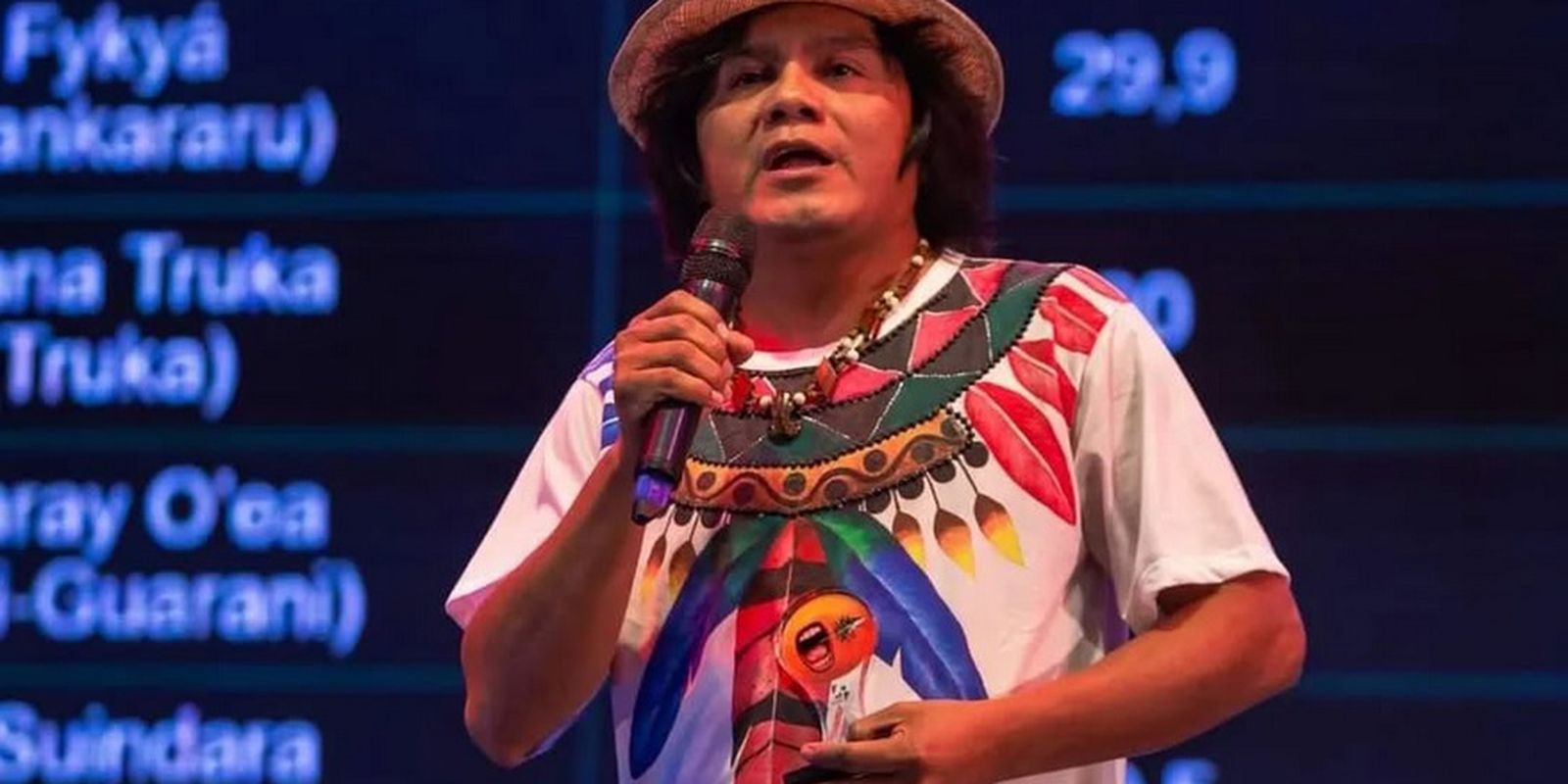

“The whole village burns down / In the sunny morning in the forest. / There’s fish roasting on the fire / And cupu juice to complete the party.” The verses written by Tiago Hakiy (featured photo), indigenous poet and writer, allow the reader to enter the heart of the Amazon rainforest and feel part of it. For a few moments, we are part of the party, we dance, we taste fish and juices typical of the region. The excerpt above is part of the book Poetic ABC of the Forestreleased in November. The work both presents the secrets of culture to laypeople and welcomes local spirits.

“At school, I always found books that had nothing to do with my reality. They talked about sharks and I’ve never seen sharks. They talked about fruits, like apples and strawberries, which I had never eaten. About fish that were not part of our Amazonian fauna. I felt lost in this literature. When I write today, I think about the boys and girls born in the middle of rivers and forests, who ride canoes. So that they can identify with their own reality”, says the poet.

Tiago Hakiy’s writings did not always follow this path. Belonging to the Sateré-Mawé people, he was born in the Freguesia do Andirá community, in the municipality of Barreirinha, in Amazonas, far from editorial spaces and large urban centers. At the age of 6, a writer came to the community and helped him discover the world of books. At 19, he moved to Manaus, where he entered university and had the opportunity to publish his first book of poetry.

The initial verses did not talk about his cultural reality and that of the indigenous people. They were more idyllic poems. Everything changed when he met the writer Daniel Munduruku, a precursor of indigenous literature in Brazil.

“He said to me: ‘James, why don’t you write about your people and your origin? If we don’t continue writing about our people, cultural erasure will continue to happen’. He encouraged me to remember my entire ancestry. And from then on, poetry began to highlight our wealth as indigenous people of the Amazon Forest, our exchanges and care for it, which is everything to us. It gives us food, shelter, paths and inspiration”, recalls Tiago Hakiy.

The indigenous poet is now 44 years old and has 17 published works. And participation in several anthologies, which he values highly, as he understands that collective work is an important characteristic of indigenous communities. It was with the anthology Apytama, organized by Kaká Werá, that he collectively won the Jabuti Prize in the Youth Book category.

“Indigenous peoples are the result of orality. I was born hearing stories from my elders. Naturally, we learn to tell stories that we have heard since we were children, and these stories are an instrument for learning, not just for entertainment. They are a way of teaching and transmitting knowledge”, highlights the indigenous writer.

Tiago Hakiy also today understands poetry as a political instrument, capable of generating empathy from other people and engaging them in the fight for the rights of indigenous peoples and the preservation of the forest.

“Literature serves as a flag so that people can get to know us better. Our culture and tradition, which are neither better nor worse. Just different. And we want to be heard, understood and respected”, he says. “We want these people to also take care of our rivers, our trees, our birds. That’s why, when we call for the preservation of the forest, we know how important it is not only for Brazil, but for the entire planet. We need everyone to have this sensitive look at the people who live inside the forest.”

Parintins Festival

June is a month of celebration in the Amazon. In Parintins, state of Amazonas, almost on the border with Pará, the Bumbódromo hosts the Bois Caprichoso and Garantido parades. It’s the duel of blue and red, which lasts three nights. The show stands out for its colors, lights, costumes, props, dances and music. But the impacts are not just aesthetic and sensorial.

“The two oxen have been bringing important messages, such as the emergency of the climate crisis, the focus on the Amazon, the preservation of traditional peoples. All of this has to be included in the festival”, explained Marciele Albuquerque, indigenous of the Munduruku people and cunhã-poranga of Boi Caprichoso, during TEDxAmazônia 2024, an event held between the end of November and the beginning of December, in Manaus.

According to tradition, the cunhã-poranga is “a beautiful girl, warrior and guardian, who expresses strength through beauty”. She is evaluated by the judges on criteria such as beauty, friendliness, clothes and movements. But Marciele guarantees that her attributes at the festival go far beyond being a beautiful woman.

“When we go to the arena, we want to do more than just a performance, a difficult dance move, something spectacular. We really want to protest through our dance, our gaze, our power and strength. It’s going far beyond the physical part of women. We carry this ancestry. I’m not just an act. I am indigenous, Cunhã-Poranga. My body is political. It’s strength. It’s ancestry”, says Marciele.

Born in Juriti, Pará, she has lived in Manaus for over 13 years. She has a degree in administration and has been an activist against climate change, hunger and the future of the Amazon. He has already participated in the United Nations (UN) Climate Week in New York, United States, in 2023. And, in the same year, he was at the Youth for Climate Conference, promoted by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. Agriculture (FAO), in Rome, Italy.

“Art awakens political sense. You start to question and seek answers. You start to want to fight for something. That’s how I woke up, it wasn’t because someone came to talk to me about traditional politics. Through art I managed to have this very critical sense, to awaken to this collective struggle. Even if I don’t suffer from a certain situation, others may be suffering and I will fight for them. Art has the power to unite. This, in a lighter way and capable of puncturing blisters”, argues the cunhã-poranga.

Trans amazon

The body also has a political dimension for Maria Flor, 25 years old, born and raised on the banks of the Tapajós River, in Santarém. Peripheral transvestite, artist and environmental activist, she defines her own body as “territory and communication tool”. Through fashion, street performances, presentations and parades, she connects artistic practice with the rights of transgender people and the people of the Amazon.

“I started around 2016 doing body interventions from a trans-centered perspective. That’s when I understood myself as a transvestite. The first interventions were bodily experiments through clothing, recognizing myself as a female identity”, says Maria Flor.

“I lived near a beach and my concerns began there. I saw a lot of degradation, ferries and ships coming from abroad, taking water from our rivers. Along BR-163, which runs through Brazil, I saw a lot of soybeans, corn, tree logs, wood, bauxite, iron leaving Santarém. Everything that was extracted from within the forest. That was when I started making visual interventions, through photos and videos about this territory that was being polluted”, says Maria Flor.

In this context, Mulambra emerged, one of the activist’s names and artistic identities, which would also give its name to the clothing brand she created, Mulambra Grif.

“I mixed environmental issues with the perspectives of the body as territory and identity. I understood that Mulambra was an ancestral energy that came to question the situations that happened there. The extent to which a mining house on the edge of the city and a transvestite body were naturalized, no. This person was demonized, expelled from home, without access to health and education services, without space in the formal job market”, he says.

One of the artist’s verses is very representative of this impulse of struggle and activism connected to Amazonian nature: “Revolted / Engered / Appropriated the entire forest / In the spine of the cuandú / In the grip of the sucuriju / In the poison of the surucucu / In singing of uirapuru / In the magnitude of its King vulture / In the strength of sussuarana / In the cry of a howler monkey / In the distrust of the agouti / In the claws of a hawk.”

Maria Flor has lived in Belém for three years. Manual printing has become a symbol of resistance, awareness and empowerment. Unique pieces, produced by hand and inspired by the fauna and flora of the Amazon, became a manifesto against deforestation and pollution. In addition to recycled materials, the artist uses recycled elements and even materials found in tree bark.

“Latin America is often seen as a place to discard clothes that were not sold in Europe. I start from a peripheral perspective, from the pedagogy of trash. All I do is rebuild ready-made clothes, going to thrift stores, getting second-hand items, or from disposal sites. I reconstruct the fabrics through printing and tell other stories”, explains the artist. “I make sure people know where everything we’re wearing comes from. Many, without realizing it, buy things that are financing mining and deforestation in the Amazon. All of this is tied together in a certain way as communication and artistic performance.”

Series about the Amazon

The report is part of the Amazon Trails serieswhich opens the year of the 30th UN Conference on Climate Change (COP30), to be held in Belém, in November this year. In articles published in Brazil Agencypeople of the Amazon and those directly engaged in defending the forest discuss the impacts of climate change and responses to deal with it.

* The team traveled at the invitation of CCR, sponsor of TEDxAmazônia 2024.