The recognition of Zombie Day and Black Consciousness on November 20th as a civil holiday across the country took a long time: 53 years. The interval is greater than the time between the Eusébio de Queiroz Law (1850), which definitively prohibited the importation of enslaved people into Brazil, and the Áurea Law (1888), which declared slavery “extinct” in the country : 38 years old.

The preference for 20/11 manifested itself for the first time in 1971, during the civic-military dictatorship, and came from a group of black students and activists from Porto Alegre, interested in literature and the arts. They did not consider the celebrations around May 13th, the day of signing the abolition of slavery by Princess Isabel, Imperial Princess Regent, to be appropriate – which formally put an end to around 350 years of black slavery in Brazil.

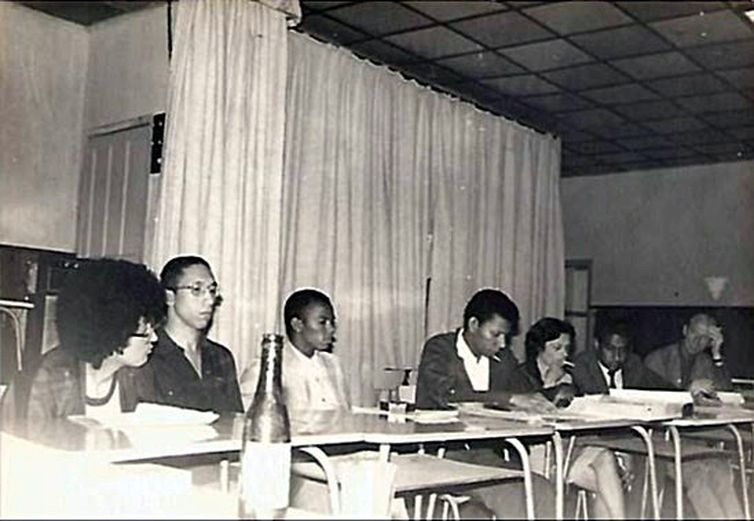

The collective of black boys, formed in July of that year, was later called Grupo Palmares and was made up of Oliveira Ferreira da Silveira, Ilmo Silva, Vilmar Nunes and Antônio Carlos Cortes. Cortes, today an experienced lawyer specializing in civil and criminal law and the only living person from that original formation. According to him, Luiz Paulo Axis Santos and Jorge Antônio dos Santos also belonged to the “informal group”, who had a more discreet role.

There were six of us, but four showed up and two remained hidden, as our strategy, because if the dictatorship eliminated us, these other two would continue”, recalls Antônio Carlos Cortes in an interview with Brazil Agency. Over time, the composition of the group changed, including the entry of women.

“The small group of black people usually met on some late afternoons at Rua da Praia (officially, dos Andradas), almost on the corner of Marechal Floriano, in front of Casa Masson”, described the poet Oliveira Silveira, already trained in Literature at the time, in an article signed on October 17, 2003 and published in the book Education and affirmative actions: between symbolic injustice and economic injustice.

According to the text, in the group Jorge Antônio dos Santos was “the most vehement critic” of May 13th, but there was unanimity in the group against having that date as a historical reference for the fight for freedom for black Brazilians.

“13 was not satisfactory, there was no reason to celebrate it. Abolition had only occurred on paper; the law did not determine concrete, practical, tangible measures in favor of black people. And without the 13th, it was necessary to look for other dates, it was necessary to return to the history of Brazil”, noted Oliveira Silveira.

References

According to him, who also became a theater author, the group knew the play Arena counts Zombie, by Gianfrancesco Guarnieri and set to music by Edu Lobo (1965). Zumbi dos Palmares was also on newsstands, in issue number 6 of the series Great Characters of Our Historyedited by Abril Cultural. The publication listed November 20, 1695 as the date of Zumbi’s death.

At the Public Library of the State of Rio Grande do Sul, then student Antônio Carlos Cortes located the book Palmares Quilombo (1947), by historian Edison Carneiro. The book corroborated the date of 20/11, as well as other books consulted later by the group such as The wars in Palmares (1938), by the Portuguese historian Ernesto José Bizarro Ennes, and Palmares – the black guerrilla (1965), by the Gaucho historian Décio Freitas and initially published in Uruguay.

In addition to the date of Zumbi dos Palmares, the group planned to pay tribute to lawyer Luiz Gama on August 24, and to journalist José do Patrocínio on October 9, the birth dates of the two black abolitionists. “A precarious but deliberate political action was outlined in order to present, to the black community and society in general, alternatives of dates, facts and names, in challenge to the officialism of May 13th”, explained Oliveira Silveira in an article.

Prior censorship

The first tribute articulated by Grupo Palmares to Zumbi took place on 11/20, a Saturday night, at Clube Náutico Marcílio Dias, with the event Zumbi, the tribute to black theater. Before the presentation, on the 18th, the group was called to the Federal Police headquarters to detail the event’s schedule and obtain censorship clearance.

“All of our demonstrations had to go through the Federal Police, through censorship, so that they could stamp it authorizing that act that we were going to carry out in light of the 20th of November in Zumbi dos Palmares. More than that, Oliveira and I ended up being detained”, recalls Antônio Carlos Cortes about the forced testimony they had to give.

The political repression wanted to find out whether the Palmares Group had links with the organization Vanguarda Armada Revolucionária Palmares (VAR-Palmares), which was active in the armed struggle.

Released to pay homage, on the day of the event, the members of Grupo Palmares and the audience at Clube Náutico Marcílio Dias formed a circle to learn about and discuss the history of Palmares and its quilombos based on studies carried out by students and activists, defending the option for November 20th, instead of May 13th, as a historical date for black Brazilians.

From then on, “Oliveira never stopped doing some activity on the 20th of November for a year”, remembers the actress from Rio Grande do Sul Vera Lopes – from a young age active in the black movement in Porto Alegre. For her, the date of Zumbi dos Palmares’ death “is a reference that refers to what we have always, always experienced, which is the fight for a dignified life. At no point in history did black people willingly accept being enslaved. The entire time, there was resistance.”

Set of quilombos

Minas Gerais historian and professor Marcos Antônio Cardoso, a specialist in the black movement, assesses that Zumbi and the Palmares quilombo have other important attributes. “This was the first collective form of organization of Africans in Brazil against the slavery regime. It was a cultural, political and social experience.”

Palmares, in fact a group of quilombos that existed for around a century in Serra da Barriga in the captaincy of Pernambuco, today in União dos Palmares (AL), went beyond the predominant cultivation of just one agricultural crop, as happened in sugarcane mills of sugar, and had more horizontal forms of command and leadership than the slavery model.

Zumbi, born in Palmares, but raised in Recife by a missionary priest, returned to the region and later assumed leadership of the quilombo, succeeding, around 1680, Ganga Zumba – who had accepted a proposal of surrender and peace from the Portuguese crown.

Fifteen years after Zumbi assumed leadership of the Quilombo de Palmares, maintaining resistance, the São Paulo bandeirante Domingos Jorge Velho invaded and destroyed the quilombo’s main settlement (Mocambo do Macaco) in 1694. Zumbi survives for about two more years in another stronghold, until he is killed on November 20 by Captain Furtado de Mendonça. With his body dismembered, Zumbi had his severed head exposed in Pátio do Carmo in Recife.

Utopia of equality

For Marcos Antônio Cardoso, despite Zumbi’s defeat and death, “the process of resistance, of guerrilla warfare, of organization, is very important from the point of view of thinking about the history of Brazil from the perspective of the so-called vanquished. The Palmares quilombo is given new meaning in Brazilian black memory. It becomes the utopia of building a society based on equality.”

The gesture of the Palmares Group in Porto Alegre in defending the replacement of May 13th celebrations with November 20th, at the height of repression, did not have an immediate political mobilization purpose. But, in 1978, when civil society began to articulate itself again amid the “slow, gradual and safe” opening of the civic-military dictatorship, the 1971 flag of the small collective from Rio Grande do Sul was embraced by the Unified Black Movement (MNU),

“Thanks to the commitment of the MNU, expanding and deepening the proposal of the Palmares Group, the 20th of November became a political act of affirmation of the history of black people, precisely in which they demonstrated their ability to organize and propose a society alternative”, described intellectual and activist Lélia Gonzalez in the article The Unified Black Movement Against Racial Discrimination.

In his opinion, “Palmares was the authentic cradle of Brazilian nationality, as it established effective racial democracy, and Zumbi, the living symbol of the fight against all forms of exploitation.”

Causes proposed, articulated and embraced by the MNU, such as 20/11, guided the redemocratization of Brazil and even became current public policies, such as the teaching of African history in Brazilian schools, demanded since the late 1970s.

In 2003, November 20th was included by law in school calendars. In 2011, the date was officially established. Last year, also by law, it became a national holiday – after the states of Alagoas, Amazonas, Amapá, Mato Grosso and Rio de Janeiro and around 1,200 municipalities had already welcomed the date as a day without work, but with social reflection.

“It is a fundamental holiday for us to dream of one day being a first world country. We will only be a first world country when we put an end to this plague of racism, prejudice and discrimination”, says senator Paulo Paim (PT-RS), rapporteur of the bill that transformed Zombie and Black Consciousness Day on a national civic holiday.

Black people make up the majority of Brazilians. Black and brown people represent 55.5% of the population – 112.7 million people in a universe of 212.6 million. According to the 2022 Census (IBGE), 20.6 million (10.2%) identify themselves as “black” and 92.1 million (45.3%) identify as “brown”.

According to Paulo Paim, “every black person has to understand that they are descendants of quilombolas, and the principle of quilombos is this: a nation for everyone.”