«(…) it is not going to be that some cretin says that one is counterrevolutionary».

(“Rock and roll of Fulanito and Menganito”. Santiago Feliú)

The question that gives title to this work was released, like a fiery dart, by the creators of the magazine Crisisa few days ago, at the launch of number 51 of that historic and resistant Argentine publication on politics and culture.

“Each era has its own demands and the dilemmas are never repeated identically. But when the audacity is lost, only the empire of resignation remains, whose formula can be summed up in four words: it is what it is”, concludes the editorial of the publication and gives way to a series of works where, redundancy is always worth it because in the forward will repeatedly read the word: boldness is the focus.

I felt strongly questioned by all the content of the magazine and, in particular, by that last paragraph of the editorial. Inevitably, it became transferable to the Cuban present.

What would be the audacity today in Cuba not to resign ourselves to “it is what it is”?

I would start by pulling down the skein that covers the island’s own problems like ivy. To do this, we would have to take off our romantic glasses and put on those with a critical and constructive gaze.

This number of Crisis It closes with an interview with Silvio Rodríguez conducted by Mario Santucho and entitled “There is no choice but to be audacious.”

In that conversationreproduced by OnCubathe troubadour points out that for him, “the greatest clumsiness is not to dialogue, to think that without constructive exchange an idea can be created, sustained and defended”.

But there are many clumsy people who, in turn, hold decision-making positions and turn a deaf ear to dialogue. Practitioners of pointing with disdain towards any dissent. They are afraid to sit on the same sofa and face dialogues that are outside the official standard.

And in such a scenario, the officials who do not work end up throwing out the sofa, as in the popular tale. Silvio himself explains it in a couple of verses of his song “Para no botar el sofa (editorial song)”:

“(…)

And, as the mocked spouse,

one morning

throw the least complicated

Through the window.

What little favor to the lights,

what a useless and bitter disguise,

while the forbidden seduces

without having to wear a mask.

(…)»

In keeping with this, I remember some reflections by Eduardo Galeano written in April 2003 regarding the death sentences and subsequent execution of three young Cubans who tried to hijack a speedboat to reach the United States.

“Cuba hurts” is the name of that article. Being honest and bold cost the author of The Open Veins of Latin America gray times in which a pack of bureaucrats, believing themselves owners of the “revolutionometer”; They censored him and even branded him a traitor.

The Uruguayan writer, who maintained and always practiced that “the true friend is the one who criticizes head-on and praises behind the back”, did not tangle his pen in condemning the executions and warned, from his constructive and sincere gaze, that they were “news sad that they hurt a lot, for those of us who believe that the courage of that small country and so capable of greatness is admirable, but we also believe that freedom and justice go together or they do not go together.

He also noted: “The Cuban revolution was born to be different. Subjected to incessant imperial harassment, she survived as she could and not as she wanted. That brave and generous people sacrificed a lot to continue standing in a world full of crouching. But in the hard road that it traveled in so many years, the revolution has been losing the wind of spontaneity and freshness that pushed it from the beginning. I say it with pain. Cuba hurts.“

After that episode Eduardo Galeano took a decade to return to Cuba. He returned in January 2012 and did so because the Casa de las Américas, his beloved and audacious house, was the one who claimed him.

It was gratifying and restorative to see Galeano that afternoon in Havana, reading his unpublished writings in a “Che Guevara” room packed with young people and embracing brothers by trade and life, such as the writers Roberto Fernández Retamar and Eduardo Heras León.

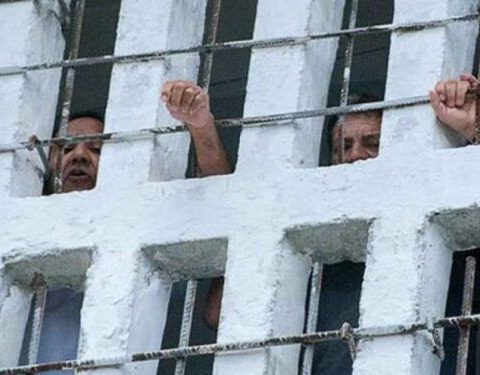

Almost 20 years later, “Cuba hurts” maintains a horrifying validity. Reading it again challenges us in the present tense. Although since then there have been no more executions in Cuba (however, embarrassingly, the death penalty is still in the Penal Code), it is worrying and painful that after the social outbreaks of July 11, 2021 the government will find no other solution than the lesson of sentencing 128 people (mostly young people) and giving 1,916 years in prison in total.

Many other answers are missing to situate audacity in the Cuban present. More than slogans, we need a large amount of audacity to change everything that needs to be changed. And it is urgent.

I once heard from the mouth of a worthy Cuban how unheard of and surreal it was that in a small country without resources like Cuba, vaccines could be manufactured to safeguard against a pandemic but, in the same sense, that same country was not capable of harvesting something as basic as a potato to feed the people.

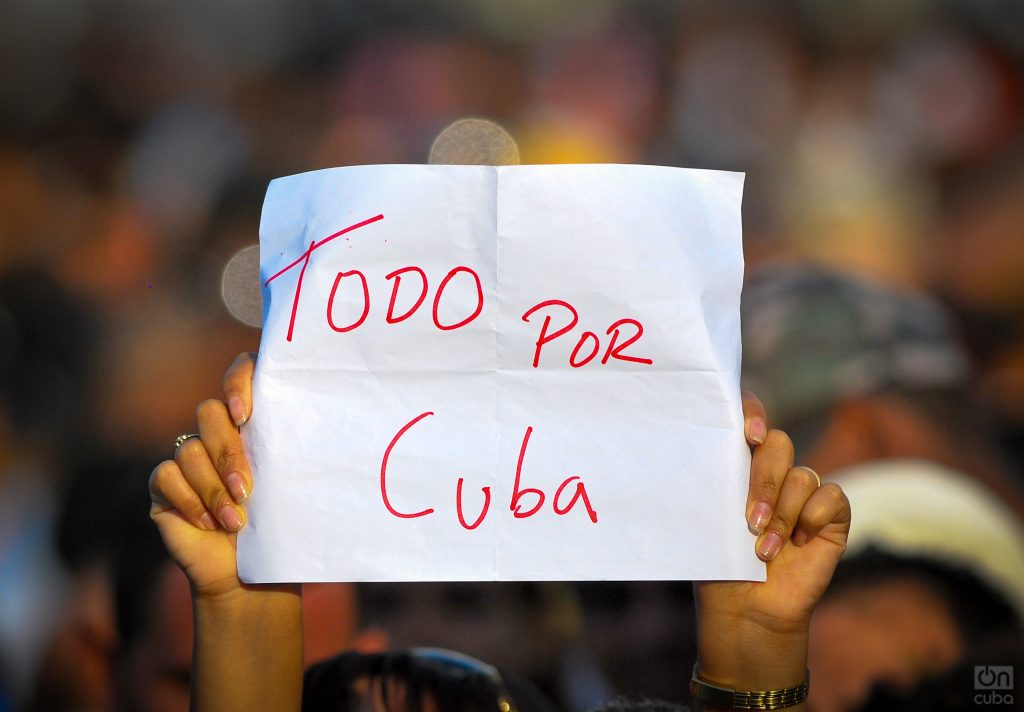

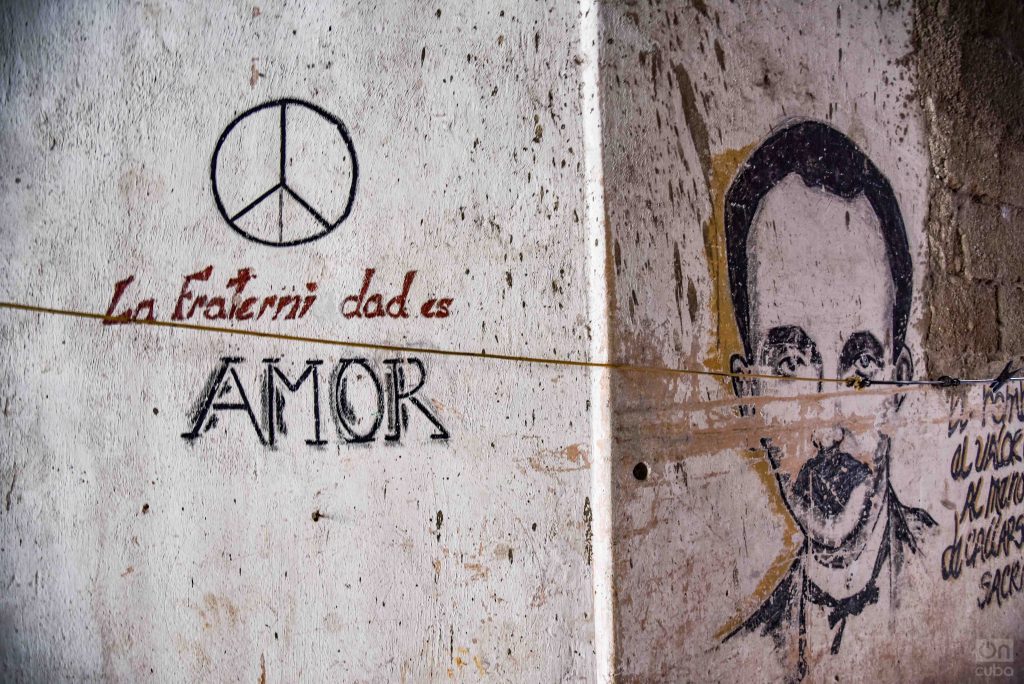

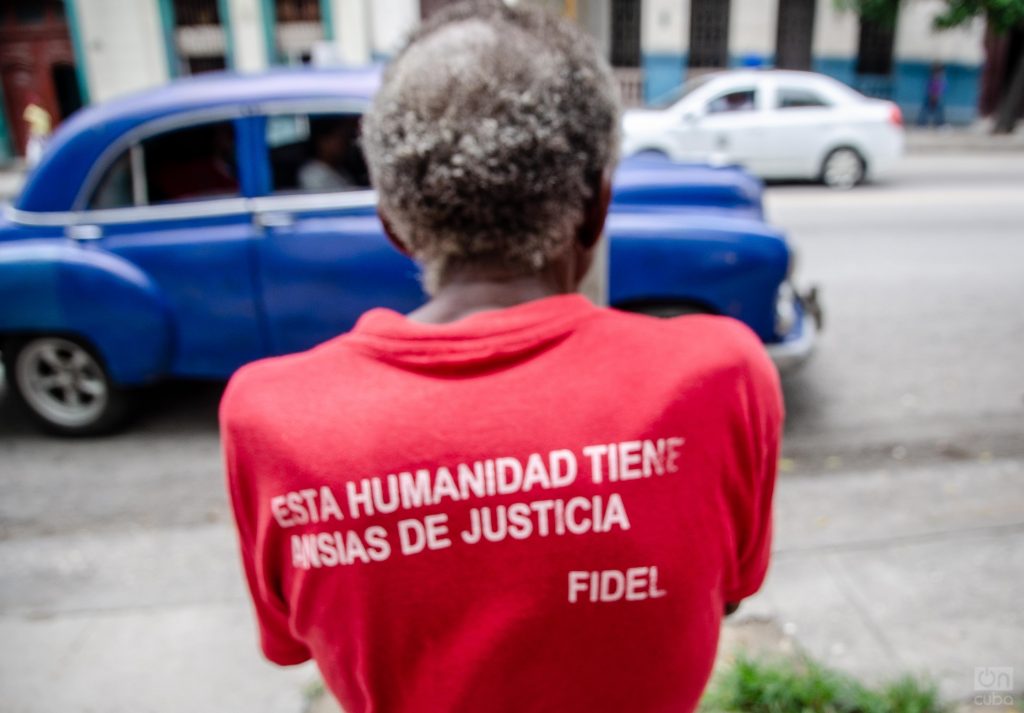

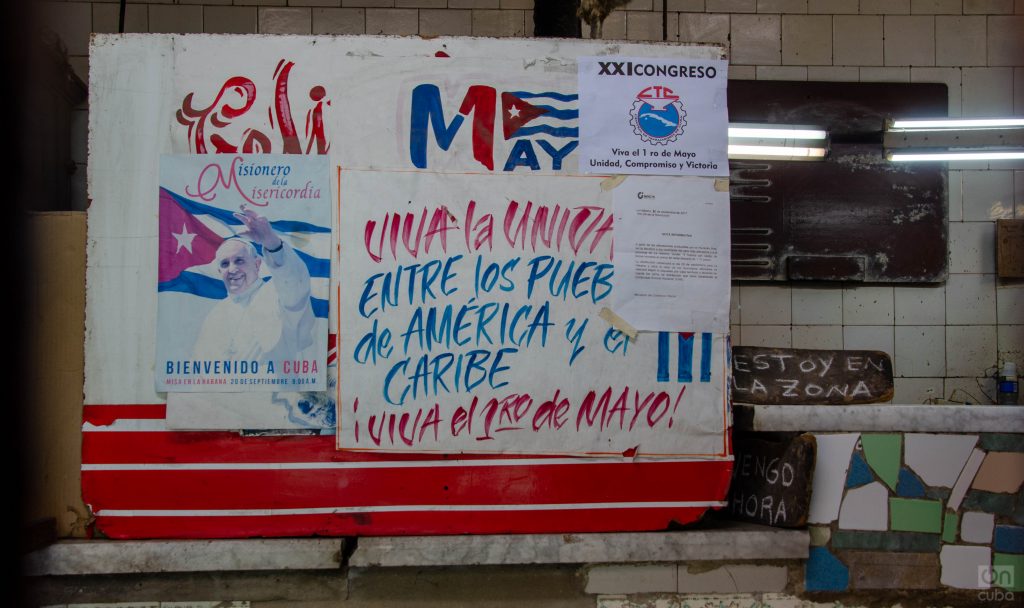

So, I must recognize my compatriots on foot, the ones in these photos, the ones who go out to fight daily and survive, as the first bold ones. On the one hand, the sixty-year-old and crude US blockade and, on the other, the internal blockades and the shortcomings of the Creole rulers to lead the country economically and give legitimate responses to social and political demands accumulated for decades.

Audacity, too, would be to make a homeland against all odds, wherever we are, even if it costs pain and exile. “Sometimes leaving Cuba, unfortunately, makes Cubans more Cuban. But that, unfortunately, is not done here in the country. It only hurts”, an old colleague from the faculty writes to me from Havana, with whom we recently met again through social networks and we were exchanging about the Cuban migratory youth exodus, another of the problems that is hardly talked about in the official press.

That is when what should be natural and healthy in Cuba seems to us to be a daring act: expose our problems, no matter how serious they may be, without fear. Also question old ideas and forms already established. Even discuss and review what has been achieved so as not to cling to the present with empty slogans. In short… quite an audacious exercise.