Locked in the dark while the batteries run out and the candles melt, patience digesting, who could be interested in the decision of the manager of a baseball team? How important is the name of the champion of a League (I like to continue calling it the National Series) where the numbers fall off the uniforms like expired stickers, the referees forget the counts and the players, so many times, behave like apprentices?

They are the questions of pragmatic thinking, those dictated by common sense in times of crisis and survival.

There is no fuel for buses, nor for electricity generation nor for irrigation in crops. The prices of services rise, the price of the dollar in the informal market and in banks reaches scandalous figures for the modest worker. Schools adjust their schedules. We go outside to get some air, we look at the sky and see the clouds moving over a country at a pause. Is there time to think about a game, about the development of a championship for boys who no longer dream of “making the Cuba team,” but rather of playing in foreign leagues?

Living in the uncertainty of tomorrow is a lonely experience, because the answers are nowhere to be found, and although others carry the same doubts, they all weigh too much to share.

In those “hardly human” years of the Special Period, I was a child from there, on San Rafael Street in Matanzas. Sitting at the door in the middle of the blackout, I could see the lights on of the baseball stadium where the Henequeneros team was champion in 1991. Those white lamps on the immense towers stood out on the outskirts of a silent and dark city. Only at times could you hear the echo of the hubbub over the home run of some Matanzas native or surely an important strikeout.

Sometimes, with my grandmother, I would wait for those lights in the distance to go out so that, with luck, the lights at home would come on.

In those 90s there was no fuel or food either. My maternal grandfather traveled with his driver’s license on the only two buses a week that passed near the central where he lived, to bring me milk, a little meat and sugar cane.

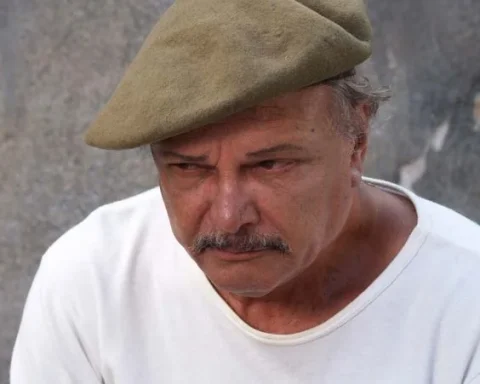

My paternal grandfather “solved” food with friends from work. It was he who took me to the stadium for the first time. I can’t know if he had any hope in those years, I can’t know about his silent pain. In childhood one perceives other things because good adults hide sadness and frustration, so that we children live as if in paradise.

But one thing is for sure, my grandfather had the passion left: he had rum, dominoes and baseball.

Even when Henequeneros disappeared and became the defeated Matanzas, the stadium was still lit at night so that, for three or four hours, people like my grandfather could also play at being children; They had the right to scream with euphoria or rage, and they would forget the ruthless reality when their team, miraculously, won the game.

I inherited the passion from my grandfather and today I take my children to the stadium to feel the adrenaline of jumping in a group with a hit or a field. They laugh out loud, although they do not understand why the conga is playing now, nor why the others are applauding. They observe those who dance, the man dressed as a lion or a crocodile who raises his arms and “walks strangely.”

My daughter’s eyes are wide open, she moves her head from side to side, she gets close to my ear and shouts, “Dad, everyone is happy here!”

I should explain, but I want to be a good adult. I give her a kiss and get up to jump with her, and I don’t care if Matanzas loses or wins.

We still have baseball, even though they no longer light up the fields at night, and the “grand final” is played in a “neutral stadium” and other grandparents cannot see their favorite team live, save batteries to listen to the games on the radio, because they don’t have electricity for television either.

We still have dominoes, rum, some festivals for jazz, trova and cinema. We still have to save our strength so that the children do not discover that this paradise does not exist.