This is how the American media ‘The Hill’ describes the panorama that exists in Cuba.

MIAMI, United States. – An opinion article published in the American media specialized in politics The Hill maintains that, while Venezuela “wobbles,” Cuba “begins to fall,” and describes a panorama of widespread blackouts, monetary collapse, sugar collapse, and unprecedented migration.

“The drama may be minor, but the danger is real. If Venezuela falters, Cuba begins to fall,” writes analyst Daniel Allott in the column titled “Venezuela is collapsing — and don’t look now, but so is Cuba” (in Spanish, “Venezuela collapses — and be careful: Cuba too”).

Allot recalls that on September 10, “Cuba’s entire electrical network failed, plunging almost 10 million people into darkness” and that this was “the fourth national blackout in less than a year.” Likewise, he attributes the deterioration to “years of inattention” and the use of high-sulfur crude oil that has “crippled” the plants, in a context in which “fuel shipments from Venezuela—Havana’s economic lifeline for two decades—now fluctuate abruptly, sometimes falling below 10,000 barrels per day before rebounding.”

The journalist also notes that Russia and Mexico They have sent shipments of hydrocarbons, but “none offers stability.”

The article also describes the daily impact of the energy crisis and shortages: “In some towns, residents cook by candlelight, charge their phones at work and sleep on rooftops to escape the heat.”

In parallel, it portrays the collapse of purchasing power: “The dollar is quoted on the street at 400 Cuban pesosthe weakest level on record,” while “average state salaries are equivalent to less than $20 a month at the informal exchange rate.” He also notes that a “two-speed economy” is growing in which access to foreign currency—and not work or skill—“determines who eats well and who doesn’t.”

Likewise, the column highlights the magnitude of the sugar decline: “This year’s sugar harvest is expected to fall below 200,000 tons, the lowest since the 19th century.” In contrast, he recalls that “in the 1980s, harvests exceeded 8 million” and that today “Cuba is importing raw sugar,” which he describes as an “amazing investment” for a former “agricultural superpower.”

Regarding the relationship with Caracas, Allott maintains that the “revolutionary link” between Havana and Chavismo “is eroding.” He assures that “Venezuelan oil shipments to Cuba have plummeted, from approximately 56,000 barrels per day in 2023 to just 8,000 in June 2025.” According to the text, both governments “prop up each other with waning strength—two exhausted revolutions clinging to the same fading ideology.”

The column also points to a deterioration of social services and greater political coercion: “In both countries, force has replaced persuasion. Independent journalists are imprisoned, critics are harassed and citizens whisper their frustrations in private.” Allott summarizes the state of social programs in a blunt phrase: “All that remains are schools without teachers, hospitals without medicines, clinics without electricity.”

As an indicator of demographic bleeding, the author states: “In the last four years, approximately two million Cubans—almost 20% of the Island’s population—have fled.” The departure of professionals affects hospitals, universities and businesses, while “families remain dispersed, classrooms empty and innovation stagnant.”

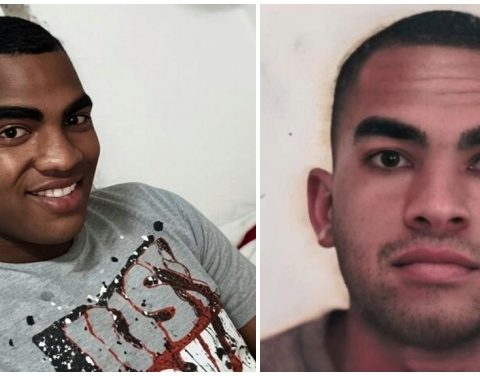

The text also includes statements by the Cuban dissident and former political prisoner Óscar Elías Biscetwho equates the nature of both regimes: “Cuba and Venezuela are twin dictatorships that support each other through corruption and transnational crime.” According to the quote, “the Castro communist regime de facto occupies the political and military institutions of Venezuela and uses them to export repression and traffic drugs to the United States.”

Allott describes political command in Cuba as concentrated in a historic elite: “Formally, President Miguel Díaz-Canel leads Cuba. In reality, decisions continue to flow from a small group of aging revolutionaries—Raúl Castro, now 93, and some long-standing comrades in their nineties,” and asserts that the slogan of “continuity” means for many Cubans “continued suffocation.”

The column places this picture on a regional board where “Washington is once again engaged in a high-risk game in the Caribbean,” with “American warships patrolling off Venezuela” and destroying vessels suspected of drug trafficking as a “show of force” to pressure Nicolás Maduro.

Despite the seriousness of the diagnosis, the author introduces a nuance: “To be fair, Cuba is not Venezuela. Its security forces remain disciplined. Tourism and remittances still bring in dollars that Caracas can only envy. Emigration prevents anger from boiling. And the Communist Party has survived so many shocks that it is always risky to predict its collapse.”

In conclusion, Allott warns that the Cuban deterioration could have greater hemispheric repercussions than the Venezuelan one: “The flickering lights of Havana could be the hemisphere’s next alarm signal.”