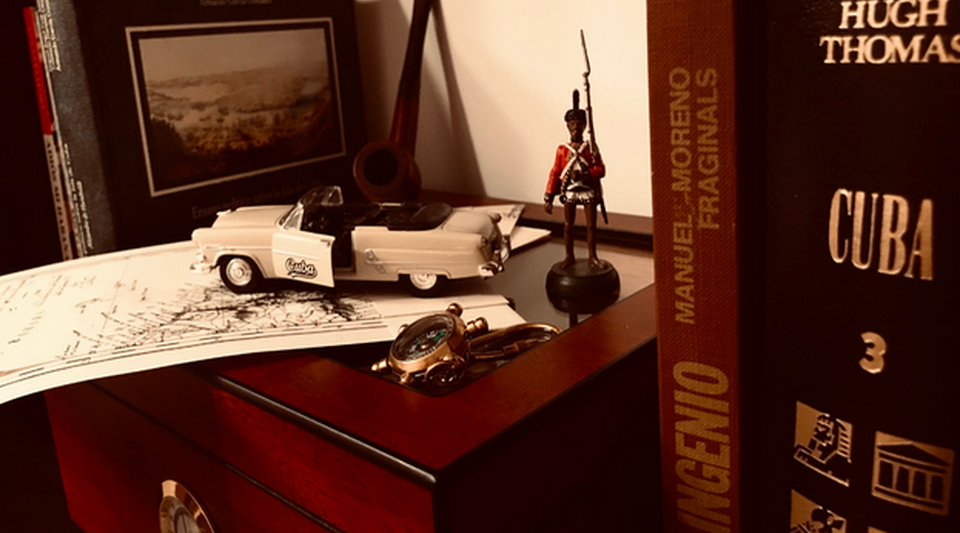

When all is lost, two loyalties remain: memory and language. They both fit in a book. A single volume can contain, at least in a symbolic and potential way, the faces of the people we met, the cities that welcomed us, every object, instrument and clothing we wear, entire smokes of tobacco, the taste of conger eels, maps, sounds and photographs.

Words, in short, that intertwine and dissolve in silence. Lithographs, readings, definitions, in perfect rhythm on paper. That book we call a dictionary –or its monstrous and universal variant, the encyclopedia– occupied a sacred place in every Creole house. Robust, a veteran of many wars against carelessness and dust, the consultation kept him alive and at the top of the bookshelf.

It wasn’t until I knew how to read that my grandmother agreed to let me flip through it. Ours was a hardcover Larousse, and that magic word, retractable, which designated the French publisher that had been printing it since 1855, was for me synonymous with mystery.

Everything was there: hidden in the guards paraded the flags of the world, just as they were in 1960, bothered only by the Swiss and the Vatican – square and not rectangular – and by the double peak of the Nepalese pennant. In the center, on a double page, was the diagram of a formidable aircraft. Pink pages for Latinisms and solid line engravings with crosses and heraldry.

Everything was lodged in my memory so vividly that, if I close my eyes, I can caress the imposing Larousse as if I were holding it in my hands.

If the Island disappeared from the maps, that volume would be enough for me, Martí’s diaries, Lezama’s baroque prose, a colonial recipe book that I keep and one last cigar to recover it

Over time I had other dictionaries, I accumulated and lost books, I worked in libraries and I managed to collect almost all the copies of an Encyclopedia Britannica, with a blue cover and golden letters, as old as the ones that bewitched Borges.

But if there is a book that marks my maturity, in the sense of discovering something legitimate and mine in it, it is the Provincial dictionary (almost reasoned) of Cuban voices, by Esteban Pichardo Tapia. If the Island disappeared from the maps, that volume would be enough for me, Martí’s diaries, Lezama’s baroque prose, a colonial recipe book that I keep and one last cigar to recover it.

I had in my hands, a long time ago, its 1861 edition –the first, of which the Royal Spanish Academy treasured a copy, is from 1836–; the paper was brittle and amber, but the words were so fresh and musical and permanent that we still use them.

Pichardo, a globetrotter who traveled the Island from end to end writing down expressions in his notebooks, taught me how the Cuban language sprang from peninsular Spanish, was refined like rum and matured like guavas.

“Ripe avocado, safe fart,” says the wise man, but not before clarifying that Cubans prefer to sprinkle it with salt and serve it in salads

He collects jokes and phrases that make us laugh in the loneliness of the library. “Ripe avocado, fart for sure,” says the wise man, but not before clarifying that Cubans prefer to sprinkle it with salt and serve it in salads.

In Pichardo, if a man hangs around the kitchen, he is a casserole and the dog that has no hair is Chinese; Camagüeyans “eat everything with their hands” and Dominicans –or Dominicans– “eat shit with their beaks”. Smoking tobacco is headstrong and when they finish ajiaco and the partyany spark cute and of “free life” can diagnose: “neither tó, nor ná, neither chicha nor lemon”.

The natural ones of Remedios are keys and the fishermen of Matanzas, crabbers. The stupid or clumsy is a heatwaveor better, a chirimboand you run the risk that a babujal – chipojo for the Bayamese – it slips down to his stomach through the narrow door.

On the coast there crabs, higuanas Y turtles; on the mountain, carairas Y dye auras, who open their wings “in a cross” when they see the nakedness of their children. The veguero calmly smoke your blunderbuss or, if you don’t have time, spend a little cigar panetela that has been stored in the flaskor safely in your cataurus.

Whoever reads the dictionary – almost reasoned, Pichardo humbly admits, who does not aspire to be encyclopedic – will have a pocket Cuba, a portable and abbreviated island. Every one of the entrances, sayings or jokes of the old Creole is there. Pichardo recovers the old recipes of the midwives from Villarreal and the vocabulary of the sugar mill, such as drum, pan Y graveyardwhich the island’s mischievousness later transformed into love jargon.

Pichardo did not invent our language, but he was the one who first saw it in its entirety, voluptuous, unique, colorful

The book did not enrich Pichardo, who died poor and in pain. Despite also being a geographer and novelist, he has never been appreciated as he deserves. He did not invent our language, but he was the one who first saw it in its entirety, voluptuous, unique, colorful.

He was an enlightened Creole and his dictionary –in this rude, boring and scattered age– offers me pride and confidence in the Cuban tradition. The deep roots of the language I speak, its link with the country that one day we will have to recover, together with the secrets of the tibiri-tabara.

Borges hoped that, when he died, he would be awaited in paradise by “the books I have read under the moon, with the same covers and the same illustrations, perhaps even with the same misprints.” I long for that same hiding place of memory: a quiet room, enclosed by wooden shelves, where the endearing Larousse of my childhood and Pichardo’s dictionary-island coexist.

________________________

Collaborate with our work:

The team of 14ymedio is committed to doing serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time becoming a member of our newspaper. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.