My name is Nadia, but for my mom I am Nobody. She doesn’t see me, and I hardly see her. Sometimes, when I feel Thunder’s motorcycle coming to drop her off, I run out to kiss her and tell her how things went at the store, but she pushes me away with her hand and bumps into the bed. Half the time she doesn’t take a bath or eat.

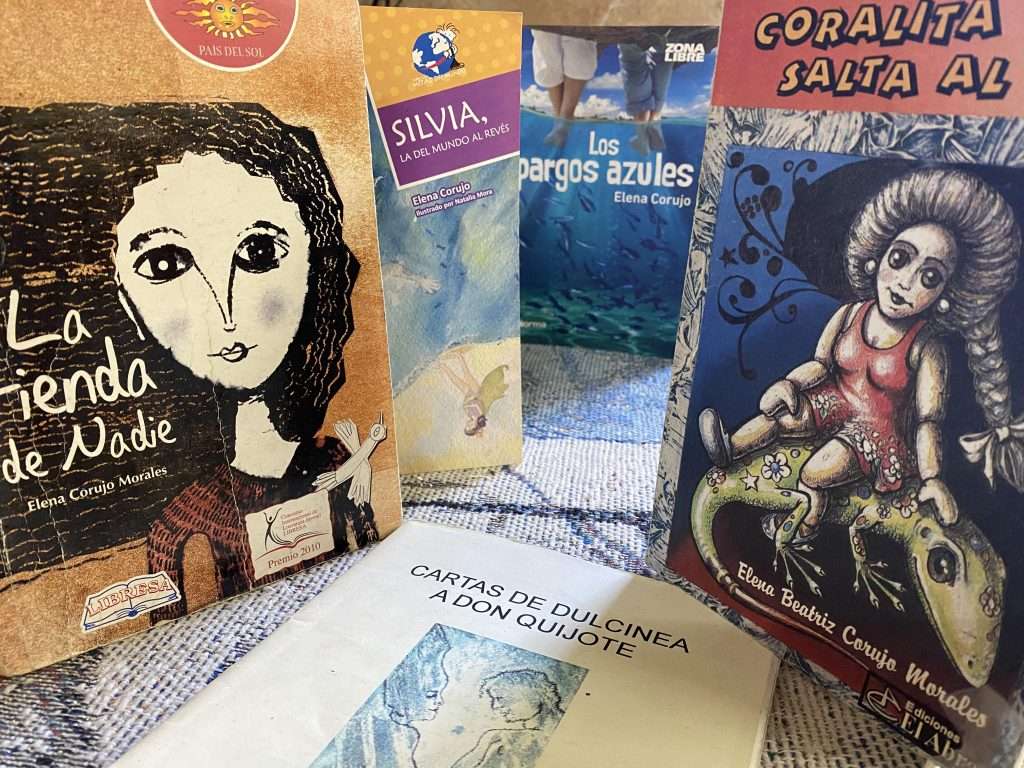

so it begins Nobody’s shop, a novel that tells of the abandonment of a 12-year-old girl who lives with an alcoholic mother and without contact with her father, who emigrated to the US Elena Corujo wrote it almost 15 years ago. It was not her first work, but it was her first Grand Prize in cash. Thanks to him, the former Spanish and literature teacher in high school, and later a TV director in a telecentre, she was able to “raise her head”.

Her sister publicly recalled about three months ago, upon receiving on her behalf, in Valladolid, Spain, another Prize, the Laguna de Duero Poetry Prize, that as a child Elena did not write, she simply spent hours on the floor of the parlor drawing human figures, to whom he then constructed oral histories and spoke to them.

The Corujos, all three of them, since there is also a brother, had a happy childhood in Remedios, in the center of Cuba, immersed in what Elena herself calls “village wealth”, which is sometimes difficult to describe, but which understands unusual events, strange characters, indecipherable names, mysterious pasts, betrayals and fidelities… Although his stories take place in the present in which they are written, they are permeated by those experiences of previous decades.

“I knew all the neighbors. When the light went out we played to trace the psychology of the characters in the neighborhood. My dad told me: ‘Who is Cress?’ He is the crazy man of the town and he acts in such a way… ‘Who is Trovadio?’ He is the winemaker and he does such a thing… I am the daughter of humble people from the town, but my father recited Lorca and León Felipe and my mother listened to soap operas on the radio, she read a lot and adored Rubén Darío.”

“I was a very restless girl, but I have never been agile, I always fell into any mischief. I read and I got into playing characters. Once I thought I was Juana la loca and I took my brother, I put him in a drawer and I went to the park saying that it was Felipe el Hermoso. She dreamed of being an actress, not of writing. When I was 16, I took the exams for the National School of Art and I passed Acting and Painting, but my dad didn’t let me come to Havana.”

At the age of 3, Elena Corujo learned to read because there was a teacher who reviewed the children in the next house and she listened to her from her own. But that was 60 years ago in Remedios. Now what she hears are shouts, arguments, swear words, reggaeton… That without even having to leave what she calls her celtic Cave, where he lives 5 years ago. A wet room that in just 4 square meters brings together a kitchen, bathroom and living room, which she acquired thanks to a literary prize. Ah, but it is located a stone’s throw from Avenida 51, in Marianao, and where those same scandalous neighbors help you get what little you can get in the devoid of nearby commercial establishments.

“Here I have written less, and I do it listening to those cries of the people of the neighborhood at all hours, but they nourish me, because some of the things they say make me laugh and also because I can feel their lives or rather their survivals, which They wear them very strong, ‘pretty’ for their children. I also saw it on the Isle of Youth, but those were different times. There I had a wonderful landscape, from my apartment in the Abel Santamaría neighborhood I could see the sea if I stood on the balcony and the mountains if I stood on the patio. I got to know the entire island. That’s where I wrote the most.”

Elena arrived in Nueva Gerona in the 1980s with her son. She left behind teaching and, to some extent, her roots. But she had begun to write. And soon after, she started chasing contests and prizes. “When my son was born, I was 22 years old and I started doing poetry. I won the Villa Clara Prize in 1984, which was for children’s poetry, but that was not published.”

His first published book was doodles and pigeons, also of poetry for children, a volume that saw the light because it won the 1987 “Red Mangrove” Contest, on the Isle of Youth. From then on, his Smith Corona machine was not going to stop until well into the 2000s, when he was able to have his first computer.

Written in one go, as all his books usually are, his first narrative pieces came out of that Pentium 1 PC, slow and complaining. It all started with dear coralitaan epistolary novel, in 2001. They are letters from a girl named Emilia to her best friend who has left the country, to whom she tells wonders and anguish of her adolescent life. Coralita jumps to the pon, the second part, will be the answers, also wonderful and distressing, from Coralita to Emilia from Spain. They will see the light thanks to the humble territorial editorial the open. Two sad little books that visually do not conquer any child, although their reading is luminous.

With access to the Internet, things are going to change for Elena Corujo: so many hours to create stories as to navigate in the depths of the network of networks that offers countless literary contests, sometimes well paid. In 2007 she won the Desiderio Macía Silva International Prize, from Mexico, with the book of poetry for adults With irreparable gesture and is published in that country. That same year, a Spanish magazine mentions his short story Letter from Dulcinea to Don Quixote. And in 2010 with nobody’s shop wins the Librosa Youth Literature Award, from Ecuador, a highly prestigious contest in the southern cone.

“Then I wrote blue snappers, which in 2012 won a Mention at Casa de las Américas. Since I saw that no one was interested in publishing that novel, I sent it to the “Norma” contest in Colombia. I was one of the finalists and they didn’t give me the award because I declared that it had been a Casa mention, but they published it in that editorial, which is very important. And then they included it as complementary reading in ninth grade, in Colombia.”

Colombian children are reading the story of a Cuban teenager who is a victim of social exclusion. Daniel is harassed by his grandmother so that he does not relate to his father gay and suffer bullying at school. The snappers… Y The store… They have been marketed in several Latin American countries. Every three months Elena receives sales reports and holds exchanges with book promoters in Colombia. Those novels have done very well.

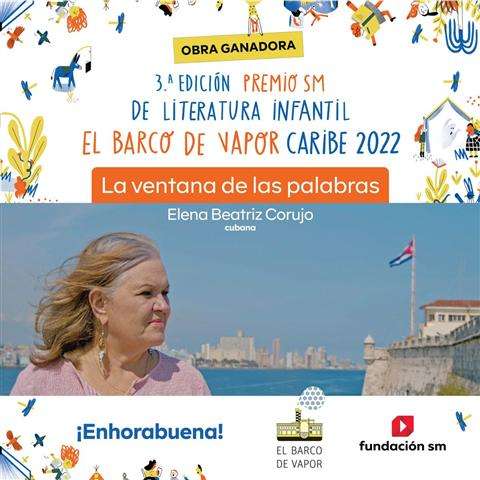

But none of Elena Corujo’s books are part of the catalogs of the most important Cuban publishers of children’s and youth literature. In her Facebook profile recently, she also complained that they did not call her to be part of the International Book Fair of Cuba, which has an extensive program in her children’s pavilions. We would have to see what will happen from now on, after winning with another novel, The window of words the Barco de Vapor del Caribe Award 2022, one of the most important competitions in children’s and youth literature in Spanish.

“I felt sorry, and still does, to arrive with a book of mine to a publisher. And since no one cares to ask me, I send it to contests. It is the way I have had to publish and in a certain way it is my livelihood. Everything I’ve posted is because it went to a contest. I am very competitive, as a child I was. In those street plans or wherever there was a competition, we always went and won, me drawing and my sister running. And we got the best prizes, which were usually toys or cake. People said: here come the Corujo, there is nothing for anyone. Perhaps that explains why I’m not afraid of literature contests and they’re almost always anonymous. I have not had the luck of others because nobody calls me. Also, I’m nice and cheerful, but lonely. Maybe that’s why they didn’t take me into account. I am not a woman of events, nor of literary meetings. I have good writer friends, but isolated, and when several get together, I don’t like to be.”

Elena has never returned to the Isle of Youth and from Marianao to El Cano she has traced a trail. Her grandchildren, a future flutist and a storyteller par excellence, live in that hidden little town in Havana, in a house over 100 years old, ideal for rehearsing and fantasizing. They are also happy children. Not so the protagonist of the author’s recently awarded book, again a teenager, who lives precisely in El Cano. Her father is a schizophrenic painter and her mother a religious fanatic. The grandmother is the breadwinner of the battered family and sells homemade food. Davina has an obsession with winning a Guinness record and that purpose leads her to carry out a thousand adventures.

The characters created by Corujo are victims of family or social abuse or live in extreme situations. In The boy of the proclamation (Mention in the April 2018 Award) the protagonist suffers from Becker Muscular Dystrophy and his counterpart is another mentally retarded child who sells air freshener on the streets. Silvia, the world upside down, (Finalist in the 2017 Libresa contest) is, shall we say, more noble. It tells the story of two twin sisters who face the divorce of their parents, with the aggravating circumstance that one of them has XP Syndrome, a hereditary condition characterized by extreme sensitivity to the sun, which is why she makes her life at night, and the other in the days

“I don’t write about happy children, although they are in a way, but they find happiness through alternatives. The pain of seeing children suffer kills me. In my novels there are happy events, I don’t go only to sadness, there is a lot of humor and, of course, they are very Cuban, but understandable, because the realities that I tell are universal. I do not intend to transmit values or teach. Endings aren’t catastrophic because they’re for kids, and they don’t forgive that, so I try to make my endings happy.”

The most recent Prize won by this Cuban author could change the course of her life: get out of the cave she lives in, have a better computer, travel, emigrate, stop smoking, improve her health, which is severely affected by insulin-induced diabetes. dependent… He has not decided which of these variants to undertake. What she does know is that this new triumph has given her self-confidence. “I never believe that I can get to where I am.” Perhaps Elena Corujo needs a bit of courage from one of her literary creatures, the one she says near the end of a novel: I go with my head held high and looking at everyone who tries to laugh or yell at us. I go with my pockets full of the moons that I didn’t collect, to throw them at the first one who dares to yell at my father…