From 1960 to 1962, some 14,000 Cuban children between the ages of 6 and 12 arrived in Miami alone, without their parents. Organized by the Central Intelligence Agency in coordination with the Catholic Church and other actors, Operation Peter Pan, as it is known, was one of the most devious incidents of the Cold War and of the collision course between the United States and Cuba since 1959. .

Safeguarding these Cuban minors from a supposed forced expatriation to the Soviet Union was one of the mantras of the Operation. The peculiar context was marked by the Literacy Campaign and the closure of Catholic schools; facts that, incorporated by psychological warfare, had a direct impact on various sectors of the population. In particular, it influenced middle-class parents who perceived that the idea of parental authority was in crisis and therefore took on the task of protecting their children by sending them to destinations that were not always prefigured in the United States.

Operation Pedro Pan began on December 26, 1960 and ended on October 23, 1962, when commercial flights between the United States and Cuba were suspended.

John A. Gronbeck-Tedesco, associate professor of American Studies at Ramapo College, New Jersey, has recently ventured into the history of those events. He just published his book Operation Pedro Pan. The Migration of Unaccompanied Children from Castros’ Cuba (2022), with which he joins a trend aimed at investigating, from academia and from different angles and approaches, the past and present impacts of what is considered the largest exodus of unaccompanied minors recorded in the Western Hemisphere. .

Operation Peter Pan (OPP) accumulates a good amount of studies and research about its motivations, characteristics, implications, and even the traumas it caused. How is this new book of yours different from the others? In other words, why and what did you write it for?

I wanted to create a larger historical context for this story. I draw a lot from that context; but I present new information.

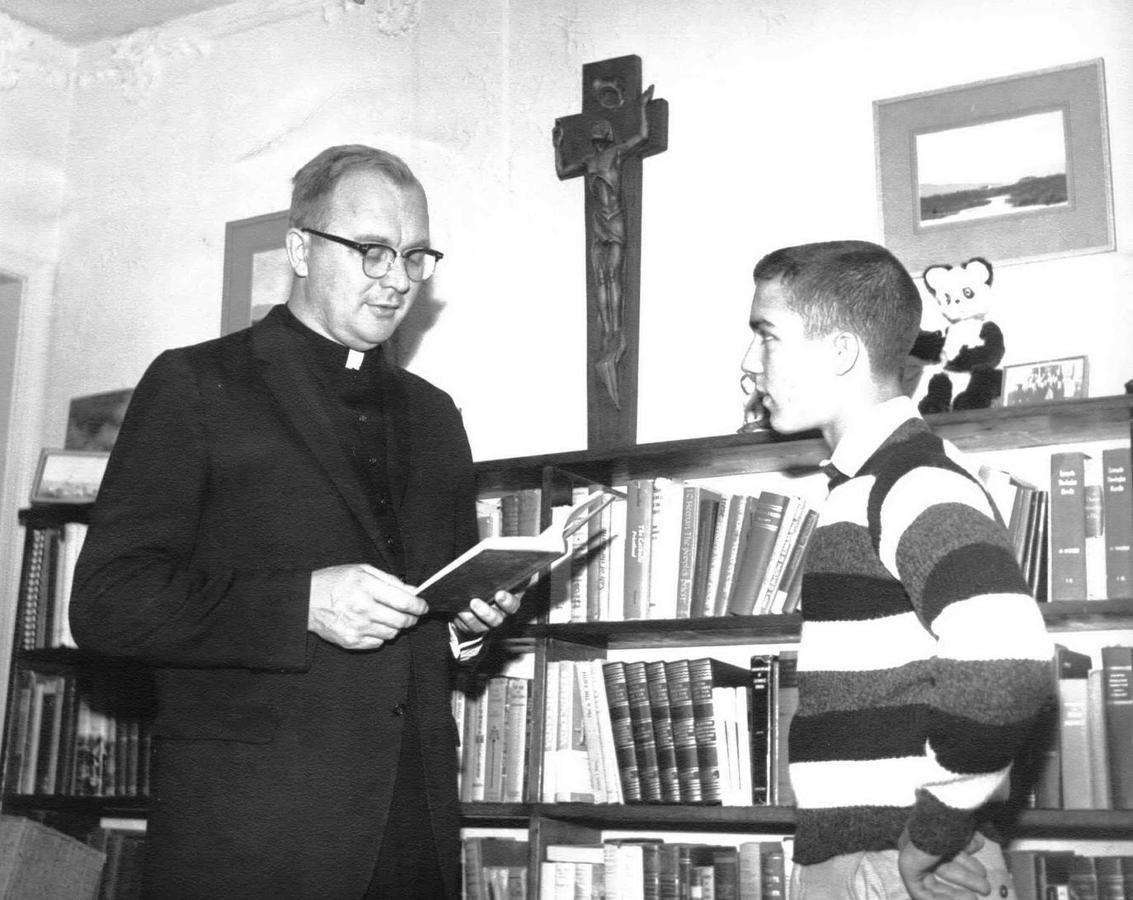

First, I spent many hours researching the Monsignor Bryan Walsh archive at Barry University to find out more about the administrative logistics of the program.

The United States government, the state of Florida, transitional shelters in Miami, and Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish foster homes and groups across the country were involved in caring for the children. It took time, money, legal resources, and the contributions of thousands of people to make it work.

Second, I further explore how child welfare was changing in the United States during the Cold War. There was a movement, for example, to make more use of foster homes instead of group homes (orphanages). There was concern about raising “proper” American children to fight communism.

The ideal of American superiority was increasingly measured in the home environment, with the belief that American families were superior to those of the rest of the world, and that raising the children of the world, especially those from communist countries, it was a Cold War imperative.

Third, I explore in much greater detail how Cuban refugees, including children, became new racial subjects in the United States. The OPP arrived before the categories were made official latino/a either hispanic. Miami, a southern city, was in the midst of its own civil rights movement when tens of thousands of Cubans suddenly turned up.

The majority were white in Cuba, but in the United States they lost that status. They weren’t “white enough” but they weren’t African American either; so they constituted a kind of intermediate. Cuban children could go to white schools, but the writer Carlos Eire, for example, remembers that when he arrived they told him to go to “the back of the bus.”

Generally speaking, Cubans would face racism in the United States that they had not seen in their native country. At the same time, black Miamians were unhappy with the fact that Cuban refugees could go to white schools and that many were being “taken away from their jobs.” Cuban refugees could also receive more federal assistance than African-American citizens.

Finally, I return to the issue of changes in the Catholic Church in the United States and in Cuba. Catholicism was becoming more popular and widely accepted in the United States (remember John F. Kennedy was the first Catholic president, elected in 1960). Miami had just had its own diocese when Father Walsh arrived in 1958.

With the arrival of thousands of Cuban Catholics, including children, Father Walsh and the new diocese saw an opportunity. As Catholicism rose in the United States, it collapsed in Cuba. Fidel Castro faced the Church, which was still quite Spanish at the time. He could consider the Church as a “vestige of colonialism” that still haunted Cuba. Expelling priests and nuns and closing parochial schools were common events in the new revolutionary reality.

In fact, many Peter Pan parents found out about the program through these closing schools. Also, for my book I interviewed ten Peter Pans and two civil rights leaders, which provide new perspectives.

From your point of view, what is the overall balance left by the OPP?

I believe the parents made the agonizing decision to send their children to protect them. However, things did not turn out as they thought. Most believed that they would be separated for a short period. But many children did not see their parents for years, and some only met one of the two. And there are cases in which the children did not see either of the parents again.

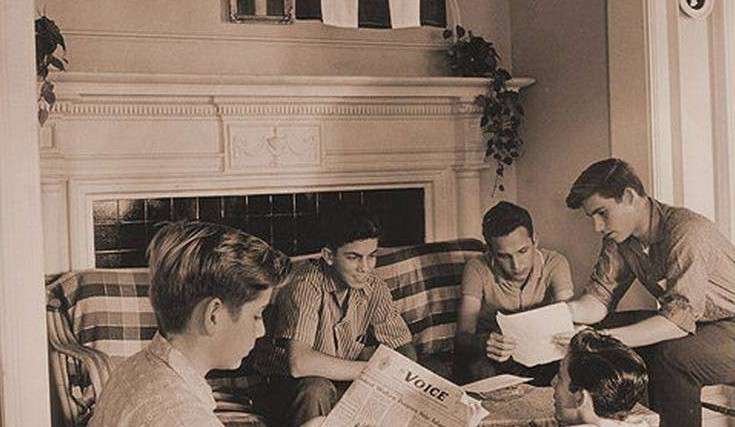

About two-thirds of the Peter Pans needed support when they arrived. They had no friends or immediate family to take them in. For the most part, the parents believed that their children would remain in Miami. I insist, most thought they would meet in a matter of weeks or months. But the Missile Crisis closed the airspace between the two countries and it became very difficult to reunite with the children.

With more refugees arriving each month since 1959, the US government and the state of Florida decided it would be a good idea to relocate the refugees out of state. Children were sent to places like Montana, Washington state, or Iowa. Parents sometimes didn’t know exactly where their children were. The more far-reaching historical turn saw plans unravel, beyond the control of parents, child welfare services and, of course, Peter Pans themselves.

Most of the Peter Pans have favorable impressions of their transition to the United States. But there are also stories of emotional trauma and psychological, physical and sexual abuse. These anecdotes are not often discussed. For the most part, in public there are only stories favorable to the OPP.

How do you see, over time, the role of the Catholic Church in this process? Did she act out of humanitarian patterns or Cold War ideology?

I’ve talked about that before. I think the Church went both ways. Sure, Monsignor Walsh believed it was his divine duty to help the Peter Pans. The Catholic Church had been staunchly anti-communist since the 1930s. Part of the Cold War discourse in America was that the Soviet Union and other communist societies were “without God”. So helping the faithful, Cubans included, was part of the nation’s Christian duty to combat communism. Catholic leaders in Cuba said the Revolution had to choose: Rome or Moscow. He chose Moscow. And the Church of Cuba opted for exile. Although there were Catholic leaders who stayed in Cuba and continued to be anti-Castro.

How would you define the insertion of the Peter Pans in the receiving society, first as children and later as adults?

Well, there was a mix. As I said, because Cuban children were racially viewed as “other” in the United States, they were sometimes considered part of the “refugee problem.” But, above all, the Americans saw in the Cuban children an opportunity to show that the United States and its capitalism were superior to communist societies.

While doing research in the National Archives, I was struck by the number of letters from ordinary Americans who wanted to foster or adopt a Cuban child they had never met. Adoption was prohibited, but interest in the well-being of the Peter Pans suggests that accepting the children and their refugee compatriots would be for a greater good: making them Americans.

As adults, the Peter Pan community in Miami remains a strong political bloc.

One of the topics I deal with in the book is the differences between the Peter Pans who left Miami and those who stayed there. There may be cultural differences, such as feeling more comfortable speaking English; as well as political differences. Some of the Peter Pans I spoke to found the Miami Peter Pans having a hard time exchanging on politics.

They are linked in their experiences and identities, but their paths to Americanization could be different from where they ended up: Montana or Miami, for example.

Why did you decide to dedicate a chapter of the book to the return of the Peter Pan Cuba?

I was very interested in learning when Cubans began to feel like Americans and how they came to inhabit their identity as Cuban Americans.

The issue of returning to Cuba divides the community. Many say they will not return because they would betray their parents’ decision and sacrifice. A Peter Pan told me that returning to Cuba would betray the memory of his father, whom he never saw again, and would complicate his identity as an exile from him.

When one is exiled, another of them told me, they cannot return to the country of origin until the policy that motivated the exile changes. In Cuba it has not happened, broadly speaking.

However, for others, returning to the home in Cuba where they were children can be a healing experience (many use the term “healing”). They feel more Cuban and thus a part of their identity is affirmed. In addition, some of the trauma associated with abandonment is healed.

To what extent have the Peter Pans contributed to creating a Cuban-American identity?

They are part of a larger exile community, but they hold a special place. They were unaccompanied children. Cuban refugees have many stories of hardship and trauma. But children who arrived alone on a plane or boat when they were 6, 7 or 8 years old had to face particular difficulties.

Also, the issue of migrant children is in the news in the United States. Governor Ron DeSantis is following other Republican governors in wanting to politicize the issue of migrants to attack President Biden and the Democrats under the argument of border security. DeSantis authorized the closure of a detention center that housed migrant children. This sparked controversy when the Archbishop of Miami, Thomas Wenski, suggested that helping unaccompanied children today is akin to helping the Peter Pans of the 1960s.

DeSantis then held a press conference with members of the Peter Pan community, who attested that they and their circumstances were different than today and that the comparison should not be made. The political relevance of Peter Pan, particularly in Florida today, remains acute.

Professor John A. Gronbeck-Tedesco will present your book at Books & Books, in Coral Gables, on Friday, April 14 at 6.30 pm