By Christian Nielsen

Meeting in Congress in 1884 in Chicago, American workers decided to raise a flag against employers and demand, at least, the eight-hour workday. That was an earthquake that went through a strongly conservative society in its upper strata but boiling in the most vulnerable classes. When employers buckled down in defense of the current status quo, workers responded by declaring strikes across the country.

The US was going through a stage that began at the end of the Civil War in 1865 and lasted until the end of the 19th century. The conquest of the West promoted the construction of the largest railway network on the planet with a massive demand for workers while the cities concentrated gigantic industrial enclaves with the same effect, the employment of low or medium-skilled labor.

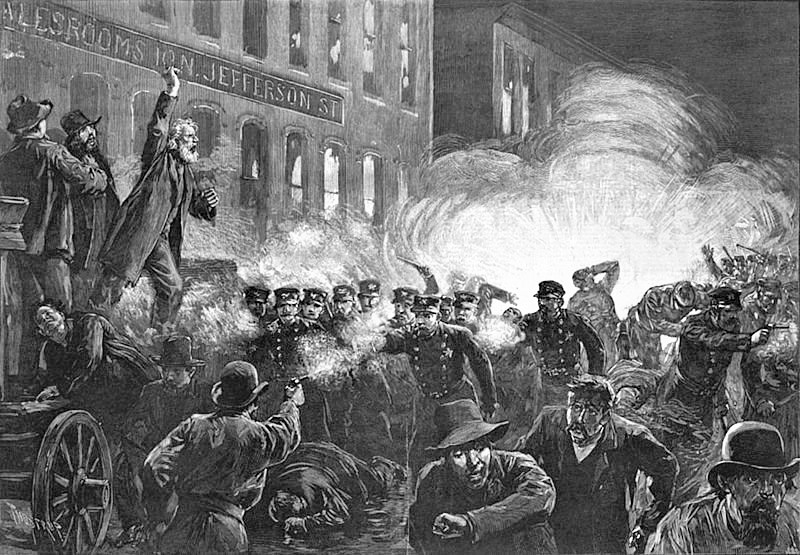

The conflict was inevitable. In Chicago, it occurred on May 3, 1886 as part of the mobilizations that are remembered as the Haymarket Square riot, a protest in front of the McCormick Harvester agricultural machinery factory. There a group of strikers clashed with strikebreakers (scabs) and elements of the fearsome Pinkerton agency hired by the company. The repression was brutal and left six dead and more than fifty wounded.

BOMB, TRIAL AND GANG

The cauldron of violence in Chicago had boiled over. The day after the episode, the mayor of the city authorized, in an attempt to decompress the tension, a public meeting of workers in the industrial nerve center of the city in which refrigerators and sawmills were crowded, paradigms of business opulence. Everything went smoothly when towards the end of the meeting, the police charged for no reason against the concentration of workers from where a bomb that ended the life of an agent was set off.

It was never known if the attack had been moved by the labor leadership or responded to an act of provocation by infiltrators. The establishment reacted with unusual brutality. The organizers of the event were arrested en masse, sent to prison and tried for anarchist practices. The qualification was directed in general against the trade union movement and as an example that the bosses’ reaction was serious, eight of those prosecuted were sentenced to death. Four were hanged and the others confined in prison in inhumane conditions.

The news went around the world and had unforeseen repercussions for both the promoters of trade unionism and its repressors.

FIGHTER AND POET

In those days, the Cuban politician, poet, essayist, journalist and philosopher José Martí -at the time exiled in Zaragoza- made this account of the march to the gallows of four of the Chicago martyrs:

«They are already coming through the passageway of the cells, at the top of which the gallows is raised; in front is the mayor; next to each inmate marches a bracket; Spies walks at a grave pace, his blue eyes slanted, his hair combed back, his forehead magnificent; Fischer follows him, robust and powerful, showing the thriving blood on his neck, the burly limbs enhanced by the shroud. Engel walks behind, in the manner of someone going to a friendly house; shaking off her uncomfortable tunic with her heels. Parsons, as if he were not afraid to die, fierce, determined, closes the procession with a brisk pace. The corridor ends and they set foot in the trap; the hanging ropes, the bristling heads, the four shrouds… A sign, a noise, the trap gives way, the four bodies fall into the air at the same time, spinning and colliding…».

That story that oscillated between the poem and the shudder ended with this lapidary call: “If you don’t fight, at least have the decency to respect those who do.”

LAY PRAYER

Taking his final steps towards the gallows, one of the condemned left this thought: “I do not come to accuse neither that executioner whom they call warden, nor the nation that has been today giving thanks to God in its temples because they have died! hang these men, but the workers of Chicago, who have allowed five of their noblest friends to be murdered!”

And he ended his secular prayer:

“We have lost a battle, unhappy friends, but at last we will see the world ordered according to justice: let us be astute as serpents and harmless as doves!”

This is how the most tragic hours starring the Chicago martyrs were signed, 136 years ago today.