“I learned to cook cooking and got so much taste for the work that my kitchen was always clean. I had a great care and great care for the kitchen, ”says retired lunch maker Maria das Graças Soares Barbosa, who worked at Maria Polidoro State College in Canoas, Rio Grande do Sul, between 1989 and 2013. who recognize me and say ‘aunt, how good your lunch’.

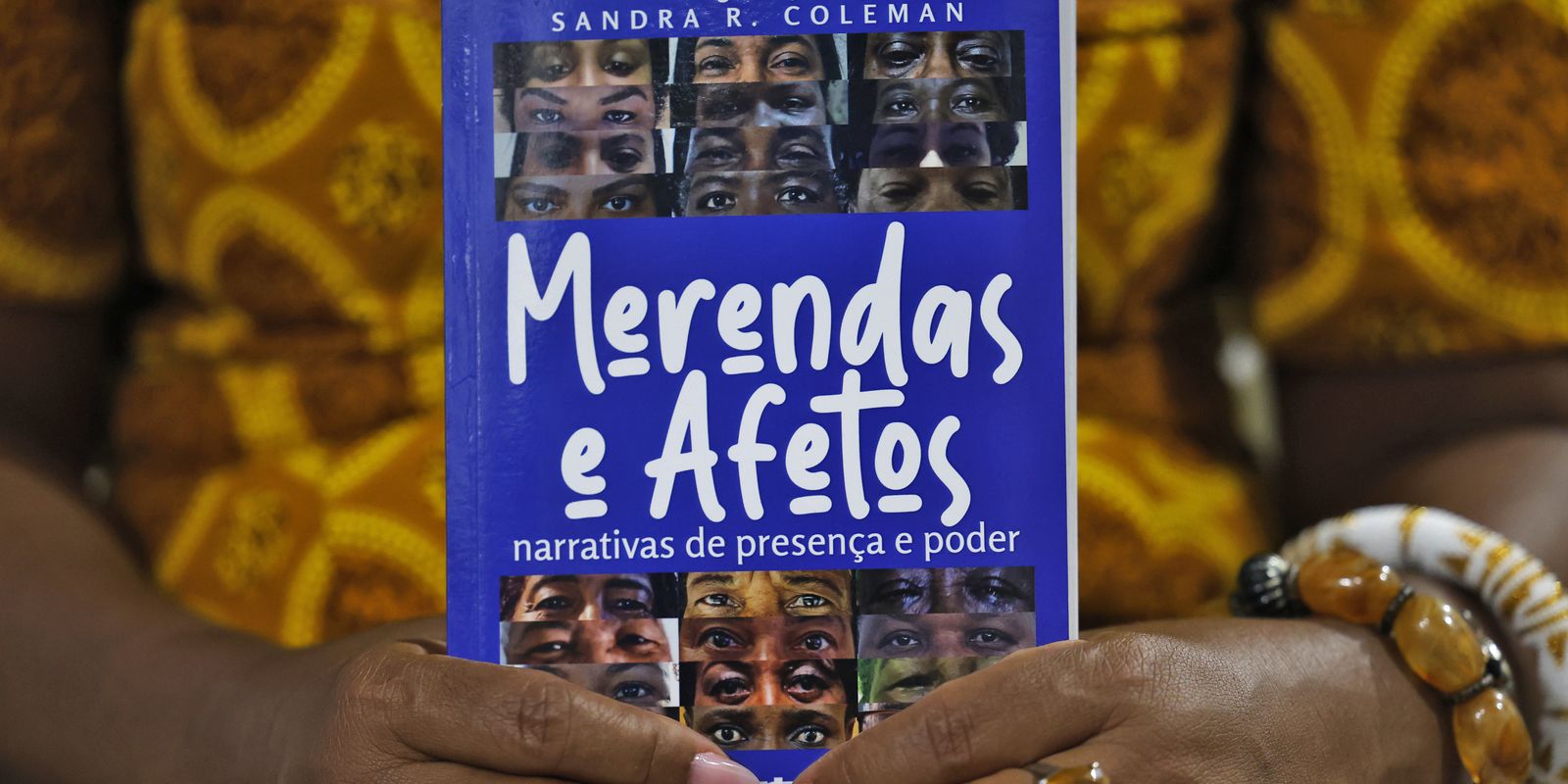

The story of Maria das Graças is one of those that are part of the book Lunch and affectionorganized by Sandra Regina Barbosa Soares Coleman. The publication features 26 biographical narratives, all of black people from different Brazilian states – Bahia, Rio de Janeiro and Rio Grande do Sul – and the Federal District.

The book gathers life stories of 18 black women, one who are often called aunts: the aunt of the lunch, the aunt of the corridor, the gate aunt, the aunt of cleaning. They are employees who usually meet students sometimes better than teachers themselves and are fundamental for the operation of schools.

“Despite not having much study, I treat everyone well, I learned from life,” says another biographed, Fatima Souza de Oliveira, affectionately known as Fatinha, responsible for cleaning the Integrated Center for Public Education (CIEP) 370 – Professor Sylvio Gnecco de Carvalho, in Duque de Caxias, in Rio de Janeiro.

“Being a cleaning aunt for me is rewarding. With students, learning and teaching. Sometimes I feel their second mother. The affection and admiration is reciprocal. I am very grateful for the work I have, ”says Fatima in the book.

Power narratives

The book is the third of Sandra Coleman, also author of Brazilian black women – Presence and Power, from Exhibition to the Book (2020), Children, parents and grandparents – narratives of presence and power (2021). In all works, Sandra brings together narratives of black people, always written by black women. In the third work, the writer turned attention to schools.

“I see these lunch boxes, inspectors, they are invisible, they are invisible to school management. Many, school management or teachers do not know their names, which do not actively participate in school decisions. I believe they know much more about students than teachers because they have a greater conviviality with students, because they are seeing what students are doing in the corridor. When they go to the lunch, the cleaning aunt is there, she is seeing everything, ”says the author of the book.

To conduct the stories, Sandra Coleman elaborated a list of questions to be asked for the biographers – in this work, 24 women and two men. Questions include questions about the history of families, grandparents and great -grandparents, and also about episodes of racism.

“The book brings some characteristics of Brazilian society,” says the writer. “The issue of child labor, many women who started working, children 5, 6 years old, you will find the issue of domestic service, you will find enslavement. In full [ano de] 1950, in the interior, there were still people living in slavery, ”he says.

The focus of Lunch and affectionas the title points out, it is the school lunch. The lunch is considered fundamental in Brazilian schools for the permanence of students in school. Food is even national public policy, implemented by the National School Feeding Program (PNAE), which passes federal financial resources to attend students enrolled in public schools.

“He has [no livro] case of lunch box that did not follow the order of the nutritionist of the city. She said they have mashed potatoes and she made yam puree, because yam is more nutritious. And the children ate mash of yam thinking it was mashed potatoes. So, so they are fantastic, you know? ”, Highlights the author of the work.

Stories of many

Both Mary of Graces and Fatima are history spokesmen lived by many black women. “I suffered racism in one of the houses I worked in, when the boss sister said she didn’t like black people. I just like beans in black, ”says Fatima in the book. She also says that at school she found support: “When I worked in a private school, a student called me a Black Donkey. The director was black, well structured, did not conform, called his parents and made him apologize in front of his parents, and he never did that. ”

According to the Federal Constitution, racism is an unenforceable crime in Brazil. Those who commit the racist act can be convicted even years after the crime. Law 14,532, sanctioned in 2023, increases the penalty for the injury related to race, color, ethnicity or national origin. With the norm, those who give offenses that disrespect someone, their decorum, their honor, their goods or their life may be punished with imprisonment of 2 to 5 years. The penalty may be doubled if the crime is committed by two or more people.

Even in a country where black people represent 55.5% of the populationMaria das Graças says she suffered racism.

“A child poured the lunch on the floor, and the teacher said, ‘Come on, black, cleaning is your service.’ This in front of the children. I swallowed and after serving the lunch I sought Neide, my director, a blessed person who defended me, ”says Maria das Graces in the publication.

Graça states that today is she who defines himself: “If you ask me who I am, I answer: Black, mother, grandmother, carnival, capoeirista and daughter of Oya. I consider myself a true warrior. ”

One climbs and pulls the other

The life experiences of the biographers also resonate in the history of the author herself. By gathering other people’s experiences, Sandra Coleman refills her own narrative. She was born in São Gonçalo, metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro. Poor family, early on, worked helping his mother with household chores.

Sandra says she always dreamed of taking a college degree. From an early age, it was discouraged. “I had the dream of entering university, but around me my friends were all non -black. Because we have this thing today, so they were not black. And they said that college was bullshit, which was full of engineer working as a sweeper. Why was I going to go to college? But they went, ”he recalls.

She went through a series of jobs, and in one of them she was hidden from the owner of the company because he couldn’t know that he had a black employee hired there.

It was at the Palmares Human Rights Institute (IPDH) that his racial conscience “exploded.” There, for the first time, she says she was called beautiful. ok Talking to me? Like this? Beautiful? I? Me, beautiful? ‘ And I got up and went pro Bathroom, look in the mirror. I was like this: ‘peraithe woman said I’m beautiful? As? I?’. Because I never, 38 years old, I had never heard anyone say I was beautiful. “

Sandra realized the dream of going to the university and became a bachelor of arts and master in professional studies, with concentration in multicultural education. In 2005, she met her husband, American lawyer Major Coleman, and today lives in the United States.

The first book was born from an exhibition he made to show the Americans that Brazil has, yes, academic black women, because the students who arrived in the United States were all non-black. It was the exhibition Black Brazilian Women: Presence and Powerat New York State University. Sandra Coleman says she still wants to write seven more books, totaling ten.

In all works, she seeks to tell stories of black people and bring black women together to write, or the story themselves, or the history of other people. “I really believe in one up and pulls the other. I believe in ubuntuI believe in, together, we are stronger, ”he says. Ubuntu is a word of African origin that refers to a philosophy that is based on interdependence between people. It can be translated as “I am because we are.”

The book Lunch and affections: narratives of presence and power can be purchased in website from the publisher Africa magazine and Africanities.