“The end of artistic activity is not the work but freedom.”

Octavio Paz

It was not a surprise that in the second half of the 1990s, an artist burst onto the scene of Cuban visual arts with a totally unique and challenging work. I say this, because that was a moment that represented a kind of state of grace in Cuban art, continued in the first years of this century and millennium; a period in which various poetics came to light, while others confirmed his probity.

Many new values emerged during that stage when the presence of the market, the most recent guest at the insular art invitation, began to do its thing. Nadal Antelmo Vizcaíno, better known as Nadalito, put up an irreverent face to everyone and everything, quickly placing himself in the critical spotlight. His was a flashing apparition. It was different, which is beyond any discussion, at least for whoever writes this; and as such it established itself in the attention of scholars and followers of our art.

But if it was not a surprise that an artist like him emerged at that stage, lavish in new talents that populated the country’s artistic scene, the way in which Nadal did it was, since he was discovered abruptly with a work in which he They combined their own aesthetic expression, symbolic strength, originality and an eroticism that left no one indifferent.

Nadalito (Cárdenas, June 2, 1968) is a creator who did not come from the training of art schools, but from engineering, which, like any technical career, prepares the individual more to seek solutions to specific problems that to express their abstract ideas through visual forms. In art he was self-taught, which gave him, at the time of his irruption, greater interest in the Matanzas and later national cultural field. But that origin also guaranteed her a greater freedom of choice regarding the themes of his works and the ways of approaching them.

He became known with the series the basketin which he managed, due to the effect of the perspective and the angle adopted, that the sun in its sunset seems to be entering a basketball basket (basketball) as if it were a cosmic basket from the popular game.

A renowned photographer from Matanzas, Ramón Pacheco, accidentally saw the images and rescued for Cuban photography a talent that could very well have been lost in the corrosive daily life of Varadero beach. Pacheco sent the images to a provincial photography salon, and they were declared finalists by the jury. The following year, Nadalito was seen for the first time inside a gallery observing the fruit of his curiosity. That was the beginning.

Other photographs and series of images followed, including erotic story, which recreates a repressed sexual fantasy towards a work colleague. In addition to the good images achieved, this series has the merit of initiating what would henceforth be one of its strongest themes: visual eroticism, which Cuban photography was in such great need of. The series won a provincial hall, while awakening an area of the artist’s brain that had only conceived, until then, the erotic as the common morbidity of the male predator. From the intense libido to the visual representation of that feeling, was the parable followed regarding this topic.

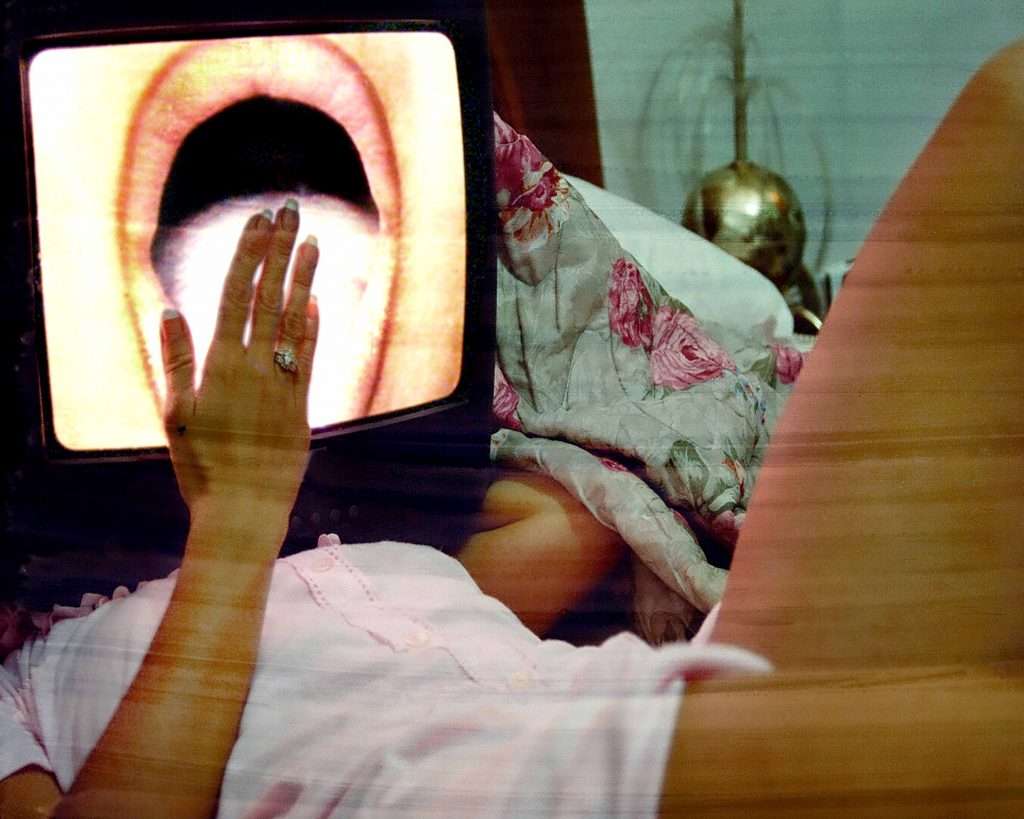

The erotic was one of the organically inherent substances in his initial visual proposal. Stark and visceral eroticism. In 2004 she produced the series TV Playa group of images in which the sexual parts of the body played within a television screen, openly teasing the viewer.

Also in that year he created the series the voyeurthe representation of a foreshortened look from the eyes of a voyeur that observes the thighs and genitals of women who walk over their privileged position, another work in search of a very singular eroticism.

My catalog book The seduction of the look. Body photography in Cuba (1840-2013), Polymita editions, 2014, contains photographs of the body and the eroticism of some ninety Cuban photographers from the beginning of photography on the Island to the date of publication of the volume. The name of Nadal Antelmo Vizcaíno figured from the beginning, his work had to integrate, by its own right, that compilation. The provocative and carefree spirit of the terrible kid of Cuban photography could not be missing. For him, the erotic was in his essence, indissolubly incorporated, it was like his most natural way of being. Pure and hard eroticism, without more.

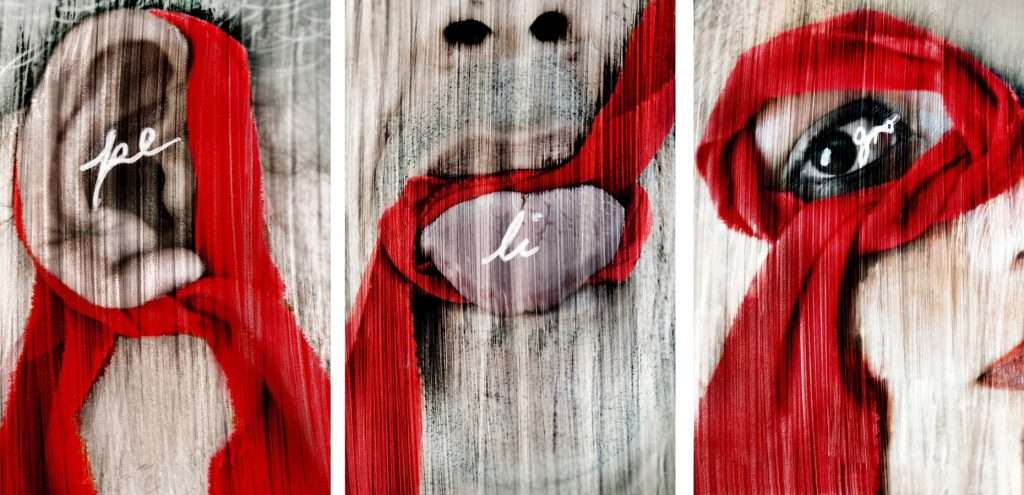

That initial five-year century and millennium was intensely used by the artist to make photographs and series in considerable quantities. Recognition of him grew exponentially. From there were born their syllables, in 2003, which both the artist himself and specialized critics consider to be among his best series. For Nadalito it was an attempt to philosophize with the constructed images, it was like “letting out my deep social sensitivity”, as he put it.

In his work, the image comes from the word as the foundation of the creative process. His method does not consist of using the text as one more accessory, but rather that the idea of the work emerges from it and transmutes it into a symbolic experience, then the word acquires a connotation other inside the image. His work became more dense sociologically and went on to swell what Cuban art had already been doing for some time, generating critical thinking from visuality.

In 2007 he began to put together his project confidence networks and from there he continued for another idea about a hundred photographs that he selected from the previous series and that constituted the beginning of a new project: The hundred Cuban family portraitssociological and ethnological study of our population that only had a precedent in the series This is how we Cubans areby Roberto Salas, from 2007. Sweet Junk, Matters of State Y The hunt for successwere other series in those years until reaching the digital project The liar, made between 2009 and 2011, in which he casually played with the concept of art and proposed some of his most original ideas. That creative effervescence had a substantial moment with the installation wormswhich gave critics much to talk about and evidenced their concern and critical position in the face of cardinal social problems.

In 2015, as a finishing touch to this entire career, Nadalito built his sculpture YES, exhibited in a privileged place at the Havana Biennial. It was the consolidation of his immersion in the so-called contemporary art, to which he had arrived from photography, but to which he now contributed installations and three-dimensional works. A maturity acquired from the experimental that did not go unnoticed by scholars of the country’s art scene.

Nadalito settled in the United States in 2014 and since then has moved freely between that country, Spain and Cuba. Between 2016 and 2021 he produced a group of exhibitions in different international spaces, mainly in the United States, and was five years of artistic silence in terms of new creations. He broke his silence in 2021 with the series of black and white photos Walking Cubanot exhibited in any gallery so far and that caused me to undertake this account.

Renowned authors such as Nelson Herrera Ysla, Magalys Espinosa, David Mateo, Dannys Montes de Oca, Rufino del Valle and Andrés Abreu, among others, have recognized Nadalito’s value and contribution to island photography. I hardly need to underline that it is a general acknowledgment by critics, in particular of authors with many hours of flight in the analysis of contemporary Cuban art and, in particular, on photography. This consensus has been maintained up to the present and is its greatest legitimation.

The imagery created by Nadalito is complex, rich, controversial, postmodern in nature, with a dose of irony, high visual and aesthetic values. He has effectively recreated prevailing sentiments in Cuban society, such as desire and lubricity, fear of the future, existential doubts, rootlessness in the face of precarious reality, and others. That is the true strength of it as an art.