Cannons and rifles thundered. Behind any ceiba or carob tree an insurgent could appear with his fearsome machete or a cane-devouring torch. The war had to be ended at all costs to preserve lives and property, thought the high command of the Spanish army.

Then came the plan to build a system of fortifications in the central region, from the Júcaro pier to Morón, in order to prevent the invasion of the West by the liberators. The idea was conceived by Francisco González Arenas, a weapons master, mechanic and owner of a farm in the region.

By order of Captain General Blas Villate de la Hera, Count of Valmaseda, construction of La Trocha began in 1871, and in 1874 it was still being perfected. It had 33 wooden forts, with an earthen breastwork, a moat, barbed wire, palisades, ditches, a telegraph line, camps, and a section of railway. But one thing is the theory and another very different, sometimes, the practice: the insurgents passed from one place to another, guided by peasants from the locality.

Upon verifying the ineffectiveness of the Trocha, there was discontent among the officers and they began to imagine alternatives. One of them was to open a maritime channel that would be traversed by well-armed boats and each bridge would be protected by a strong detachment. In addition, the work would contribute to economic development. This is how its enthusiastic promoter, the artillery captain Francisco Cerón, in an article he authored published in The Military Echo and reproduced by Navy Journalon March 23, 1889:

The veteran who fought on the plains of Camagüey said:

(…) once the campaign was over, it would have been a comfortable route and natural outlet for products from the areas on both shores that are so lacking in communications. But if it does not exist, it should occur (sic) if it would be convenient to open it if a propitious occasion arises.

He raised the need to carry out a feasibility study to find out if it was difficult to create an anchorage in Júcaro, to the south, for the ships that would cross the new route and if in Morón, in the closed space in the area of Turiguanó and the Coco and Roman, a port could be opened.

The existence of a railway, inaugurated in January 1880, from Júcaro to Morón and passing through the town of Ciego de Ávila was an aspect in favor of the project. Cerón considered that the railway line should reach Remedios from the north. Between Sancti Spíritus and Puerto Príncipe there was a demarcation rich in cattle and wood.

In addition, the commentator thought, the canal would stimulate the cultivation of tobacco and sugar cane in the virgin lands of that region. He knew that region well because he traveled through it during the Ten Years’ War and confessed in 1895 that it was at that time that he first thought about the military utility of the canal.

He also considered that the canal would shorten the navigation time to Havana from places located between Cabo Cruz and Cienfuegos. In order to finance the work, since the State did not have the resources, he proposed that the possibility of establishing a company be analyzed.

Ceron insists

Cuba had been shaken by war since February 24, 1895. Then Cerón went back to The Military Echo in search of support for his old proposal. Among other arguments, he expressed in a letter dated March 12, 1895:

The necessary works, in our opinion, are not of relative importance, the flat terrain rises little above sea level, and it seems that it lends itself to excavation work. We cannot set at this moment the estimate that we approximately formed then, calculating the cubic meters that had to be extracted to the west from similar works in Panama, but of course, we believe that the total amounted to one million and a half or two million gold pesos. We will notice that, since there is a railway line along its entire length, work is greatly facilitated, and given these conditions, it is to be assumed that by offering certain advantages and privileges such as those granted to the railways, there would be a private company that would undertake such work. important as patriotic.

I imagine Cerón’s state of mind when he learned details of the reconstruction of the Trocha, in 1897, by order of Valeriano Weyler, and found that they discarded his project. There was talk, in that year, of a canal in Nicaragua, similar to the Panamanian one and this anguished the Artillery Captain even more.

transcuban

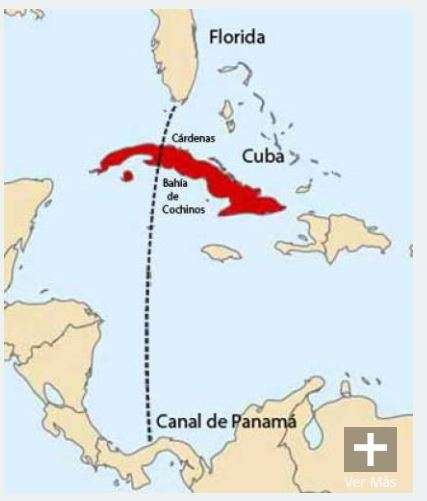

The idea of building the waterway returned to the public arena on July 1, 1906, when the journalist Francisco Carrera Jústiz, in his municipal magazine, defended the importance of a channel. He proposed that it be erected between the Ciénaga de Zapata and the Bay of Cárdenas to alleviate flooding in the Colón area and at the same time boost the country’s economy. Since the previous month, the Government of Tomás Estrada Palma had contacted the Cuban engineer Aniceto G. Menocal, based in New York and who was commissioned by the United States government to conduct studies of a possible canal, both in Panama and in Nicaragua.

The renowned specialist traveled to Cuba and was in charge of preparing the project. The so-called Roque channel, 50 km long, Between the Carrara Lagoon, in Colón, and the Cárdenas Bay, it would cost half a million pesos and would take three years to complete, according to the engineer’s calculations. But the law that would approve the budget “slept” in the Senate until 1910. This canal was made with excavators used in Panama and the United States, although it never became navigable as desired journalist Francisco Carrera Justiz.

In 1912 a transport structure that connected New York with Havana. The journey, by rail, began in the big city and arrived at Key West, where the wagons were transported by boats to the Cuban capital. This new communication route revived the project to build the maritime canal in Matanzas.

raised controversy among The worldwhich he opposed considering that it would affect the territorial unity of the nation, and the Navy Journal, defender of the initiative, since he valued as very positive the influence that it would have for the promotion of agriculture, tourism, commerce and the settlement of uninhabited places.

He Navy Journal assured, in the edition of April 13, 1912, that the idea of opening a trans-Cuban canal was very old and had among its promoters Francisco de Arango y Parreño, Antonio del Valle y Hernández, the engineers Francisco and Félix de Lemaur, Franscisco Javier Cisneros and Federico Argüelles y Quiñones.

Júcaro and Morón in the peephole again

Enrique Pérez Cisneros, Cuban ambassador in Chile, wrote a report to the Secretary of State, published in the Navy Journalon January 29, 1915, which read:

The line between New York and Panama would be almost straight with increased savings in time and expense for navigation. Now that Cuba is about to enjoy an era of permanent peace, the old obstacles to its complex development lose their raison d’être and the channeling from Júcaro to Morón is a simple act of getting down to work with good will (…)

This new pipeline does not present engineering problems. The terrain is flat and the extension is about four fifths of the hymn of Panama or less. The rise that the magnificent ones of that region will experience will begin widely, it will amply compensate Cuba for the expenses that the canalization may incur, not to mention that the town abounds in excellent materials necessary for this kind of works, especially in terms of hydraulic lime or cement.

Via Cuba

Pérez Cisneros’s proposal was shelved. Years passed and it seemed that no one was going to think of a similar plan until the idea of Canal Vía Cuba arose. This time it was close to materializing, since the government of the dictator Fulgencio Batista gave it the go-ahead.

The American company “Compañía del Canal del Atlántico al Mar Caribe”, by Decree No. 3652 of December 6, 1954, won the concession to build the work that would cost 400 million dollars. This company would have the right to operate the canal and its facilities for 99 years.

Since the Congress of the Republic was suspended, the Decree was considered illegal, and caused a national scandal, as sectors of civil society strongly opposed it through political acts and newspaper articles, written by notable intellectuals such as Jorge Mañach and Oscar Pino. Santos, because they considered that it would affect the sovereignty of the country to build that road between the Bay of Cárdenas, on the north coast, to the Via de Cochinos, on the south coast.

The influential politician Orestes Ferrara called it a gigantic scam. The students, led by José Antonio Echeverría, played an important role in the campaign. The popular pressure was so great that, once again, it became a chimera to have a canal like the one in Panama.

Sources:

Bohemia

Navy Journal

Granma

rebel youth

Ernesto Alvarez Blanco: Going up the stairs like a sun. Biography of José Antonio EcheverríaEditorial Casa Editora Abril, City of Havana, Cuba 2009.