Christian Nielsen

“The republic does not need scientists. The action of justice cannot be stopped.” Hearing this sentence, the executioner of Paris released the blade of the guillotine and his head fell into a basket bathed in blood. A few steps away, the Italian physicist, mathematician and astronomer JL Lagrange would pronounce this response: “It took a moment to cut off his head. Not even a hundred years will be enough to give another one like it”.

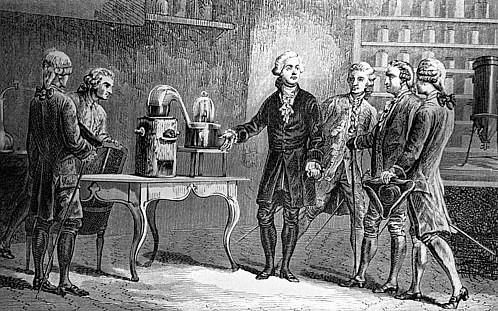

It was May 8, 1794, 228 years ago today. The head that lay at the foot of the gloomy guillotine was that of Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier, a French chemist, biologist and economist considered the father of modern chemistry. His contributions to research and the scientific method were so many and so relevant that it would be impossible to list them all at once.

Lavoisier was 50 years old when he was taken to the gallows in the Plaza de la Revolución, now Plaza de la Concorde. But what had the scientist done to deserve such a death?

MONARCHISTS IN THE SPOTLIGHT – Lavoisier was a member of the French Academy of Sciences founded in 1666 to “encourage and protect the spirit of research and contribute to the progress of the sciences and their applications.” The Parisian had already recorded a series of discoveries and statements that were completely revolutionizing the world of research.

Almost nothing: studies on the oxidation of bodies, the phenomenon of animal respiration, the analysis of air, the law of conservation of mass or Lomonosov-Lavoisier law, the physical characteristics and behavior of heat and a very detailed description of chlorophyll photosynthesis. By 1789, the year of the revolution, Lavoisier was one of the most prestigious scientists of his time, but he was also considered a committed monarchist who was being targeted by the revolutionaries. To make matters worse, he had married the daughter of one of the owners of the company in charge of collecting taxes called Ferme Generale, a royal concession originating in the seventeenth century.

But it was not these characteristics of his multifaceted personality that attracted the revolutionary ray that would end his life, but rather something more pedestrian and not very republican: envy.

ACADEMIC INTRIGUES — Jean-Paul Marat was a French scientist and physician who spent much of his youth in England. But the outstanding stretch of his life was lived as a journalist and politician at the service of the French Revolution. In 1780 he applied for his admission to the Academy of Sciences by submitting a paper called “Physical Investigations on Fire”.

The academic faculty ruled that the study lacked scientific value and Marat’s membership was rejected. The frustrated academic attributed the slam to Lavoisier. Years later, having become one of the most fearsome leaders of the revolution, Marat took his revenge by raising an accusatory libel before the Public Health Committee against his supposed objector whom he described as a charlatan, a companion of tyrants, a disciple of rogues and an enemy. of the revolution.

Too many charges and too heavy for the Committee to ignore in the midst of the reign of terror that was swallowing revolutionaries one after another. Thus Robespierre succumbed, guillotined two months after Lavoisier, Danton, fell under the knife a month before the scientist and Marat himself, murdered in 1793 by Charlotte Corday, a Girondin activist who stabbed him while the polemicist was taking a bath.

IMMENSE LEGACY – Lagrange’s words before the decapitated corpse of his friend and colleague were prophetic. It would be a long time before a mind of such brilliance lit up the world of scientific inquiry.

Lavoisier was not a mad scientist locked in his laboratory among alembics, crucibles and pipettes. He was a rigorous observer of nature, something impossible to achieve from a laboratory cloister.

“I consider nature as a vast chemical laboratory in which all kinds of synthesis and decomposition take place” stated who would later describe chlorophyll photosynthesis very precisely in these terms: “During the hours of sunlight, a plant absorbs carbon from the carbon dioxide and at the same time throws off only the free oxygen and keeps the carbon for itself as food. This, which is taught today at school and studied in depth at university, was a novelty in those turbulent days.

And as expressly contradicting whoever handed him over to the executioner, Lavoisier left this thought about charlatans and true scientists.

“The art of concluding from experience and observation consists in evaluating the probabilities, in estimating whether they are high enough or numerous enough to constitute proof. This type of calculation is more complicated and more difficult than one might think. It demands great sagacity generally above the power of ordinary people. The success of charlatans, sorcerers and alchemists, and of all those who abuse public credulity, is based on errors in this type of calculation.

And he concluded: “We are scientists and we should not trust anything but the facts.”