HAVANA, Cuba. – During its very long regime of 66 years, Castroism has amply demonstrated that it does not agree with poets who do not serve its interests and sing its praises.

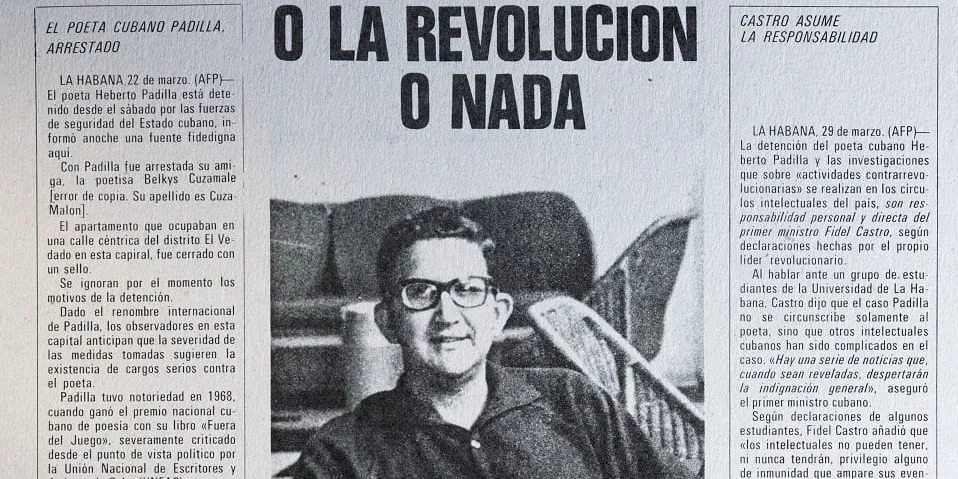

The list of poets who have spent these six decades in prison for opposing the regime is long: Ángel Cuadra, Ernesto Díaz, Jorge Vall, José Mario, Heberto Padilla, Belkis Cuza Malé, Tania Díaz Castro, María Elena Cruz Varela, Raúl Rivero, Manuel Vázquez Portal, Jorge Olivera, Ricardo González Alfonso, etc.

Many others have been forced into exile, such as Gastón Baquero, Isel Rivero, Ana María Simo, Lilian Moro, Manuel Díaz Martínez, Ramón Fernández Larrea, Joaquín Gálvez, Legna Rodríguez Iglesias and a long etcetera.

And countless poets have opted for isolation, from Dulce María Loynaz, who, not hiding her rejection of the communist regime, locked herself in her mansion for decades, to Rogelio Fabio Hurtado and Rafael Alcides, who refused to publish their books so as not to allow themselves to be manipulated. by the cultural commissioners of Castroism.

But existence has not been easy for those who have offered to serve the regime if they have not done so unconditionally, full time and without giving rise to doubts, such as Roberto Fernández Retamar, El Indio Naborí, Manuel Navarro Luna and Félix Pita Rodríguez .

Nicolas Guillen He was promoted to the rank of “National Poet” and named president of UNEAC, which made him, to the detriment of his work, the chief bureaucrat of official culture. But he had to swallow bitter words, like when in 1971 he had to feign illness so as not to attend the meeting to witness Heberto Padilla’s self-incrimination; or when he endured the disrespectful public scolding of Fidel Castro, who called him “lazy” because “at UNEAC he only dedicated himself to feeding the pigeons.”

The regime took advantage of the idyllic anti-liberal nationalism and the teleological vision of Cuban history of the poets of the Orígenes Group, fascinated in their beginnings by Fidel Castro’s Revolution. But he soon became upset that they were bourgeois and Catholic and used different standards to measure and use them.

Lezama Lima was initially criticized for what they considered “the elitist hermeticism of his poetry.” Then they censored him paradisethe crowning novel of Cuban literature, because the homophobic morality of the commissioners disliked chapter VIII. For having been part of the jury in 1968 that, despite all the pressure, awarded the poetry prize to Out of the gameof Heberto Padillathey ostracized him until his death in 1976. But, as they did with Virgilio Piñera, who was ostracized for his homosexuality until the end of his life, Lezama was posthumously rehabilitated by official culture by turning him into a cult writer. only for beginners. They want to show that he was never an enemy of Castroism, citing Lezama’s ambiguous invocation of the Angel of La Jiribilla and that much used and abused phrase of the writer when in 1959 he stated that “the Cuban Revolution means that all negative spells have been decapitated.”

The official recognition of Cintio Vitier (and also his wife Fina García Marruz) took decades, until the 1990s, when Castroism, by adding Martí’s nationalism to Marxism-Leninism, incorporated him into the ranks of its organic intellectuals.

Eliseo Diego, who never denied his Catholicism since, unlike other Origenists, he limited himself to an allegorical and less teleological reading of history, had more recognition. Despite the fact that State Security entrusted his son Eliseo Alberto with monitoring him, as he confessed in his book Report against myselfthey never stopped publishing him, not even during the Black Decade. Perhaps that is why, in gratitude for the official recognition, he felt obliged to write in 1980, during the Mariel exodus, the infamous sonnet “A uno que se va”, and that ridiculous and forced pro-Soviet note at the bottom of the prologue of Chimera Newsfrom 1975, where he compared “the sinister American war insects devastating the land in Vietnam” with “the peaceful cranes and naive tractors that we see in Cuba and I saw recently in Uzbekistan, working, not for the benefit of a single Moloch belly, but for the good of all.”

Lina de Feria, Delfín Prats, Nancy Morejón and César López, once marginalized, were rehabilitated and awarded the National Prize for Literature.

Nancy Morejón, who was one of the dozens of authors retaliated after the closure of Ediciones El Puente, in the mid-1960s, by orders of Fidel Castro, confessed on one occasion, many years later, that she felt afraid every time she Their presence was spoken of as “the people of El Puente.”

It is assumed that the same thing happens, although he does not admit it, to Miguel Barnet, who also started in El Puente.

In 1988, Carilda Oliver Labra was beaten when a group of paramilitaries attacked poets who were participating in a literary gathering chaired by her at the El Ateneo bookstore in Matanzas.

And there is the pathetic case of Raúl Hernández Novás who, in 1993, kicked one of his best friends, also a poet, out of his house, out of temperate boxes, and never spoke to him again because he dared to make a comment in his presence. contrary to the regime. A few months later, Hernández Novás committed suicide. He made that desperate decision because he and his elderly father were literally dying of hunger, after a state soup kitchen stopped giving them the measly ranch they gave him daily. He had fallen into disgrace and UNEAC did not respond to his requests for help.