The US Government would be considering sending “small amounts of fuel” to Cuba, despite the current oil fence tax on the island from Washington.

This was revealed by sources familiar with the british magazine The Economistaccording to which these shipments would not be crude oil, but “gas for cooking and diesel to maintain the water infrastructure”, thus alleviating the current energy crisis in the Caribbean country would be minimal.

Even so, if these shipments materialize—and are accepted by Havana—they would be a palliative to the critical social situation on the island after years of economic decline now aggravated by the pressure of the US Government on Cuba after the attack on Venezuela and the capture of Nicolás Maduro.

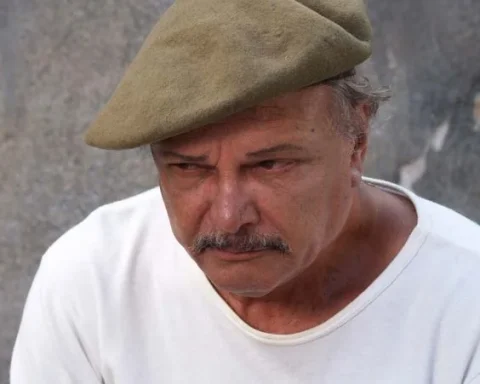

The Economist focuses his article on the role of the secretary of state Marco Rubio in the Cuban crisis and highlights the crossroads that the Cuban-American politician, historically in favor of a hard-line policy against Havana, could face.

If the current measures of the Trump Administration—such as the threat of tariffs on countries that supply fuel to Cuba— do not entail the change desired by Washington, “Rubio will be subjected to enormous pressure (from the most radical sectors) to adopt a more aggressive stance. But this could be counterproductive,” says the publication.

According to the British media, from the outset the White House “does not seem willing to go that far” and, if greater pressure measures are applied, “an induced humanitarian crisis could occur along with another wave of Cuban ‘rafters’.” In that case, the Secretary of State could become the most visible face of that crisis, which could have a political cost among the MAGA base.

Experts such as Jorge Piñón, from the Energy Institute of the University of Texas, affirm that Cuba’s energy situation is critical and that if by March the country has not received fuel “it will have reached zero hour”, with the economic and social implications that this would have.

Cuba on the verge of “zero hour”: International expert warns of possible energy collapse

Economy as key

The Economist highlights that Cuba does not have the attractive resources for the Trump Administration that Venezuela does and remembers that, unlike what happened in Caracas, Marco Rubio himself has told the US Senate that, although his Government would love to “see a change of regime” on the island, “That doesn’t mean we’re going to do a change.”

Their bet so far is that the crisis and fuel shortage will lead Havana to negotiate, something that for the moment the Cuban Government denies has happened, while at the same time it has drawn the maintenance of the socialist system as a red line for a possible negotiation.

Given this position, Washington seems to be trying a change of tone. This weekend, during an interview with BloombergRubio himself pointed to economic opening as “a possible way to move forward” amid the growing tensions between both countries.

“I think that, without a doubt, your willingness to begin to open up in this sense is a possible way forward,” assured when asked if there was any type of solution for the Cuban Government in the midst of the current oil siege, while emphasizing that “Cuba’s fundamental problem is that it does not have an economy.”

Marco Rubio on Cuba: “Opening” the economy is “a possible way to move forward”

The Cuban-American politician avoided mentioning the impact of US sanctions on the island and attacked the Cuban authorities, whom he said “do not know how to get out of this situation” and whom he accused of wanting to “control everything” and not giving citizens participation.

“They would rather be in charge of the country than allow it to prosper,” he said.

At the same time, Rubio recalled that the US has been providing humanitarian aid “directly” to the Cuban population, specifically to the victims of Hurricane Melissa, through the Catholic Church, and that his Government recently announced an increase in that assistance, a decision that Havana described as “hypocritical” in the midst of the current US pressure against the island.

“That is something that we are willing to continue exploring, but obviously it is not a long-term solution to the island’s problems,” he said.