On a national scale, the total loss amounted to 118,779 jobs, a severe shock for a sector that promised a new era with the relocation of companies.

In the north of the country, several forces intersect that put pressure on the labor structure. Automation replaces operators with mechanical arms. The wage increase on the border reduces margins. And U.S. tariffs inject uncertainty into every container that crosses customs. Added to this is the Mexican inspection, which keeps hundreds of companies from the IMMEX program suspended.

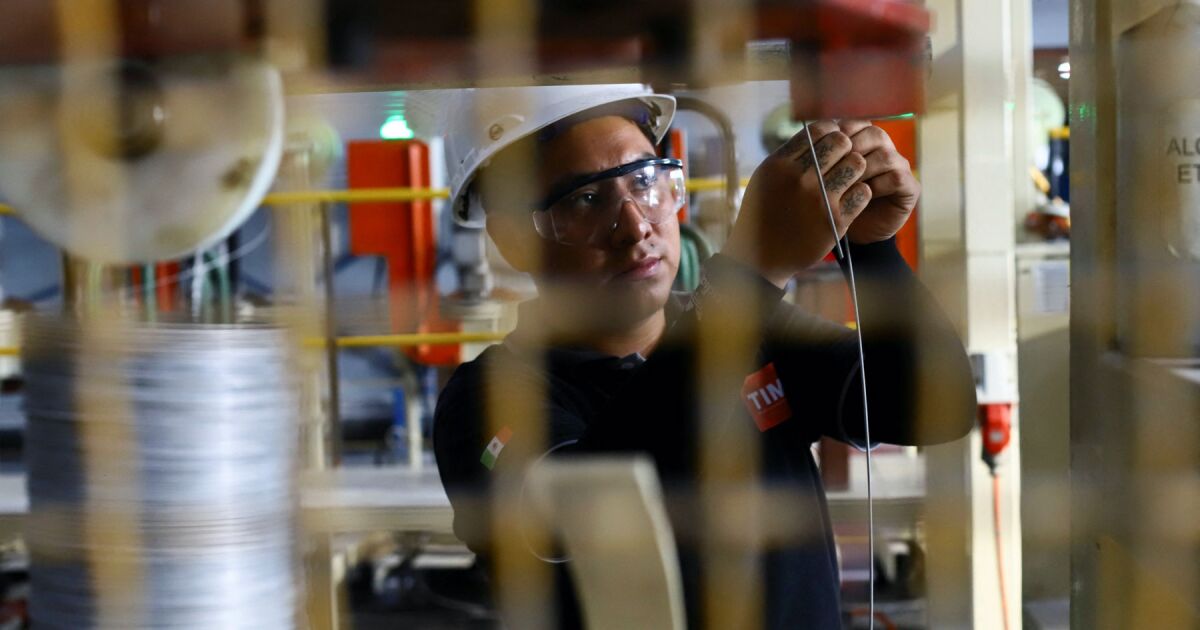

Robots online

From Ciudad Juárez, the local Coparmex confirms the change. Automation and Artificial Intelligence alter the traditional maquila. Collaborative robots and predictive maintenance systems increase productivity and reduce costs, but they also displace workers. In the region, technology became a key factor in job losses by taking over repetitive tasks.

Although modernization boosts competitiveness, it leaves a void: the lack of training. Edelman’s 2025 Confidence Barometer reveals that 72% of Mexicans perceive a lack of technological skills as a threat to their job security, second only to the recession and trade tensions.

The National Council of the Maquiladora and Export Manufacturing Industry (Index) recognizes the impact, although with nuances. The phenomenon does not respond only to layoffs, but also to replacement by specialized workers, capable of operating and supervising new production lines.

A rising salary

The minimum wage on the northern border reaches 419.88 pesos per day, above the national average of 374.89 pesos. Government policy aims to maintain the increases throughout the six-year term. For companies, wage pressure is combined with rising input costs and economic volatility.

In 2025, the minimum wage is equivalent to 8,480 pesos per month in almost the entire country, with the exception of the Northern Border Free Zone, where it amounts to 12,771 pesos, according to Conasami. Since 2019, the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador began a policy of aggressive increases. “Nothing that the workers are going to be exploited in the maquiladoras,” the president said then. That year the increase was 100%.

The closure of the Wrangler plants in the Comarca Lagunera reflects the consequences. The textile firm, with 25 years in Mexico, closed its operations in Torreón, La Rosita, Coyote and San Pedro, Coahuila. More than 3,600 employees were left without work. The director of Economic Development in Torreón, Antonio Hernández, explained that the measure responds to a global restructuring motivated by high operating costs and the intention to concentrate production in countries with lower salaries.

The minimum wage on the northern border is equivalent to about $680 a month, a figure higher than that of many provinces in China, the manufacturing center of the world. In Shanghai, for example, the minimum monthly wage reaches $378.

Duty

The sector faces a distorted environment that the Index itself describes as a “loosening.” “Mr. (Donald Trump) releases the tariffs and then retracts them. Thus we live in constant uncertainty. Companies stop decisions until they understand what the real situation will be,” recognizes its national president Humberto Martínez.

Grant Thornton’s International Business Report confirms the tension. Mexican manufacturers operate under pressure from new tariffs, while costs and uncertainty increase. Business concern about the economy went from 42.4% in the first quarter to 56.2% in the second.

In IMMEX companies, tariffs and rising input prices create a double challenge: sustaining export competitiveness and adapting to an increasingly regulated environment. Even so, the sector retains room to transform through technological adoption and market diversification.

Under scrutiny

The IMMEX program, the cornerstone of the Mexican export model, is going through its own crisis. Created to allow temporary duty-free imports, as long as the products were processed and exported, it became vulnerable to abuse. Part of the inputs ended up in the domestic market.

The Ministry of Economy tightened supervision. In 2025, more than 670 companies were suspended, with audits focusing on the textile, clothing and footwear sectors, where smuggling dominates more than 70% of the market. Secretary Marcelo Ebrard warned that the program needs cleaning: every year about 300 companies were canceled, but in 2025 the figure doubled.

The purpose is not to eliminate the program, but to preserve its value. However, the transition is difficult for an industry facing a perfect storm: automation, wage pressure, tariffs and fiscal surveillance. Mexico seeks to maintain its role as a manufacturing epicenter, but the industrial pulse of the north beats with a lower intensity today.