The day I met photographer Daniel Mordzinski, in 2018, during a sound check for Silvio Rodriguez In a micro stadium in the city of Córdoba, I heard him pronounce a phrase that, over time, I understood as a key to his job. He looked at the newly taken images on the screen and said, almost in a low voice: “I feel like that could be the photo.” There was no euphoria or bombast in his tone. It was, rather, an intimate observation. On another occasion, facing another series, he stated the opposite: “It’s not there. I don’t feel it.”

He said it without emphasis, as if he recognized something that happens on a level that is difficult to translate into words. Over the years—and fortunately for me—we crossed paths again in different settings and shared work, conversations, silences on set. Over and over again I heard him repeat the same idea: to feel or not to feel a photo.

Since then, that elusive certainty has accompanied me: there is a moment in which the photograph seems to announce itself before being closely examined. Beats. It imposes itself as a clear intuition that precedes technical analysis and rigorous editing. As if, before becoming a definitive image, it already knew what it was.

This is not a purely technical matter. Light, framing and experience are essential tools, but they are not enough. The decisive thing happens before: in the conversation, in the shared silence, in that wait that seems unproductive and that, however, prepares the ground. Mordzinski does not limit himself to portraits; establishes a link. Listen. Accompany. He settles into the scene without violating it. His camera does not burst in: it remains. And in that permanence there is a very own ethic.

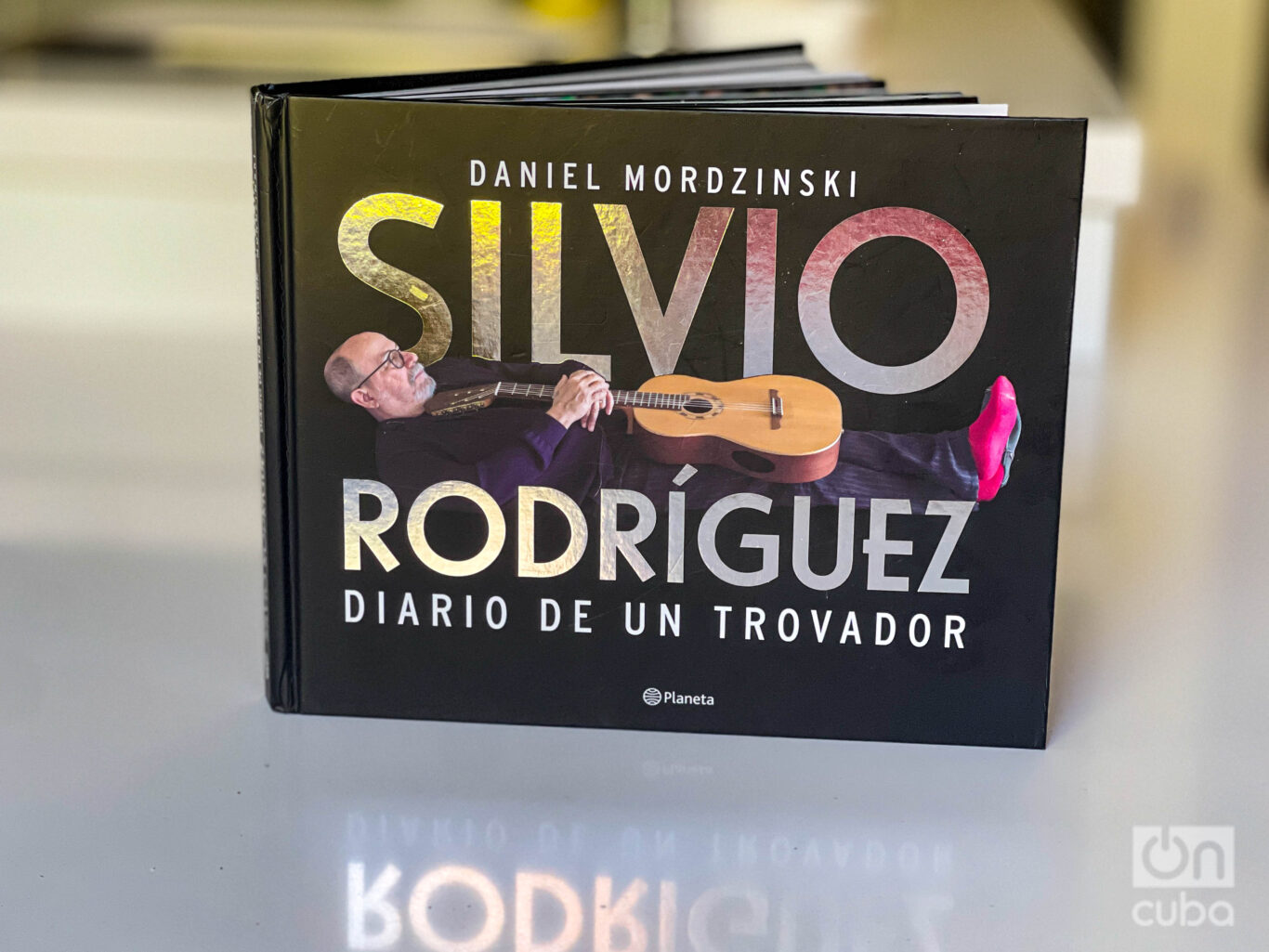

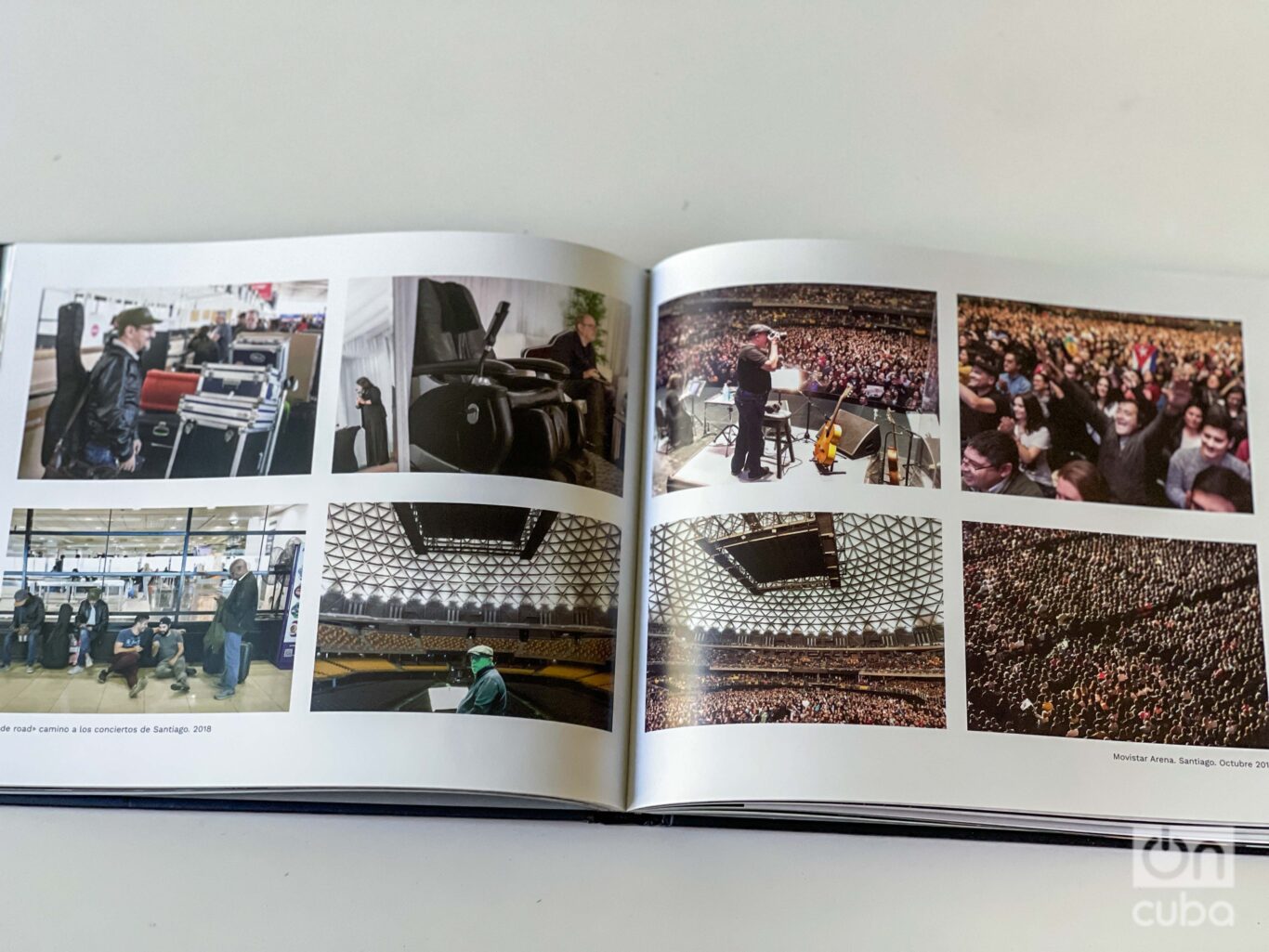

That way of understanding the job runs through his most recent book, Silvio Rodríguez. Diary of a troubadourpublished by Editorial Planeta and presented at the Hay Festival Cartagena 2026 with the participation of Daniel himself; Silvio, virtually from Havana; and the Cuban actor Jorge Perugorría as master of ceremonies. The volume transcends the idea of a simple travel notebook: it is an emotional journey through concerts, cities and meetings that, over the course of a decade, consolidated a relationship.

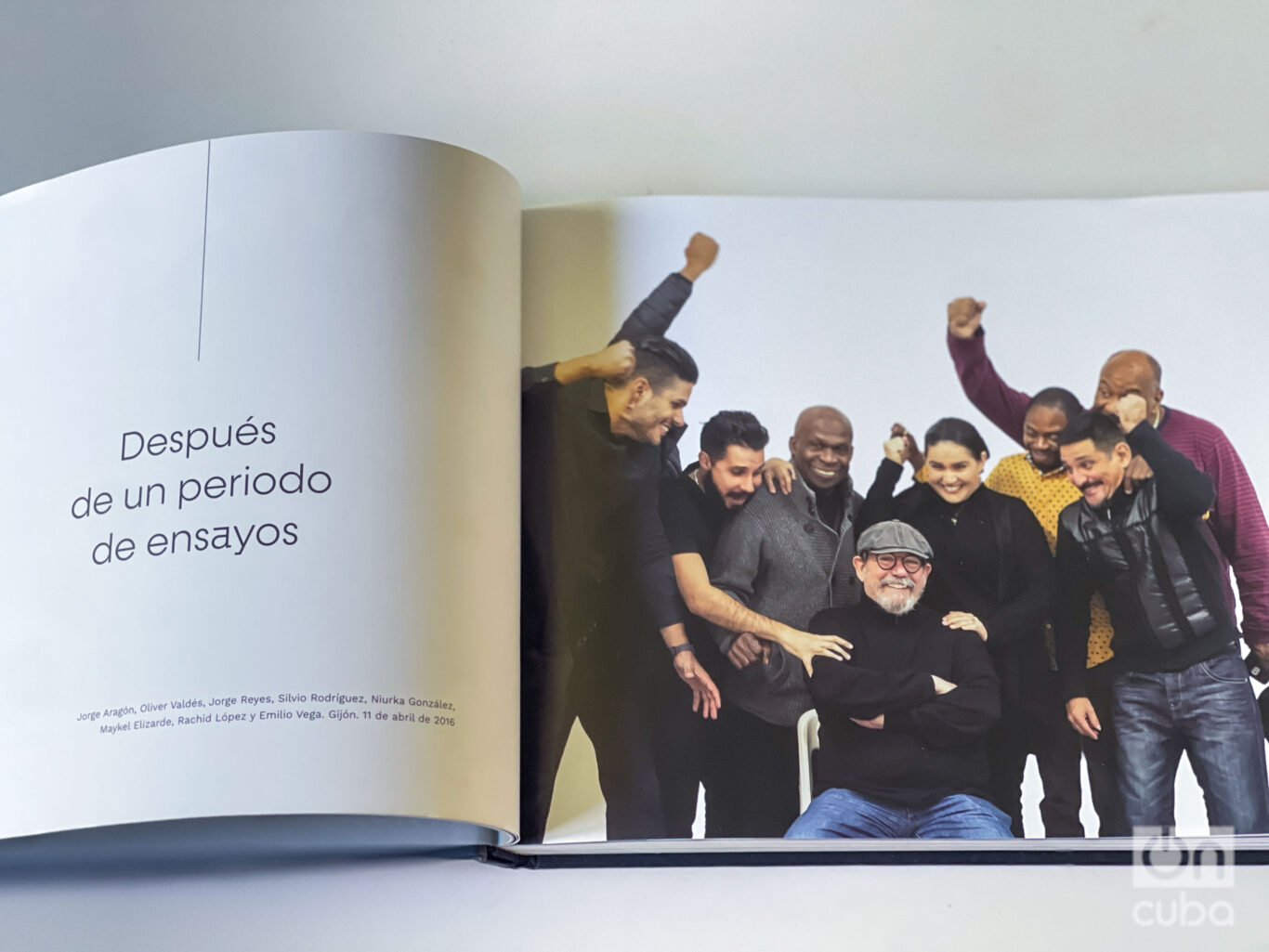

The book was not born from an editorial strategy or a hasty contract, but from the repetition of meetings. This is how Silvio explained it during the talk: it was something that “grew from travel and coincidences”, from that first crossing in the Dominican Republic to the shared tours through Spain, Argentina, Chile, Mexico and other Latin American stations. The troubadour highlighted how these coincidences cemented a bond that ceased to be solely professional and also became personal.

Over time, the accumulation of images began to hint at a shape. Daniel sent photographs after each trip; many, Silvio recalled, were crossed by a complicit humor that portrayed them without solemnity. Until the direct proposal came: “One day Daniel told me that he wanted us to make a book.” And he finished with irony: if a photographer like him proposes something like that to you, “you have to be stupid to say no.”

From Mordzinski’s side, the approach had a narrative character from the beginning. He confessed that he grew up listening to Silvio and that he always considered his songbooks as true collections of poems, because in each song lives an autonomous piece of poetry. Accompanying him in concerts, in family intimacy and in dialogues with other creators allowed him to understand that each portrait was just a fragment of a larger story. “Every photograph contains a story,” he explained. Above all, he is interested in that invisible territory that surrounds the image: what happens before and after the click, when life is still flowing and memory begins to take shape.

To talk about Daniel Mordzinski (Buenos Aires, 1960) is to talk about a patience turned into an archive. For more than four decades he has woven, almost without fanfare, the most complete visual map of literature in Spanish. They call him—justly, although the label is insufficient—the “writers’ photographer.”

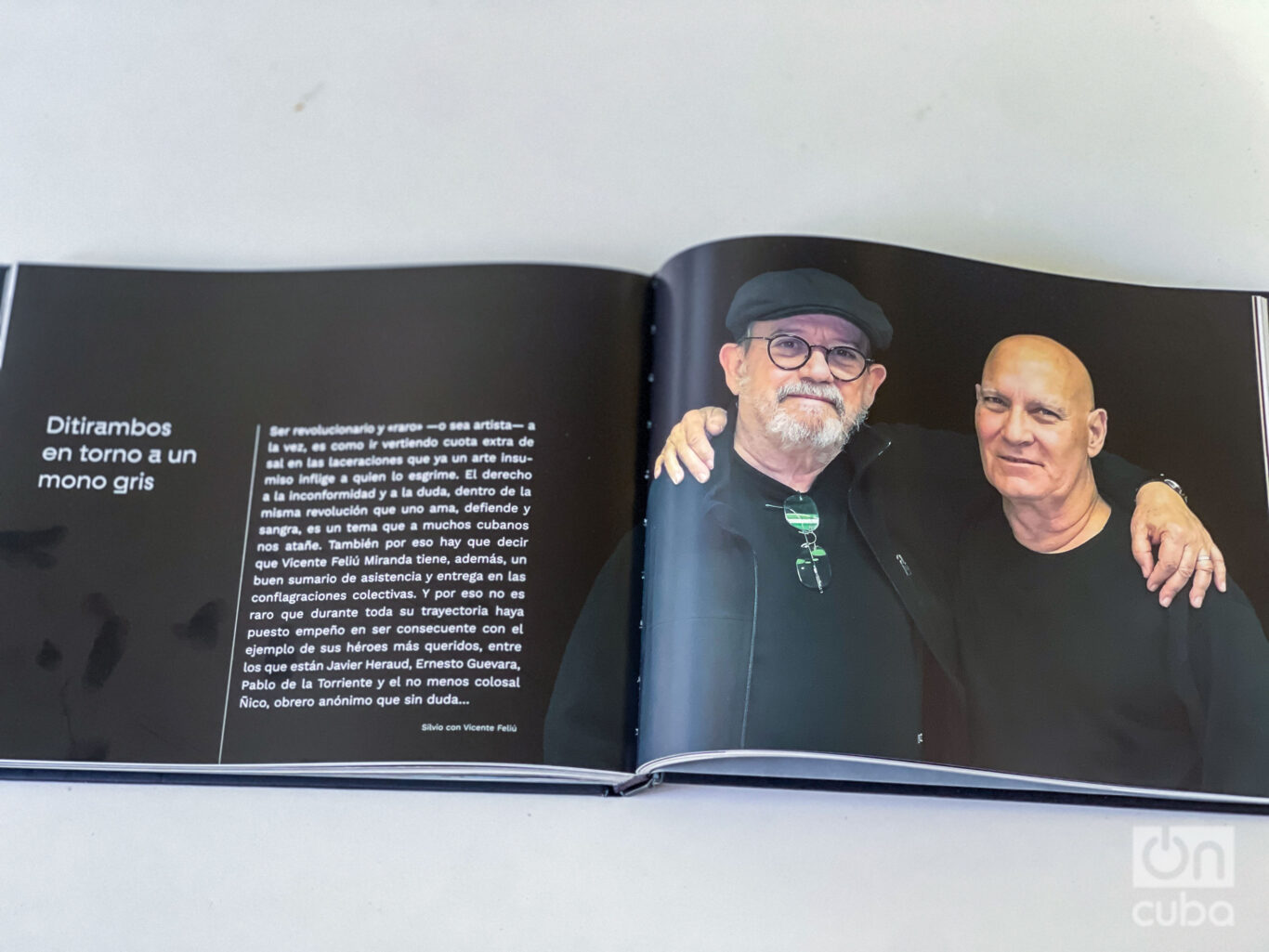

Major figures such as Jorge Luis Borges, Gabriel García Márquez and Mario Vargas Llosa have passed through his lens, but also emerging voices who, thanks to his gaze, found a first portrait at the level of their work. More than accumulating faces, Mordzinski has built an affective memory of Ibero-American culture, where each image is the result of a bond and each shot, the synthesis of an encounter.

When Daniel states “I feel like that is the photo,” the verb is not coincidental. Before looking, perceive. Detects the moment in which the public figure withdraws and the person appears. He knows that the truth rarely coincides with the most spectacular gesture; It usually resides in a minimal gesture, in a distracted look, in a breathing that loosens. That moment is fragile and brief. It requires patience.

In their approach there is an explicit desire not to invade. It does not seek to impose a pose or create a scene. Observe, adjust the essentials and wait. This economy does not respond only to technique, but to respect. He does not shoot out of anxiety or accumulation: he photographs when he perceives that something genuine is happening. This contention is, at its core, a moral stance.

I confess something behind the scenes of this book.

Among the many things I admired about Daniel Mordzinski—being at his side, gladly holding the endless black canvas, putting together an improvised set in the most unlikely places for a portrait painter—there was a silent lesson that I understood over time: Daniel does not waste his bullets. I say better: he doesn’t waste his shots. He doesn’t photograph because of anxiety. Wait. Observe. It moves just enough. And when you feel that “the photo could be there”, then yes: that’s where it happens. That economy is not technical: it is ethical. It is a way of relating to others. Not to invade. Don’t overwhelm the moment. That’s where, I think, that “feeling” he talks about comes from. It is not magical intuition; It is sustained attention.

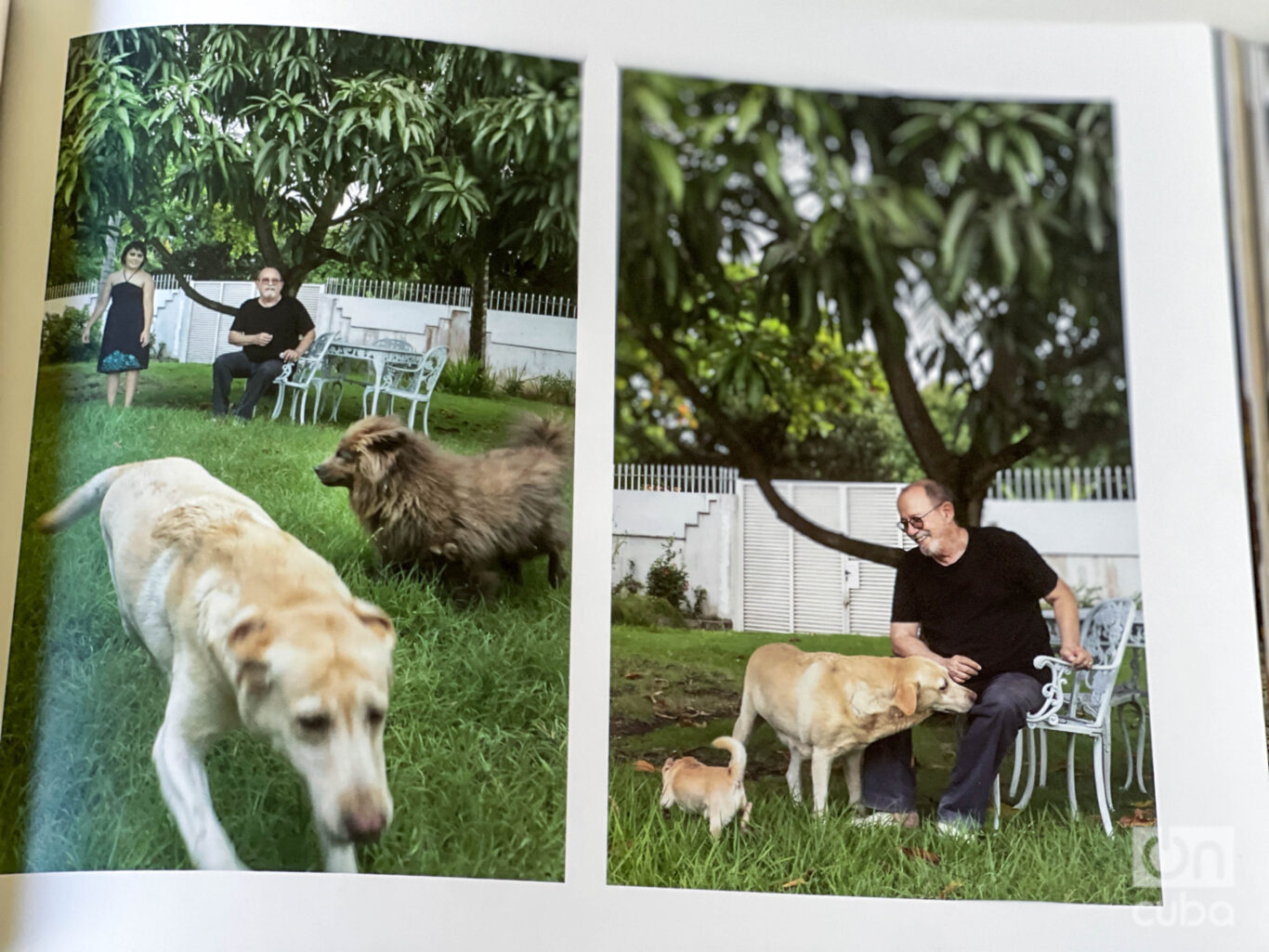

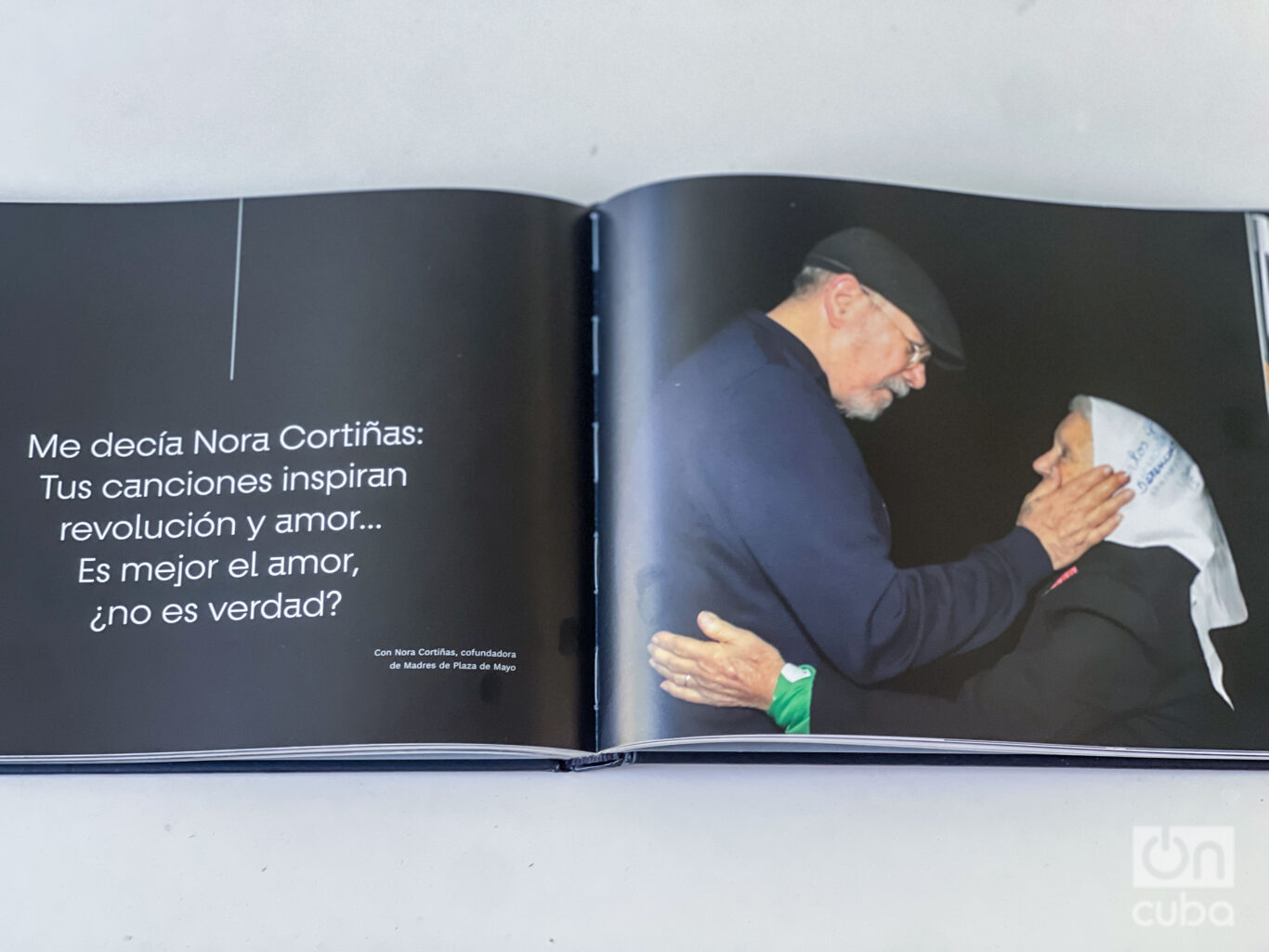

And then there is the person portrayed in this book: Silvio Rodríguez. Little given to photos. Rather introverted, simple, humble to the bone. He is not one of those who surrender easily to the lens. His territory is the song, behind a guitar or a camera, not in the pose. But when he commits, he delivers. And with Daniel something relaxes: the gesture relaxes, the guard drops, a more authentic breathing appears. Why does Daniel achieve it? Because he is not in search of the icon, but of the human being. Because it does not impose itself on the character. Because he knows how to wait for the moment when the troubadour stops being a public figure and becomes a man again. And that, in someone like Silvio, is no small feat.

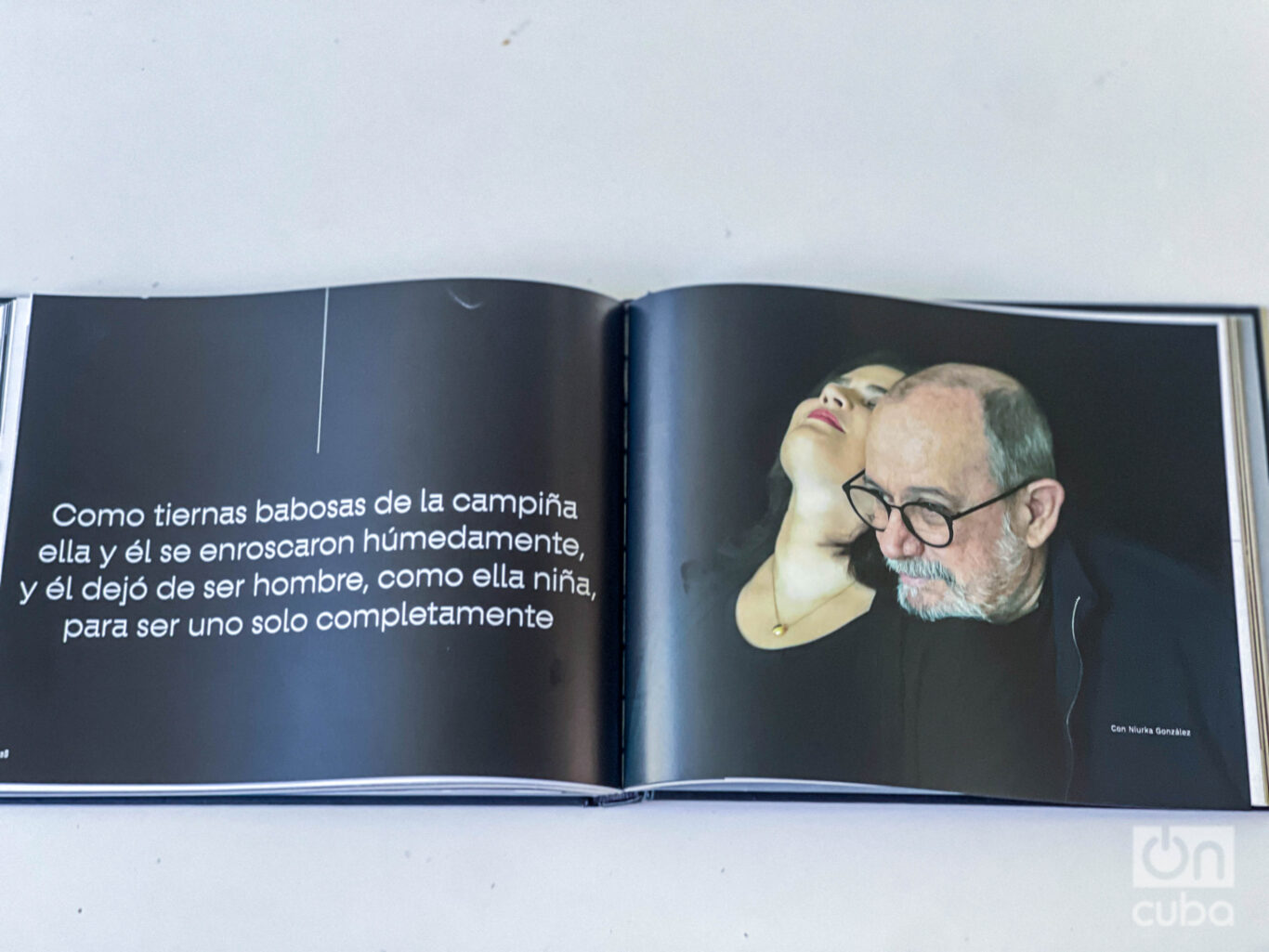

But there are also accomplices in those photos that now make up this book. Invisible accomplices that sustain the climate. I think of Niurka González. I am a witness that, just as she is virtuoso with the flute, she is virtuoso as an ally. Every time Daniel came up with a photo, every time he proposed a “crazy” beautiful frame or asked for one more gesture, Niurka was that other leg of the table that proposed the right moment. A decisive complicity.

Because great photographs are rarely a solitary act. Although the shot is fired by a single person, around there is a network of gestures, silences and complicities that make it possible. In Silvio Rodríguez. Diary of a troubadour it is felt: they are not torn images; They are granted images. And maybe that’s the key. Photos, then, are not only made: they are woven.

In this book, furthermore, the word occupies a central place. Silvio contributes fragments from diaries, comments on the photographs and verses that dialogue with the images. The commonplace that “a picture is worth a thousand words” does not apply here: text and photography complement each other until they form a unit. The feeling Daniel invokes is not a mystical intuition, but the result of sustained attention.

In the prologue, Silvio himself remembers a chance meeting in Paris and thanks Daniel with words that reveal more than just professional admiration: they speak of mutual admiration. That link explains why the images do not seem torn, but granted. There is no assault or forced capture, but rather tacit consent.

After going through the book, the opening phrase takes on another meaning. The photo “is” or “is not” depending on the quality of the relationship that precedes it. The camera is just the instrument; the decisive thing happens in the human exchange. The feeling Mordzinski speaks of is not an inexplicable outburst: it is the consequence of having been truly present.

The question, then, stops being how to create an image with emotion and becomes something simpler—and, at the same time, more complex—: how to position oneself in front of the other. Daniel seems to have found his answer in patience, humility and an attention that turns the job into a way of life. There is, without a doubt, a “Mordzinski feeling”, in the same way that there is a decisive Cartier-Bresson moment: an exact and unrepeatable point in which the image is not only composed, but felt. Silvio Rodríguez. Diary of a troubadour is eloquent proof of that certainty.