―and also copied by the Cubans―, was kept in oblivion by the Castroist machinery of power.

Everything would begin to change in 1986, following the implementation of the policy of eliminating errors and negative trends, announced by Fidel Castro, partly fearful of the winds of Perestroika that were already blowing from Moscow. Carlos Tablada’s book won the Casa de las Américas Prize in 1987, and was finally published in Cuba.

The maximum leader’s speech in 1987 was significant, commemorating the 20th anniversary of Che’s death. On that occasion the ruler called to “study” Che. It is said that Castro forced all government officials, as well as the general staff of the Armed Forces and the Ministry of the Interior, to read the aforementioned book.

The turn that the Cuban economy took in that year 1986 consisted, fundamentally, in abandoning the timid market levers contained in the economic calculation system to return to a centralism that aspired not to neglect the work on the consciousness of the “new man” that was desired to form.

In that context, of course, Che’s economic ideas fit perfectly, which advocated suppressing monetary-mercantile relations between companies, restricting the action of the law of value in socialism, giving priority to moral stimuli to the detriment of material stimulations, and make people work out of conscience, and forget about concepts such as interest, profit and profitability, among others.

Of course, such ideas do not retain even a bit of validity today. Economic centralization, forgetting market mechanisms, has failed everywhere. The examples of China and Vietnam are an eloquent example of this. Despite maintaining a totalitarian political system, these countries implemented pro-market economic reforms to move their economies forward. Even in the Cuban case, the rulers have had to resort to market levers every time the Island’s economy hits rock bottom, as happened in the 90s.

However, Carlos Tablada’s book, which thoroughly explains all those idealistic conceptions of the ill-fated guerrilla, is useful, from time to time, to certain rulers. That is the case of what is happening these days in Cuba, when we are witnessing an anti-market offensive that seeks to suffocate non-state economic actors.

We do not doubt that Tablada’s text will soon be incorporated into the study plans of the national education system, as well as into the political circles of the country’s mass organizations, appendages of the Communist Party.