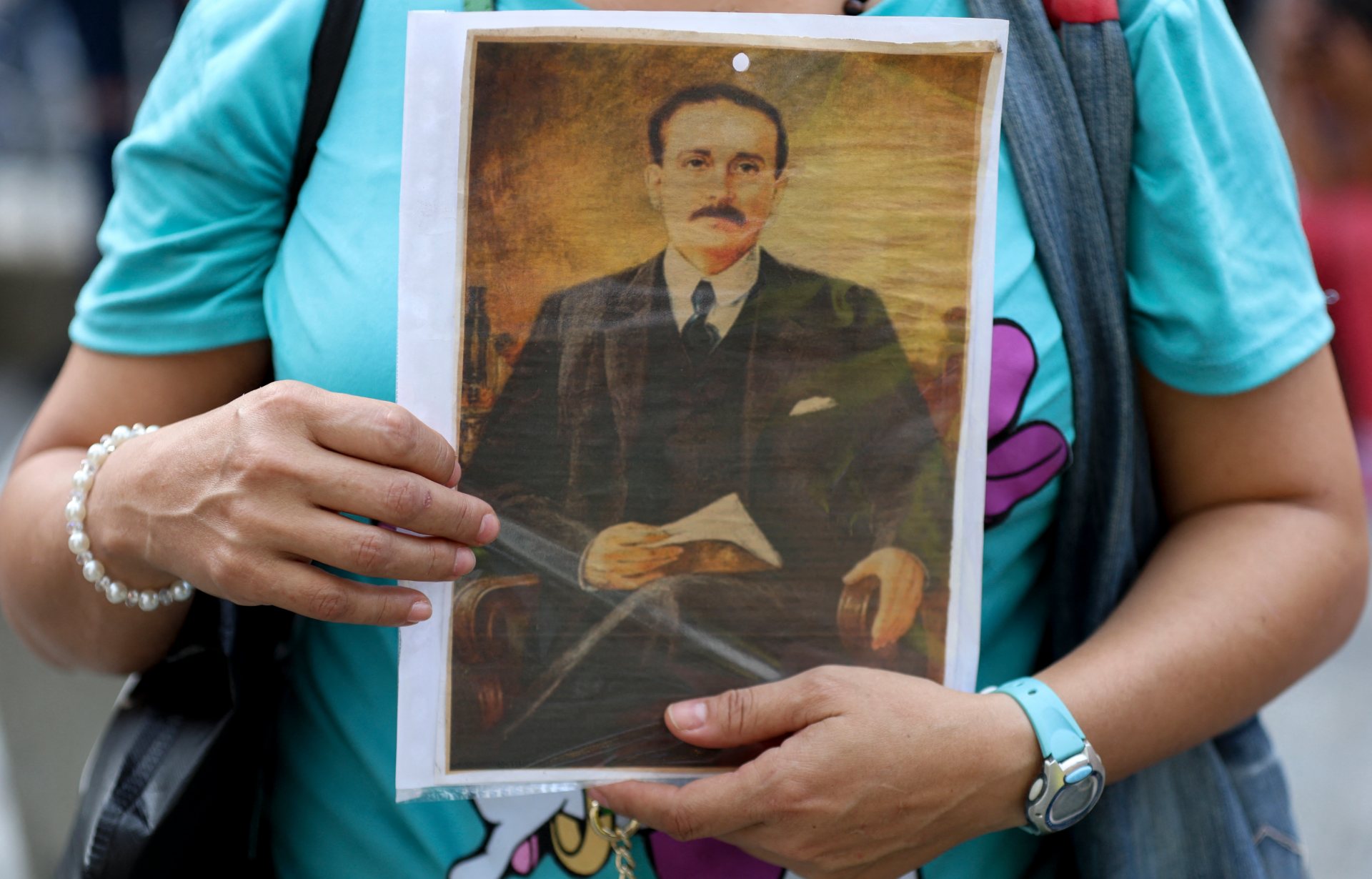

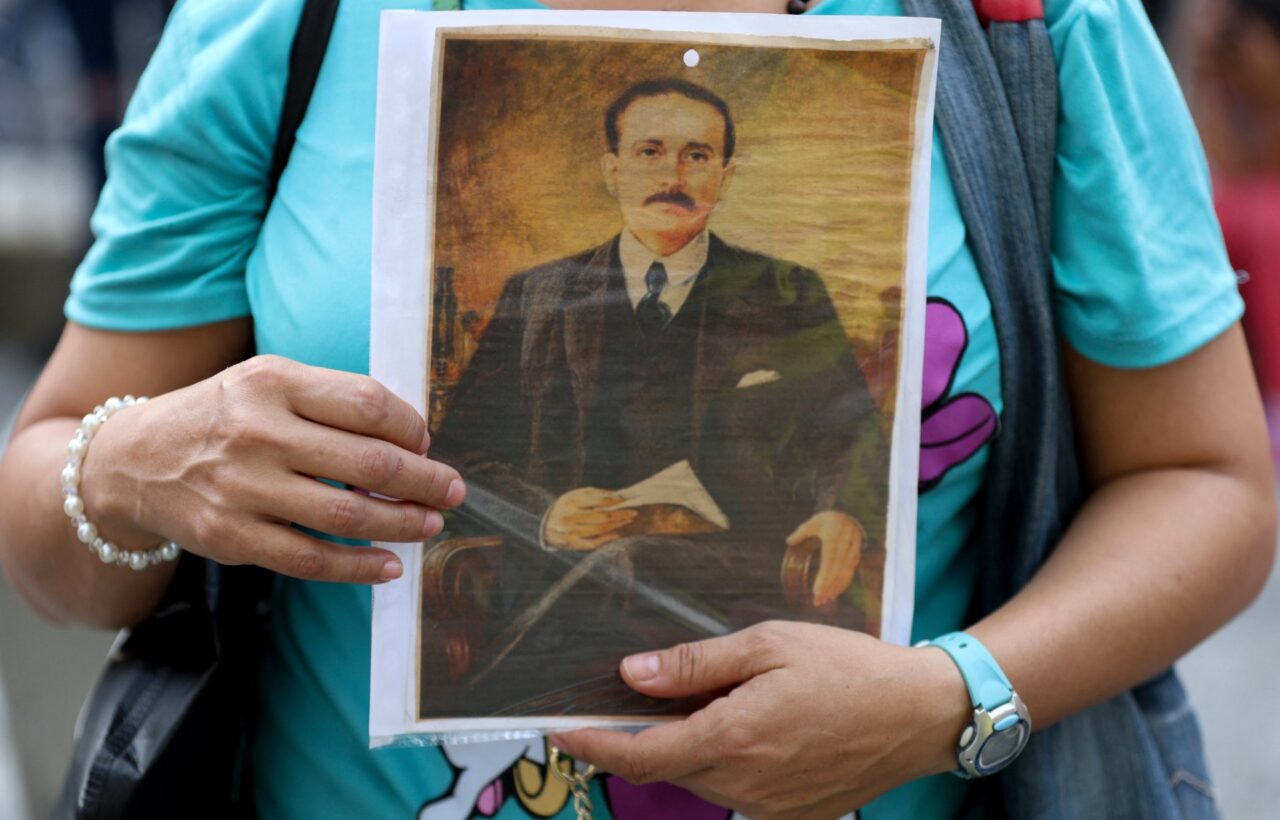

On Sunday, October 19, Pope Leo XIV will canonize the Venezuelan doctor Jose Gregorio Hernandez in St. Peter’s Square, Rome. At last. More than a century had to pass since his death, which occurred in Caracas on June 29, 1919, and seventy years since people began to talk that a saint had been born among us and that He had become a doctor at the Central University of Venezuela.

Many people have worked so that on that day that serious man, wearing a black hat, whose photo we Venezuelans of any conviction keep in our purses and deposit at the bedside of our loved ones, ascends to the altars. But in the last decade, none of the parties in this struggle has contributed as much to its victorious crystallization as Cardinal Baltazar Porras.

—What does a canonization mean, what is its value in the 21st century?

—The fundamental meaning is that this recognition made by the Pope, the Holy See, turns the canonized person into a model and universal reference. That is the only difference between beatification and canonization. With the beatification he is worshiped in the area where he lived, where he carried out his activity, but he does not yet have the level of recognition to be included in the universal calendar. Starting on October 19, the day of the canonization, the feast of Jose Gregorio Hernandez (JGH) will be on October 26 in the universal calendar of the Church. That day the memory of José Gregorio Hernández will be celebrated in the world.

—Will October 26 be the day of San José Gregorio Hernández?

—Yes, because the Holy See designates a date, which is normally the date of death, but he died on June 29, which is the feast of Saints Peter and Saint Paul and, well, that feast covers everything. Then, at our request, the date of his birth was chosen: October 26, which in the liturgical calendar of the universal Church will be the day of the feast of Saint Joseph Gregory.

—What does the man from Trujillo contribute to a neighborhood where none other than Pedro and Pablo are already present?

-A lot. For the specific person of José Gregorio, for the transcendence of his messages. Not only what we know, that he was the doctor of the poor, but that his message is from a baptized person, from a layman. He was not a priest, he was not a nun, he did not hold any position in the Church; and yet, his significance is much greater because he was a worshiper of peace and coexistence between different people. Proof of this is that he had no problem working with Luis Razetti and other doctors who could believe [en Dios] or not, but what united them was the health of Venezuelans, the good of Venezuelans, which is above anything. For this reason, after his death, the first testimonies were from non-practitioners such as Dr. Razetti, who was agnostic, or Rómulo Gallegos. They knew that there was something different in that man, difficult to understand, something admirable.

And there is that vow, that of offering his life if the First World War ended. [1914- 1918]something that was known later. Well, it turns out that the Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918 and José Gregorio died a few months later, on June 29, 1919. For this reason, Pope Francis appointed him co-patron of the Chair of Peace of the Lateran University, which is the pope’s university, where on Friday the 17th there will be an academic event chaired by the rector, but the main speaker will be a Venezuelan, Monsignor Edgar Peña Parra, substitute in the Secretary of State.

—Will you also participate in that event at the Lateran University?

—Yes, and I will insist that José Gregorio Hernández’s message is very topical. He is not a saint of the past. On the contrary, in a divided country, in a country with intolerance, the character who most unites Venezuelans, whether they are believers or not, whether they are on one side or the other, is him.

—Why did this canonization take so long if, as you say, the merits were very clear?

—The explanation is very simple: in Latin America we do not have a tradition of making causes for saints. That of José Gregorio was the first cause of saints to be opened in Venezuela and it was opened thirty years after his death. Many steps have to be followed and, we, who can be a bit folkloric, believed that it was enough to affirm that miracles had occurred. This must be documented, presented according to established codes; In short, comply with a series of very strict rules that were overlooked. But we were lucky enough to arrive in Caracas, where I was able to form a good team and, well, the cause was carried out, fulfilling everything and, of course, crushing things.

—You made, then, a file that was no longer folkloric but professional.

—And Pope Francis, after reading it, told me: “We are here before a great saint, who has great relevance for today’s world.” Pope Francis told me that he had heard of a very miraculous Venezuelan doctor, but that he had no further information.

—In other words, there had also been a failure in communications, in telling José Gregorio’s story.

—It’s possible. Also because the one who made José Gregorio a saint is the people themselves. But that task, that of communications, is also accomplished.

—There is something that draws attention and it is the fact that you rub shoulders with popes and are the one who keeps the evidentiary files of José Gregorio’s sanctity, but your name does not appear in the programming put forward by the Maduro regime regarding the canonization.

-Who? Where. No, I will be next to Leo XIV.

At this point, Cardinal Porras seems to lose the energy shown since the beginning of the conversation. Suddenly, he looks tired, he contorts himself to look for his lost cell phone between the sofa cushions. He locates the device and takes a look at it without interest. It is evident that I have raised a matter that bores you.

“I will be in the Vatican, next to Leo XIV,” he finally answers.

The role of Cardinal Baltazar Porras in the process of canonization of José Gregorio Hernández has been leading and fundamental in the final stage of the cause. Not for nothing has he been identified as the main promoter, the strategic leader of the blessed cause on his route to the altars. To begin with, he did not sit and wait for a miracle to arrive, but rather he looked for it, he obtained it, he documented it and he took the files to the Vatican. His arrival to the Archdiocese of Caracas, in fact, meant a radical change in the dynamics of the process to which he dedicated himself, and his closeness with Pope Francis has been highlighted as a key factor in accelerating the process.

Although the postulator (in Rome) and the vice-postulator (in Venezuela) are the technical managers, Porras, as archbishop of Caracas (the archdiocese where the cause of the miracle occurred) and as cardinal, is the highest-ranking figure who has promoted the cause and representedbefore the Holy See, the fervor and will of the Venezuelan Church and the people. Canonization has been the top priority of his administration, which explains that Hernández’s cause, in process for decades, was expedited and entered its final stage with the intervention of Porras as a catalyst for its successful completion. The whole world knows that and the heavens too.

But, when the time comes for the ceremony for which Porras has fought so hard, the Maduro regime adopts a position of appropriation with clear political implications, issuing official statements and organizing celebrations in Venezuela whose cast does not include Porras, cardinal, archbishop emeritus of Caracas and, without a doubt, the great promoter of the canonization of JGH, but another high-ranking figure of the Church Venezuelan, who has participated in the coordination meetings with the Maduro regime for the celebration of the canonization.

There are others who meet with the commission of the regime identified in various international instances as a systematic violator of human rights. They don’t even mention Porras. But this afternoon in Madrid, on the way to the Vatican, he doesn’t feel like talking about it. He changes the subject, pretends that he has not heard what is being asked, it is as if he is talking about something very remote or very insignificant.

—There are a number of bishops —he says in a delayed response to the question of communications— here, in Spain, but also in countries throughout Latin America, asking me to go and preside over mass for José Gregorio. But I have explained to them that I cannot, because I am going to preside, on October 26 in Isnotú, that is, on his date of birth and in his town, the events that the people of Trujillo are preparing, which are certainly being thrown away by how well they are doing. And now Isnotú becomes a site of not Venezuelan, but universal significance.

—It has been said that the delay in canonizing JGH was influenced by the fact that he had been co-opted by the so-called “rogue courts” or something like that.

—It is worth distinguishing the popular roots of the cult of José Gregorio in contrast to those who make commercial use of his figure. The thousands and thousands of plaques that believers bring to Isnotú attest to the faith of the people, in the intercession of the pious doctor before God to heal them. There are thousands and thousands, there is nowhere to put them. And in La Candelaria there are more than five tons of little miracles, figurines that represent parts of the body that have been healed thanks to the help of the saint of empathy. That’s why José Gregorio should not be advertised or advertised, because his name alone attracts thousands and summons faith and emotion. Since the Council of Trent, in the 16th century, no one can be worshiped within the Church until he or she is declared a saint. With JGH it has happened that, at the moment in which the Church has recognized public sanctity and that it can be worshiped, the business of those who want to take advantage of it has greatly decreased.

—Will our saint perform the miracle we are all waiting for?

—That’s what we’re doing.