Instead of staying to rest (it was Friday and my body knew it), at three in the afternoon and with Avenida Las Heras overflowing with cars that were rolling in the same direction, staging something like a kind of every man for himself, I took a bus (read: bus) half empty to get to the cemetery of La Chacarita. There were several free seats and I settled into a single one located almost at the back.

The red bus passed the Garibaldi in Plaza Italia and then, turning left, crossed Palermo. The Borges neighborhood, I thought; that of Evaristo Carriego. Carriego lived more or less near the place where the transport passed when “Palermo was carefree poverty” and in the “impatient nights of October they took chairs and people to the sidewalk.” We are in October and I also saw people and chairs on the sidewalk along the way, but arranged in those beautiful extensions that restaurants have in the neighborhood now.

Another phrase by Borges is that the vindication of the antiquity of Palermo was due to Paul Groussac, one of the three blind writers that the Argentine National Library has had (two is a coincidence, three a confirmation —Borges again) and whose pantheon forms part of an imaginary walk that the museologist María Elena Tuma, who works at the cemetery’s Historical Heritage Center, has not been able to achieve due to lack of funds.

In La Chacharita I asked for a place to locate certain burials and a custodian pointed me to the end of the building. Immediately he was knocking on a door through whose windows tables and dozens of books with thick spines could be seen, under which the names of deceased people sat. At the moment a woman opened it, she would say almost by chance. It was Maria Elena Tuma. After the greetings, I asked her for the name that had brought me there on such a peculiar journey: the writer Héctor Libertella.

It turns out that a few days before, a friend who lives in Texas had asked me to photograph the tomb of Libertella, a writer that I was completely ignorant of. I am not ashamed, if at the end quite distant from Socrates that I am. After telling me that he had been unsuccessfully searching for Libertella’s tomb on Google Maps, this friend tells me: “Read The architecture of the ghost. It’s worth it”. And when I started to track down the book, or any other, at least I found that Libertella had been, in addition to a writer with prizes awarded by the magazine Front page and the publisher paidosCONICET researcher, editor and that his death occurred when he was 61 years old, on October 7, 2006.

“What a coincidence!” I said to María Elena Tuma, because after having told her that in this one I would look like Mariana Enríquez, whose book I had just read someone walks on your gravetold me that just at that moment they were putting on one of the underground catacombs a work by the writer, No meat on us. Repeated coincidences because October marks the death anniversary of José Ingenieros and Evaristo Carriego, both buried in this place that owes its existence to a yellow fever epidemic.

Tuma was in front of a computer monitor. I listened to each explanation and observed the place: the stacks of books, the tired light that continued to enter through the windows, the tall prop of the building, the books she had on the table; one by Osvaldo Soriano, another by Cees Nooteboom. In that I hear that she laments: “I don’t have where Libertella’s remains went.”

Oh no, I thought. The remains of the writer were no longer on the ground. He explained to me that after four years they stop staying in a tomb, although their stay can last between eight and ten years, when what is called a “cleaning” is done, the result of which is cremation. The ashes are of “free transit” and those exhumed and unclaimed remains, due to inability to pay or whatever, go to a general ossuary, which means that the name of the deceased disappears. After a while, María Elena Tuma said: “Here is Libertella.”

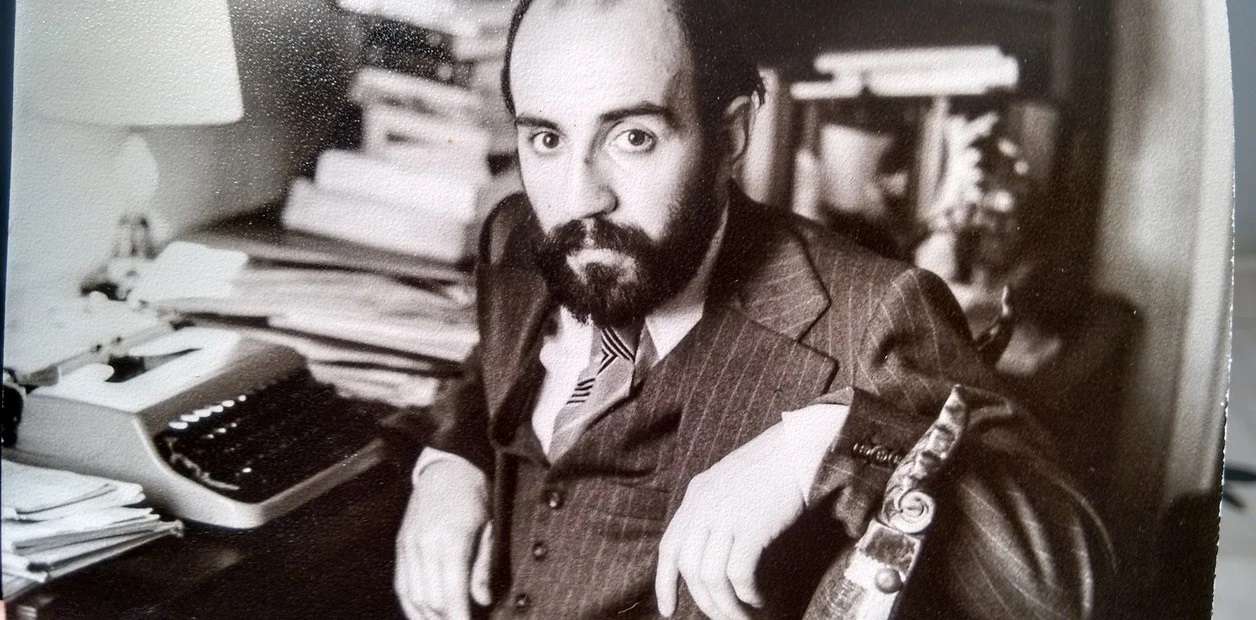

The day before, he had visited the Varela Varelita bar for the first time, a place that, because it was close to his former apartment, was frequented by the writer of other works such as The path of the hyperboreanshis first novel, or The legend of Jorge Bonino, the last. There you can see a portrait of him on a column. They say that he used to sit at the next table. Libertella, with mustache and beard, wearing glasses, types with her forefingers a typewriter. She looks older than she should have been.

On my second visit to the place, I talked with Ramón, who as a waiter often attended the writer when he arrived, so many times, they say, accompanied by his friend, also a writer Ricardo Strafacce. “The writer who won a lawsuit against María Kodama”, is how Google presents him to me and I hope to meet him in person to talk about these issues. Until that moment arrives, I follow this chronicle.

Varela Varelita is one of the notable café-bars in the city. Tables and chairs outside. From the stop that is in front and thanks to the glass you can see the diners. Women or men, alone or in groups, various readers. Neighborhood atmosphere, full to the brim around noon. As I talk with Ramón, a woman raises her voice to ask if someone can lend her a cell phone, she says so loudly that we can all hear. “To read something for a little while,” she adds. One of the waiters answers from the bar: “bring it here”. The lady replies that she must read at the table and continues to ask in a tone powerful enough to overpower the staff if someone then lends her a charger. She is accompanied by an elderly woman who is sitting in a wheelchair.

“Here in the basement there was a box of Negrita rum, we discovered it one day and over time he drank it all,” Ramón tells me, who must have been very young when Libertella came to this place located on the corner of Scalabrini Ortiz. and Paraguay. “One day the husband dies and doesn’t pay the rent,” he says now and in the same tone as before, the woman who asked for the charger.

When Ramón leaves, I take the opportunity to drink a beer and read a book by a Cuban writer and friend. The closure is the story about a meeting between a writer from the province who is part of an official mission thanks to which he has left the country, propitiating the reunion with an emigrated friend. The tone is melancholic, sad, inevitable. “The life of Favarolo”. The woman has interfered with his voice again. Follow the reading from the phone: “He created a care center in his town.” “A center? asks the old woman whom she accompanies. “A care center”, answers the lady, who will be close to sixty and has very well-groomed hair and is well dressed. “It was rotten with corruption,” she blurts out now: “That’s the word. He was rotten with corruption.”

The friend who had left me the commission to make a portrait of the site where the remains of Héctor Libertella are found has read stubbornly, and with the authors (perhaps now he is deeply impressed with the authors) from Argentina he seems more impressed than before, when in the city of Holguín he lent me books that I did not know or had been unable to read. He comes up with those kinds of ideas, which is why I pray that from now on he doesn’t want evidence of the house where Hebe Uhart was born, or of Sergio Chejfec’s elementary school, perhaps of the penultimate apartment in which Piglia lived or of the hospital where Edgardo Dobry gave the first cry.

The ashes of Héctor Libertella are found in the twelfth gallery of the La Chacarita cemetery. On that side you come to the mausoleum of Carlos Gardel and the tombs of the writers Soriano and Groussac. You have to turn left and go down some wide marble stairs to access an underground, circular and naturally lit gallery. In the center, among the greenery, I see a reproduction of La Piedad. The walls are covered with niches, some of them identified. Some niches also have flowers. “I’m sorry I didn’t bring one,” I say to María Elena Tuma, who kindly guided me there three minutes before the cemetery gates closed at five. “For the theft of the bronze”, she tells me.

I will repeat the visit, surely this Friday or the other to see the play about the stories of Mariana Enríquez before they stop playing it. Then, having perhaps read one of the books, my flower will arrive for Libertella.