Raploch, 2012. That year, this district of the city of Stirling, in Scotland, hosted an unusual concert in which children from the area participated, together with the famous “Simón Bolívar” Youth Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela. It was part of an experiment to see the impact that immersive music education could have in a community with high levels of social exclusion. Ten years later, what has become of those children?

But before seeing what the results of the test were, it is important to explain that Raploch does not have a good reputation. In English dictionaries the name of the area also appears as a pejorative adjective to describe “ordinary, plain, undistinguished people; coarse, rude.”

The neighborhood, full of gray houses built by successive British governments for low-income people, is located at the foot of one of the main tourist attractions in Scotland: Stirling Castle. Nevertheless, unemployment, poverty and crime have stigmatized him.

However, something has changed in these years.

Making noise

Three decades ago, only one child from Raploch played a musical instrument. Today, that number exceeds 400 and the Scottish quarter has its own symphony orchestra.

The 2012 concert seems to be the reason. At the recital, a group of Scottish children, who were part of the then innovative program called Big Noise, joined the Simón Bolívar Youth Group, which was then directed by the Venezuelan director Gustavo Dudamel.

The performance on a damp, gray field near Raploch was watched by a cheering crowd swathed in waterproof ponchos.

A decade later, the taste for music has only grown. Two of the boys who played at the concert, Solomon and Dylan, are now regular members of the band. Raploch Symphony Orchestra.

For her part, trombonist Symone Hutchison, now 20, is about to enter her third year at the Royal Conservatory of Scotland.

“I didn’t really understand how big it was,” she said, “but I was very excited, seeing Gustavo and seeing the Simón Bolívar orchestra play was incredible. She was totally inspired ».

Luke Barjoti, who was 12 years old at the time, took a bow on stage and today, 10 years later, he has just finished his music degree.

How do you remember that moment? What did it mean for his life?

“I would say he had a huge and significant role,” he replied.

“It was an experience I will never forget. Before Big Noise I didn’t know cellos, violins… it never crossed my mind. Neither my mother nor my father, nor any member of my family ever learned to play an instrument.

Following the Venezuelan example

The Big Noise program began in Raploch in 2008 and was the first in a series of projects, inspired by the National System of Youth and Children’s Orchestras and Choirs of Venezuela, which Scotland launched.

El Sistema is an initiative that seeks to combat social exclusion and reduce crime in the poorest neighborhoods of Venezuela, through the teaching of music.

The project promoted by the late teacher José Antonio Abreu was born in 1975. The economist and musician, who became a minister, managed throughout his life that the different Venezuelan governments, regardless of their color or ideology, financed the initiative that today is known worldwide.

In their 45 years of existenceThousands of children and young people have passed through the System and renowned musicians and orchestra directors have emerged, one of the most famous being Gustavo Dudamel, who conducted that famous concert in 2012.

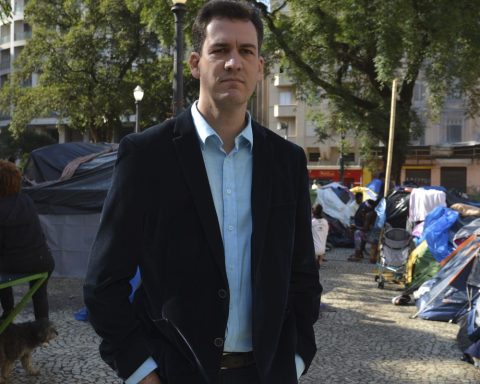

The BBC He spoke with Dudamel in Barcelona, where he is preparing a series of concerts, and was shown what had happened to the children he met a decade ago.

“Wow,” he said smiling as he watched video messages from some of his former students. «This is what the system is. I remember it as one of the most special moments of my life (…) that beautiful meeting with all the children, with all their families with the community was a really very special and unique moment».

Dudamel highlighted the power of social transformation that music has. «What is poverty? We think that it is about something material, that it is the lack of money or possibilities, but the worst thing about being poor is being nobody, nobody in society. Being excluded is the worst », he stated.

He held himself up as an example of how inclusive art is. «I am Venezuelan, but when I play Beethoven or Mozart or Elgar or Stravinsky, I feel as if they were part of my DNA, of my identity, because it is universal».

part of the landscape

Back in Raploch, it’s clear that The Big Noise’s office has become part of everyday life.

While a boy named Luke was being interviewed, two other girls came by on bicycles to see what is being done there and what could be offered to them.

The girls were not impressed. The reason? One plays the violin and the other the cello. This proves what has been achieved in a decade, it is no longer surprising that young people know how to play an instrument.

That same night a symphony orchestra concert in a church, Ben Morrison, an 18-year-old tuba player, celebrated his graduation, after spending 11 years as part of The Big Noise project.

The celebration, however, has a bitter taste. “I love every minute”, said. “I love all music. Unfortunately, I have already reached my age, I hope to be able to return as an assistant ».

“I’m proud of where I come from and I’m proud of what I do,” he added.

The Big Noise has not solved all of Raploch’s problems, but if 15 years ago this neighborhood was known for its problems, today it is for its music.