Caletones, a small town of fishermen and summer houses 52 km from the city of Holguín, near Gibara, is a very strong common denominator in the history of my family. It is that place where happy days followed one another and to which we cling in memories now that some of the family live in other parts of the world.

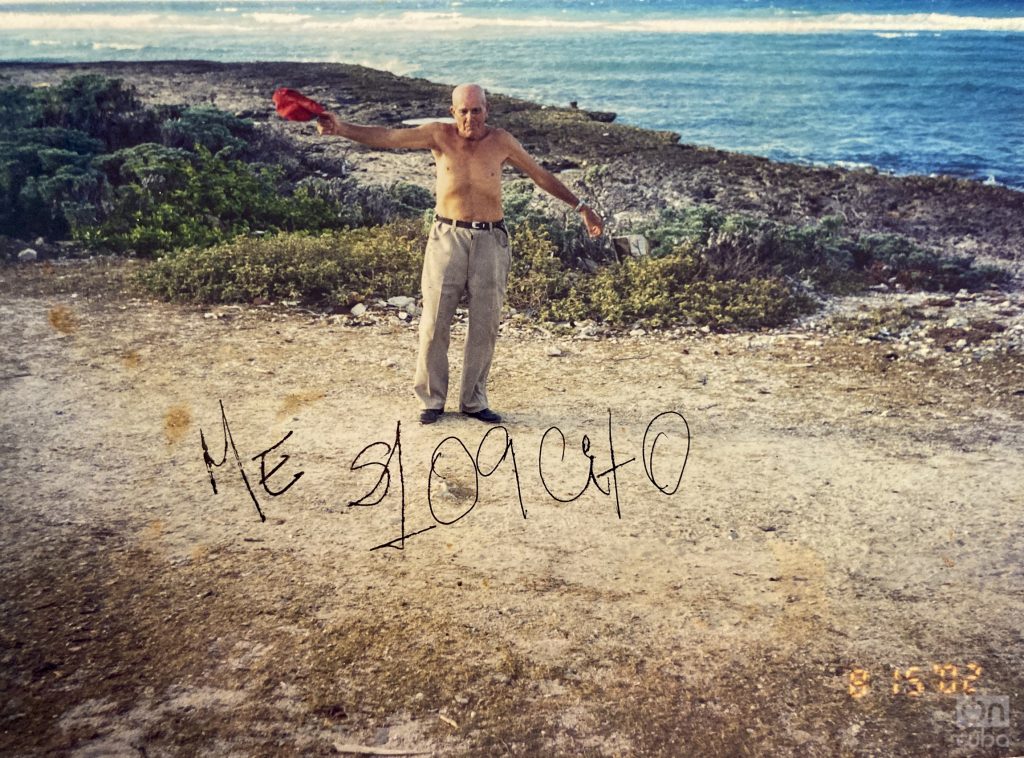

My grandfather Bartolomé arrived at that remote point on the north coast of the eastern region of Cuba one day in 1948. The old man, then a young merchant, fell in love with those places and the kindness of its people. He built a little house and never again in his life did he bathe in another sea other than that of Caletones.

Your children and grandchildren inherit that love. So much so that with pride and honor we proclaim that we are “caletoneros”. That is a kind of category that is acquired solely and exclusively by a sense of belonging to that site.

That is why in the most dissimilar ways I am always returning to Caletones. July and August, the time when we used to go, since then has smelled of the countryside and saltpeter for me. Even though I have lived in Argentina for more than a decade, a country where a harsh winter is raging in those mid-year months, I still think it is summer. Still wrapped up to my head, shivering with cold and in the middle of gray days, I think of those times on the beach, with heat, a withering sun and me rocking in a green hammock, hanging from the doorway a few meters from the sea, caressed by a unique coastal breeze.

Memories like those don’t lose sharpness. It doesn’t matter how many years go by or how sporadic it is —more and more—, my physical return to Caletones due to geographical distance. I keep latent memories of the nights we went to dance in an improvised disco in the only bar in town. It was a place without walls, with cement tables and benches. The only offer at the bar: loose rum and bread with pasta (we never knew what the pasta was). I also have engraved in my memory the walks at night with my mother and my aunts in search of a television to watch the Brazilian soap opera The slave. And domino games? Real championships, in the light of a Chinese lamp, which were set up on the terrace of Carlos Peralta’s house.

The locals of Caletones are also an inseparable part of my endearing imagination. Armandito, a symbol of kindness, is one of them. He lived with his family in a very humble, precarious little house, a few meters from ours. He is the youngest of five siblings. Almost that family subsisted on what they fished day by day.

Mandi, as she is affectionately called, has a different condition than most people. Although I couldn’t say for sure, I think he was born with Down syndrome.

The remote and almost desolate part of the town; the distance from the city, where he could have had specialized attention since his childhood; a complex family context and, above all, the brutality of the not very inclusive society in which we live, made Armandito grow up being the focus of much discrimination.

Heartless and ignorant people referred to him as “Armandito el bobo”. On some occasions I remember that even some of those adults used his figure to instill fear in the little ones. Luckily other people wanted it. They welcomed him and helped him.

And Armandito went around Caletones smiling, without hurting anyone. Always familiar and helpful. One of those summers, when I was 8 or 9 years old, other children older than me tried to snatch a bunch of milkweed from me. I was scared. He was cornered and couldn’t run away. When I was on the verge of tears, Armandito appeared. As a superhero of those who appear in the movies, he prevented such injustice from being committed. Armandito saved me that afternoon.

That day he escorted me to my house. Along the way we went devouring the anoncillos. In each place, each town, however remote it may be, live guardian angels of flesh and blood, to say it in a romantic liturgy. Armandito is without a doubt the one from Caletones.

Years passed. My vacations in Caletones were becoming more and more distant in time. Each one of the family was taking their course towards other geographies. Before he died, my grandfather sold the house or what was left of it, because it was impossible for him to support it. Then a hurricane happened and it was so sinister that it radically changed the appearance of the town.

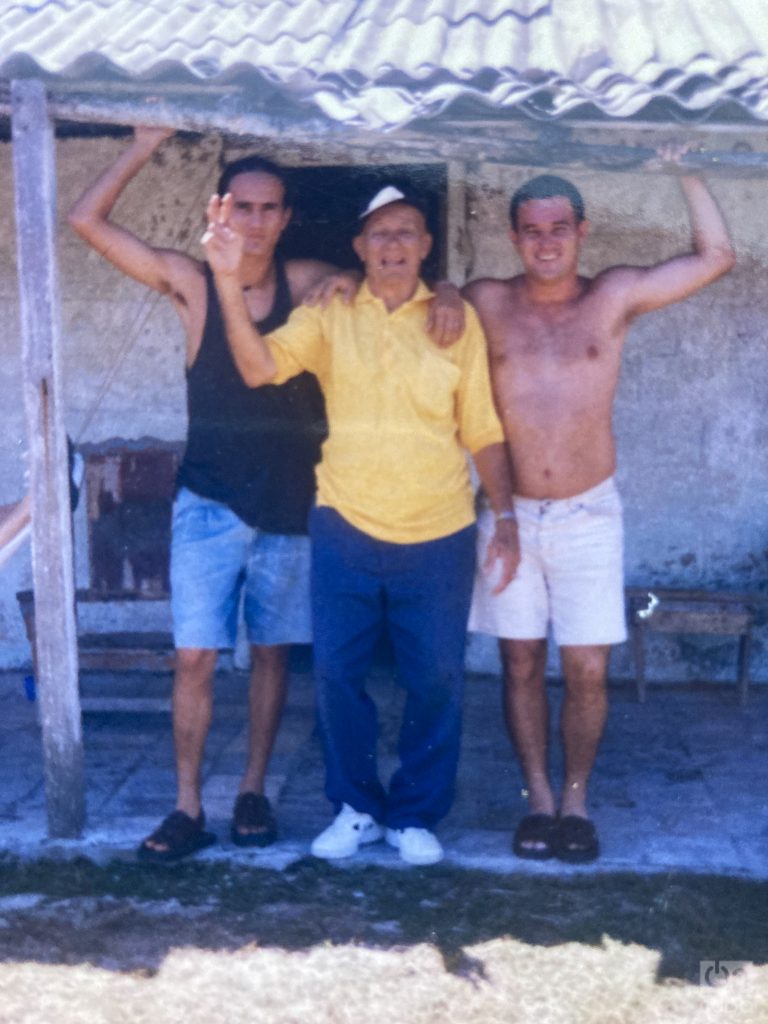

In January of this year we managed to meet with a large part of my family, including the new members. And we returned to Caletones for a few days. It was January, but we felt like we were in July or August.

We were twenty-three. We stayed at the Peraltas’ house, next to where my grandfather’s house was for more than 60 years.

One afternoon Armandito appeared from the coast, walking. There she was, now in her fifties but with the same smile as before. Going to Caletones is definitely like traveling in a time machine to the moments when we were happy.