By EVARISTO MARIN

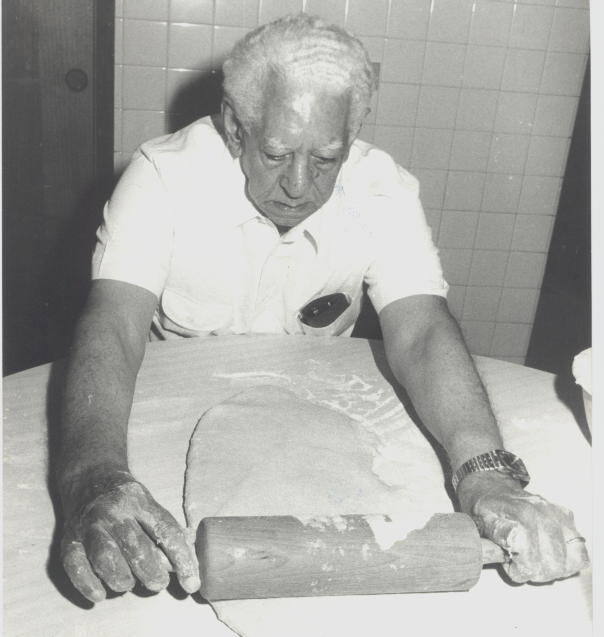

As well as an illustrious educator, controversial politician, insightful lawyer and exquisite poet, Luis Beltrán Prieto Figueroa also had a great predilection for the baker’s trade. “Making bread was very ancient in my family. I trained a lot in that, in my boyhood days”, he expressed himself, delighted, in his old age. His mother, Fita Figueroa, was one of the most notable and admired bakers of La Asunción in the 20th century. In the Prieto family, the tradition of milk bread and seasoned bread, the covered thread, the Tunja bread, the Saboiano, the coscorrón, etc. still persists.

Much is said about the unique flavor of authentic margariteño bread and little is known. It is something that has been in the insular gastronomic taste since ancient times. The singular secret that surrounds its elaboration is also proverbial . Ask in La Asunción. Nobody will give you the recipe to make that famous and tasty bread. Be content to enjoy it on your palate.

Beyond his forceful condition as a free thinker, not at all devoted to religious beliefs, the teacher and politician himself, former minister and former president of Congress made his own the custom of kneading, as in his youth, the bread shared at Christmas with his most close relatives and friends. That gastronomic activity of Master Prieto was always exquisitely celebrated and remembered by the poet Efraín Subero and his wife Argelia de Subero. They delighted in watching him knead the traditional ham bread at his home in San Antonio de Los Altos.

His philosophy on bread is supremely uplifting and admirable. “I come from a mother who made bread. She taught me the meaning and scope of hope through her significant work as a baker. My baker mother taught me to wait. She knew about the seed of the dough, about the yeast, about cooking in an oven and even after the bread was ready, she also knew that the hope of the baker continues. She knew that the true bread, the bread for those who wait, has to be the size of the hunger of the hungry. Today bread is scarce, it is missing in many houses in Venezuela. And that is why there is despair, and that is why some cannot wait and despair. Therefore, we must forge the breath of peace and hope. Therefore, I invite you to keep hope high, so that you do not feel any death impulse that leads to war. I heard him, to the applause of an enthusiastic student crowd, at his opening master class for the Miguel Otero Silva chair at the Universidad de Oriente, Puerto La Cruz, in 1986.

On that occasion, he proclaimed that the struggle for peace is the only thing that can save the world from a catastrophe. “From a nuclear war, no one is going to come back,” she predicted.

Prieto, the teacher, emphasized that making bread and educating were, from an early age, tasks with which he was very familiar. When he had not yet completed high school, he was already alternating his status as a primary school student with the incipient responsibility of assistant teacher, in the first grades of the Francisco Esteban Gómez federal school, in La Asunción. He was a precocious teacher. In the unexpected absence of a teacher, the school director did not hesitate to say, “Look for Luis Beltrán.”

In 1914, when the First World War broke out in Europe, the students of the La Asunción school divided into two camps: one in favor of the French and the other with the Germans. The fights were constant between the two groups. “I commanded the French group,” he once confessed to Alfredo Peña, a journalist from The National.

Prieto was proud to say that those, those of his childhood, were hard days, but very happy. “They woke us up at five in the morning to water the plants. We went to school, and then I had to take care of the domestic animals: the chickens and the donkey”. His—like that of so many young men from Margarita—was a peaceful, sweet, and joyful life. He never lacked coconut, guava and mango. He knew how tasty the ripe mamey is and enjoyed something that the current inhabitants of the capital of Margarita only hear in their memories: bathing, at any time, in the fresh and clean waters of the La Asunción river.

Among his childhood memories, Prieto used to refer to the times when he made traps to hunt rabbits and set up “ties” for pigeons, in the orchards that were so familiar to him in La Asunción, at the beginning of the 20th century. He was born on March 14, 1902. The Margaritan of that time went to bed and got up very early. In the Prieto family, everyone was awake at five in the morning.

It was a hard, peaceful and very happy life, between the morning noise of the birds and the laying hens, the smell of the guava and the fragrance—so deliciously margariteña—of the mamey.

“In my family home, mother and father consecrated to service, I learned that above man is his goodness and that distributing it is a way to increase the spiritual inheritance, because that is the only inheritance that is not diminished when it is shared with others. the rest. I learned it from the lips of my mother, that she kneaded the bread that was the bread for the hunger of the children and when she ate it, the immense hunger of a people who had nothing to eat remained in my mouth… ”. An orator of cultured and easy improvisation, the teacher Prieto said this between memories of his childhood, in a memorable speech, in La Asunción, on October 13, 1968, at the closing of his electoral campaign in which he participated as a presidential candidate.

Leafy greenery and exodus in poetic fertility

In his poetic book wall of my city (1975), Prieto recreates his childhood and youth, the peaceful life of La Asunción and its characters, the hard times of the exodus from Margarita:

Basilia Figueroa/

and Antonia Basilia/

Galito, the helpful/

and Alejandro El Negro, alienated/

they don’t put on picturesque shouting/

but his sayings and memories are preserved/

for the story and anecdote of the day/

In La Asunción, with its leafy patios and laborious daily life, even the shade of a missing tree gives rise to nostalgia:

The same people inhabit/

in the distance that goes /

from the salt mine to the river/

but the landmark is missing/

in front of Juana Micaela’s house/

The jaguar does not exist nor is the mamey /

that gave cool shade/

above the ditch/

There are new houses between/

Mamyoa and her cockfight/

and the house that belonged to Inés Quijada/.

His poetry evokes, with lyrical expression

“….. the border estates/

La Huertica, La Ceiba/

La Noria, Maria Spain/

and even beyond: Roman Medina/

or Loreto Torcat, in Camoruco/

bordering the foot of Matasiete /

where the river collected in a pool /

for the last bath of the afternoon..”/

This great man from Margarita of all time also mentions in his verses

… the industrious and pilgrim people /

that is sown in the earth before death /

or the roads are hustling/

in the solar country of Costa Firme/.

His are the towns by the sea/

the crops of the coast/

in the mountains, on the river bank/

It is the Margarita that —in the exodus— sows towns throughout the entire geography of Venezuela. Prieto himself was part of that legion, which sought —first in Paria, and then in Caracas and the oil fields— the alternative to give channel to the concerns that take hold of those who launch dreams to fly, in search of other horizons.

When an uncle took him at age 16 to work on a coffee and cocoa farm in El Pilar, in Paria, Luis Beltrán Prieto set up his own business, selling starch and oil. But, evidently, he had no other vocation than that of teaching, that of books, and that cocoa and coffee experience was left behind —in 1925— when, sailing on an old sloop, he arrived in La Guaira, from Juangriego, with the firm intention to study at the Liceo Caracas. He was somewhat of an adult when, finally, he was able to enter as a student at the Central University of Venezuela.

At the age of 33, he was in full exercise of his legal profession and was a high school teacher, at the time of the death of the tyrant Juan Vicente Gómez, in 1935.

Luis Beltrán, your minister? What will that government be like?

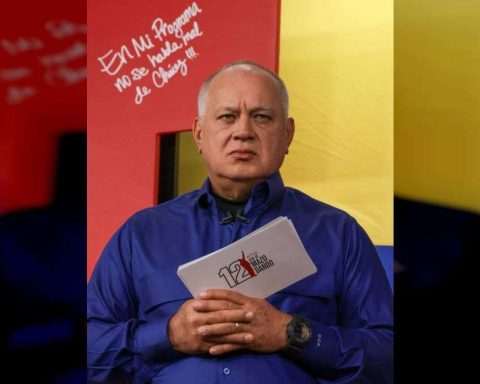

A charismatic politician, a lashing speaker, whose expressions are almost always impregnated with sarcastic and anecdotal humor, Luis Beltrán Prieto Figueroa’s career as one of the great leaders of Democratic Action came to an abrupt end in 1967. Separated from his militancy, after the triumph of his presidential candidacy in primary elections, from the bloody division that this brought about, the People’s Electoral Movement, MEP, emerged with the ear as a symbol and with Prieto as a candidate, in 1968. “I had two brothers, they went to war and died ”, he would always proclaim about his political confrontation and break with Betancourt and Leoni.

Prieto always maintained that at the polling stations AD and URD swindled 200,000 votes from the MEP and curtailed its victory. True or not, the divisive crisis in AD favored Rafael Caldera. The Copei leader was proclaimed president for the period 1969-1974, with just 30,000 votes ahead of Gonzalo Barrios, the official AD candidate.

Throughout his 93 years and until his death in Caracas, Prieto always preached with the example of an austere life, his struggles against corruption and demanded the urgency of a State “capable of understanding that the elevation of man and his social welfare, must be the first concern and that social change cannot be stopped”.

Prieto got fully into politics, starting in 1935. By then he was 33 years old. In Margarita, in the days that followed Gómez’s death, and he said it many times, “we imprisoned the President of the State, General Rafael Falcón, and locked him up in the castle of Santa Rosa.” What would happen next is a well-known story. Prieto Figueroa is part of the founding group of AD. Before, in 1939, he was elected councilor in the Federal District, but President López Contreras maneuvered, with all his power, and annulled the results.

From the partisan fight in the street, he passed to the conspiracy, and Prieto Figueroa became, in 1945, Minister of Education and secretary of the Revolutionary Government Junta presided over by Rómulo Betancourt. The anecdote is very true —and the teacher Prieto, from time to time, recounted it with his Margaritan grace— upon seeing him with the Minister of Public Works, Luis Lander—in an inspection at the La Asunción dam works, Chinta Requena, funny and old neighbor of his family-, reacted with surprise to the investiture that El Orejón had achieved and, in the middle of the street, asked him when greeting him: “Luis Beltrán, are you a minister? And when Prieto said yes, he answered very sarcastically, between laughs: What will that government be like!